“For behold, Thou hast loved truth; the hidden and secret things of They wisdom hast Thou made manifest unto me. Though shalt sprinkle me with hyssop, and I shall be made clean; Though shalt wash me, and I shall be made whiter than snow.” – Psalm 50

Surviving institutionalized child abuse can sometimes have life-long ramifications. Because not only were you brutalized by an individual, but by an entire organization that covered-up and enabled your abuser. This makes forgiveness a difficult process. Since, not only do you have to forgive the individual who molested you, but a system which facilitated it. However, I in no way want to diminish the abuse suffered by those who were harmed by someone outside of an organization. Because, oftentimes, especially within families, there also persists a network of silence and denial. Yet, the idea of “the family” can endure despite the evil perpetrated by certain actors. For instance, the benefits of fatherhood will rise above the worst examples. I have seen men, who came from highly dysfunctional families with abusive, neglectful, or absent fathers, rise above their childhood circumstances, to become truly loving fathers themselves. The same cannot be said about the Roman Catholic Church.

In terms of Roman Catholicism, I have often stated: “I can forgive that priest, but how do I forgive a thing?” In other words, how do I forgive the Catholic Church? Is that even possible?

My history of abuse in the Catholic Church preoccupied most of my life. For a long time, I wondered if I had brought it upon myself. Because it kept happening. Starting at age 11. Then again when I was 16 years-old. Afterwards, into my 20s, I was still being abused. Subsequently, I undoubtedly believed that I had asked for it. But, the rate of revictimization amongst survivors of childhood sexual abuse remains very high. What went wrong; and how could I even begin to heal?

The first step is just actually accepting the reality that you were abused. This might seem odd, but due to the fact that grooming, manipulation, and even brainwashing is used to abuse children – oftentimes, there are survivors who never realize that they were abused. A classic, and albeit infamous example is a public revelation made by the actor George Takei who rather nonchalantly related how as a minor he was sexually assaulted by a man when he was in the Boy Scouts. This sort of denial is endemic in the LGBT community, but amongst others – it can take the form of dissociation which may result in traumatic memories being repressed. In my own life, for many years, I never considered the abuse I experienced as a child and teenager was actual abuse. When I was a boy, I think this was a subconscious avoidance strategy. As an adult, the trauma-bonding between gay men is pervasive. The shared stories of gay men’s earliest sexual encounters (oftentimes with older men) are framed within the false context of mentorship. This sick conviction is coalesced in gay culture with the omnipresent image of the benevolent but sexually domineering “daddy.” Then, in a vain attempt to heal their trauma, a large number of gay men reenact the abuse. I did that for over 10 years. It did not help. Instead, I was further traumatized.

“Our cross is vain and barren, no matter how heavy it may be, if it is not transformed into the Cross of Christ by our following Christ.” — St. Ignatius Brianchaninov

The second step is bringing those pains, injuries, and sorrows to Foot of the Cross. To not do so, is to wallow in your own excrement. Imagine the scene portrayed in Christ’s most powerful parable – the “prodigal son” reduced in his wretchedness to sleeping in a swine-yard; while coveting their leftover slop. I have been there – literally and fugitively. And it is a very dark space of total desolation. Because this is not just suffering without meaning, but misery without an endpoint. Such anguish will often culminate in self-destruction and suicide. I found that out the hard way. As a child, I stupidly thought that I if I could finally do what I wanted, be who I wanted to be, and live around those who shared my ideas, I’d finally find true happiness and freedom. I didn’t. In his greatest work, “The Brothers Karamazov,” Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote: “The world has proclaimed the reign of freedom, especially of late, but what do we see in this freedom of theirs? Nothing but slavery and self-destruction!”

I was born in 1969. Two years after the Summer of Love in San Francisco. A couple of months before the massive love-in at Woodstock and the Stonewall Riots. The “sexual revolution” of the 1960s would spawn the gay liberation movement of the 1970s and the social acceptance of pornography. The 70s also saw the pop-culture approbation of child sexual exploitation and pedophilia; see Jodie Foster in Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver;” Brooke Shields in Louis Malle’s “Pretty Baby;” and Björn Andresen in Luchino Visconti’s “Death in Venice.” I bought into the lie. That I could reimagine myself, my body, and the entire world to conform to my own conceptions and beliefs. For my generation, and for the one which proceeded it, this experiment was a resounding failure. Our denial of nature, when we thought that our anus could be utilized like a vagina – resulted in the brutal carnage of AIDS. Our bodies literally began to decompose while we were still alive. The eventual extinction of the gay male community was only halted by the advancement of pharmaceutical science – which resulted in a promulgation of life, but also an enslavement to a daily regime of artificial preventative therapeutics. Not only to lessen the viral load in those who were already HIV-positive, but in the form of a pre-exposure prophylaxis, like PrEP.

In the end, sexual liberation resulted in subjugation and death. Yet, at first, even though our foolish dreams seemed more distant than ever, and everything goes wrong, true adherents (inspired by their desperation) tend to double-down rather than reassess their earlier aspirations. I did. Saint Philaret of Moscow accurately described this mindset:

“People who have allowed themselves to come into slavery to sins, passions, and defilements more often than others appear as zealots of external freedom, wanting to broaden the laws as much as possible. But such a man uses external freedom only to more severely burden himself with inner slavery.”

In the midst of my own implosion, everyone around me became heavily involved in LGBT political advocacy and activism. In the 1990s, that included a push for gays in the military, the recognition of same-sex civil partnerships – and in San Francisco and Berkeley – the toleration for nudity in public, as well as the legalization of recreational drugs. At the time, the most phenomenally popular film was “Titanic.” A genuinely frightening scene in the movie, that really stuck with me, followed the life-jacket wearing Rose’s drop into the frigid Atlantic Ocean following the sinking of the great ocean liner. Almost immediately, a drowning man grabs a hold of Rose in order to keep himself afloat; almost killing her to save his own life; though he would have died eventually of hypothermia. I was constantly getting pulled under. In Christopher Marlow’s play “The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus” the demon Mephastophilis says: “It is a comfort to the unfortunate to have had companions in woe.” And, as I found out, in death. In 1993, Randy Shilts’ landmark book that detailed the early years of the AIDS crisis made it to the small-screen; a pivotal event in the movie version was a San Francisco city council meeting during which the possible closing of the gay bath-houses was discussed. An actor portraying the pioneering AIDS activist Bobbie Campbell gave a poignant albeit irrational speech in favor of not closing the bath-houses; he finished by stating: “I would rather die as a human being than continue living as a freak.” When I first heard these lines, I thought they were courageous and noble. A few years later, after I fell face-down into the gutter – chocking on my blood, while trying to stand back up – only to slip on my own excrement. There was nothing noble about this. Nor the grisly and excruciating deaths endured by blotched-covered 20-something year-olds. They did not die as martyrs to some lofty cause. It reminds me of a line from “Crime and Punishment:” “Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.”

Though, for the longest time, I didn’t see things that way. I blamed gay man. All of them. I was filled with loathing. So all-encompassing was my hatred that I could not return to San Francisco without becoming physically ill. I held on to this hatred until I started to explore my own past abuse and trauma. Then, I discovered what had been hidden to me, although the truth was always in plain sight; that the majority of gay men were sexually abused as children. When we were together, we oftentimes talked about the past, but no one could see it. Knowing this, doesn’t excuse bad behavior (theirs or mine). However, it helps to explain much. Many of us were victims. In my case, I realized that my downward slide towards oblivion began in school lavatory where a priest raped me. Knowing that. caused even more hate to replace the anger I may have just dispelled.

“In truth there is only one freedom – the holy freedom of Christ, whereby He freed us from sin, from evil, from the devil. It binds us to God. All other freedoms are illusory, false, that is to say, they are all, in fact, slavery.” – St. Justin Popovich

The third and most important step is forgiveness. When I was younger, I was a slave to my vices – most of them sexual. When I got older, due to age, apathy, and increasingly poor health, the temptations of the flesh was something that belonged almost exclusively to the past. Only, hate and anger became my new passions. Over a matter of a decade, I moved from rage to rage. Following a rather intensive therapeutic exploration of my childhood abuse in the Catholic Church, and subsequent re-victimization in the gay male community, I began to treat and heal a few of those wounds. Yet, my return to the Roman Catholic Church did not provide me with balm, but carbolic acid. First of all, I was looking for practical guidance on the topic of same-sex attraction; I’d previously read “The Catechism of the Catholic Church,” and its pronouncements on the matter were unambiguous. But as I soon discovered, there was a massive chasm between official “Church” teaching and the pastoral practices established at the local parishes. I wasn’t particularly shocked. During the 1990s, I attended same-sex “Catholic” wedding ceremonies held in streamer-filled San Francisco backyards, officiated by an openly gay Catholic priest. Naively, I thought such liberal experiments were endemic to the gay enclave of San Francisco. Back then, I spoke to a priest about why he participated in such weddings. At the height of the AIDS crisis, he believed that encouraging gay males to be monogamous was their only hope; he said: “I’d rather marry them, than bury them.” But their gamble with other people’s lives flopped. In the coming years, studies would show that the majority of so-called monogamous partnerships were actually open relationships, and most gay men were becoming HIV-positive through their main partner. When I reentered the Church, these priests with blood-on-their-hands were still there. And they hadn’t changed. One of them told to go find a boyfriend. Eventually, I did though find some “good” priests who did not subscribe to such evil. However, to locate them, I had to be re-traumatized. This caused a strong recurrence of mental illness that almost cost me my life. It wasn’t worth it. Because even these good and faithful priests existed under a constant shroud of fear and hesitation. Homosexuality was a controversial subject in the Catholic Church. Too many priests (and bishops) were themselves gay. The reasons for this are far-reaching and somewhat complicated; I cannot recommend enough Dyan Elliott’s excellent book “The Corrupter of Boys: Sodomy, Scandal, and the Medieval Clergy.” In a gross overs-simplification of her thesis, I think she proves that widespread homosexuality and boy sex abuse in the Catholic Church clergy is a feature, not a bug.

At first, from this reality, I fled from it. I bought into an invention; that homosexuality and pedophilia were aberrations introduced into the Catholic Church primarily following the innovations of the Second Vatican Council. Supposedly, the realm of the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) was a stronghold against the debauchery and decadence that infiltrated the liberal Church. For the most part, the adherents of this theory focused on the liturgical division within the Church between the TLM and the Novus Ordo or the “New Mass” which was promulgated by Pope Paul VI in the 1960s. Less than a year after coming back to the Church, I moved across the country to live near a religious order of TLM priests. I thought, away from California and the progressive-wing of the Catholic Church, I’d be safe. I wasn’t. And neither was anyone else.

The conspiracy of silence which protected and enabled priests everywhere in the Catholic Church was intensified in the TLM community. Many of those Catholics who were its followers, like myself, and been troubled and disappointed in the so-called Novus Ordo Church. For many of them, the TLM was their last hope. And they wanted to protect it. And the priests who celebrated the Mass. This goes part and parcel with a general trend in Roman Catholicism which separated the clergy from the laity – primarily through forced celibacy – and set them apart as a higher form of human-being; hence, in Catholic theology the priest is viewed as “In persona Christi.” This is reflected in all of their liturgies. In the Novus Ordo – the priest continuously faces the congregation – he is the star; hence, the rise of the celebrity Catholic priest. But even in the TLM, the priest is at the center of everything. In Orthodoxy, during the prayer before the Great Entrance, the priest prays: “For Thou art the Offerer and the Offered, the Receiver and the Received, O Christ our God….” This idea is noticeably lost in Catholicism. At the TLM, following the Mass, conversations between the laity sometimes examined the outward piety of the priest; i.e. the length of time he elevated the host; the manner in which he genuflects; or the way he holds the chalice. This sort of priest fandom was often female-centered and reminded me of cloying mothers who fawn over their anxious sons. In Orthodoxy, the priest is comparatively protected by the iconostasis from becoming a showman. Concerning the iconostasis, Leonid Ouspensky wrote: “Although, on the one hand, it is a screen dividing the Divine world from the human world, the iconostasis at the same time unites the two worlds into one whole in an image which reflects a state of the universe where all separation is overcome, where there is achieved a reconciliation between God and the creature, and within the creature itself.” I never observed any such union in Catholicism.

While I understand the need for hierarchy and the corresponding decorum which often goes along with such formal structures, the Catholic Church cultivates an indifference and arrogance which is distilled within the distant countenance of many of their bishops. I once sat across from the “princes of the Church.” Begging them to protect the vulnerable and comfort and support those who were already abused. There is a sociopathic stare that is evident in serial killers; see Norman Bates at the end of “Psycho.” The Catholic hierarchy has this. They could not offer solace; not even a kind word. After many such meetings, they had nothing to say. When I first spoke to an Orthodox priest, he apologized. For something he had nothing do with. But that’s what a good father does. He picks up the slack for the derelicts and the dead-beats. When I was growing-up in the 1970s, one of my favorite TV shows was “Little House on the Prairie.” While the titular Ingalls family was largely made-up of females, stories in the series often centered around the boys and their fathers in the nearby town. Much of the time, when there was a neglectful or abusive father, the other men in the community would come together to help or reprimand the father and support the son. Because Orthodox priests oftentimes have their own families and children, they can offer the fraternal support that many never had. They can’t replace your biological father, but they are physicians of the soul. Not long after I stopped engaging in gay sex, I was so incredibly ill that I had to see a specialist. The procedure he performed on me made my condition worse. After much suffering, I found someone who could help. And anyone who has been butchered and betrayed by an inept or unskilled doctor knows the joy they experience once they find a surgeon who can repair the damage that’s been done. That is precisely what I found in Orthodoxy. Repairmen.

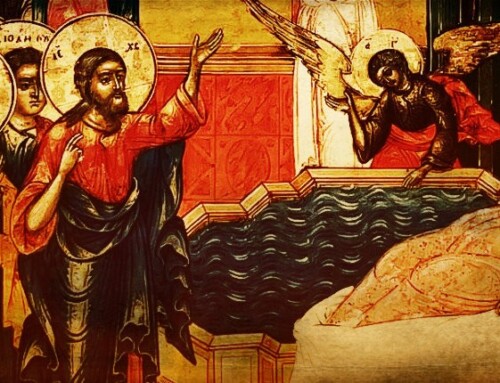

There were still other obstacles; chief among them was learning to trust someone again; especially a representative of a religion; like a priest. But forgiveness was the greatest impediment to gaining peace in my soul; and without that inner silence, I could never fully heal. My favorite part of the Orthodox Liturgy is “The Proskomedia.” It takes place before The Divine Liturgy; before most of the other parishioners arrive; its early; and its usually still a little dark – especially during wintertime. The candles haven’t been lit – and there is a pervasive stillness that almost immediately quiets my soul. During the service, the priest and the deacon say: “O God, cleanse me a sinner and have mercy on me.” This prayer reappears in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. The same Liturgy is also rich with the Psalms, including Psalm 50. “…I shall be made clean.” The importance of ritualistic and actual cleanliness runs throughout ancient Israelite tradition. Its repeatedly mentioned in the New Testmant. In my opinion, most beautifully when Christ heals a leper who approaches Jesus and says: “Lord, if You are willing, You can make me clean.” Jesus then touched the leper, which was forboden among the Jews, and He said: “I am willing; be cleansed.” For this reason, I was rather elated once I learned that I would be received into Orthodoxy through Baptism. For myself, it was a representational washing away of all that happened before.

“It is impossible for a person to begin cleansing himself in everything without having gone through this crucible.” St. Theophan the Recluse

Forgiving the individuals who harmed me in the Catholic Church has been a painful process. It seemed like, the longer I remained in the Church – the more wounds I collected. By the time I left, I was covered in sores. It became a sort of self-flagellation. A sick practice that pervaded Medieval and Baroque Catholicism; see the sad case of Saint Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi who literally beat herself to death. Thankfully, by the Grace of God, I was able to extricate myself from that weird headspace. But along the way, I discovered that those who hurt others, were often hurt themselves. In the Catholic Church this is a sick never-ending process of institutional abuse: boys are abused by priests; a number of them enter the seminaries to become priests – where they are abused; after they are ordained – they abuse young boys. And the whole thing starts over again. But I am not implying that all child abuse victims will become victimizers. Most do not. But abusers are sometimes clustered inside of an institution that protects and promotes them; for example, the Roman Catholic Church. Realizing that your tormentor was probably tormented, doesn’t take-away what they did to you, but their evil carries its own punishment. The Prophet Jeremiah wrote: “Your own rebellion will chastise you, and your vices will convict you. You will know and experience the bitterness of your forsaking Me.” I’ve been there. And it’s the closest thing to hell without the benefit of being dead. Do I feel sorry for those who abused me? No. Not really, But I pray for their conversion. My feelings towards the Catholic laity are bit more complex and still exist as a source of sorrow. A survivor once said to me: “I think the laity blame us for the crisis.” I believe that’s mostly true. Hence, the repeated propensity for the Catholic laity to side with the hierarchy; to believe the bishops when they claim that the problem is in the past; and most importantly – to continue to financially support the Church. I pray they will one day accept the truth.

So, in Orthodoxy, over the past couple of years, I honestly have confidence that I’ve progressed further towards healing than I did in two decades of Roman Catholicism. The reason for this is a little difficult to explain. Partly, it has to do with simply removing myself (physically) from an institutionally abusive organization where I was continually confronted by abusers, enablers, and deniers. In Orthodoxy, at least I have found men who are kindhearted. As I discussed at great length with Gene Gomulka, the Roman Catholic seminaries are essentially brainwashing centers that test an applicates’ loyalty to the hierarchy of the Church. No matter what. This results in denuded semi-pathological priests. So far, I haven’t seen that in Orthodoxy. With a wife and family serving as a safeguard against the destruction of a man’s will. Now, that I’m around healthy people (or at least men who are trying to be) I don’t want to be among the walking wounded anymore. In the Catholic Church, I had to cover-up my own abuse. How could I heal while doing that? I couldn’t. Today, I have hope. I never had that before. I thought: This is as good as it gets. Because, as many in the Catholic laity always said to me: “Where will you go?” As the “prodigal son” did before me, I’ll pull myself out of this hole and wash the filth off my body. And start over.

The greatest statement I ever read concerning the forgiveness of those who abused me – is this. Saint John of Kronstadt wrote: “Every person that does any evil, that gratifies any passion, is sufficiently punished by the evil he has committed, by the passions he serves, but chiefly by the fact that he withdraws himself from God, and God withdraws Himself from him: it would therefore be insane and most inhuman to nourish anger against such a man; it would be the same as to drown a sinking man, or push into the fire a person who is already being devoured by the flame. To such a man, as to one in danger of perishing, we must show double love, and pray fervently to God for him; not judging him, not rejoicing at his misfortune. For my sake, says Jesus, but for their sakes, too. ‘Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them who despitefully use you and persecute you.’” (Mt.5:44)

Thank you, Joseph. Nice, articulate description of the transition from a hedonistic, worldly way of life to one of repentance and purification. A transition faced by everyone living in the Orthodox Church, no matter what their psycho-social history has been. Well-expressed against the background of flawed Roman Catholic theology and its practice, moving towards the correctly ascetic, lived and embodied dogma of the Orthodox Church.