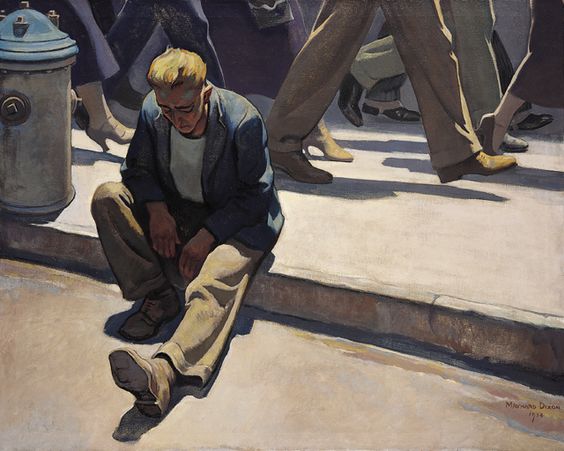

I never thought I’d be one of those people. I grew up in the North Bay – that largely agricultural, suburban, and affluent section of the San Francisco metro-area that comprises Marin, Sonoma, and Napa counties. When I moved to Berkeley to attend CAL, I was shocked by a lot of what I saw – homelessness, used hypodermic needles in the gutters, and the sometimes erratic and even violent behavior from those who wandered from People’s Park to the Marina. Walking to campus from my apartment every day, I had a set route. Eventually, I got used to stepping around people who were sitting or lying on the sidewalks; I expertly maneuvered around the human obstacles in my path; and occasionally encountered the same set of pan-handlers asking for money. At first, I would give them a few dollars. In the morning I would routinely eat my breakfast as I walked. Instead of change, a couple of times I offered a homeless person a banana or a bottle of water; usually, they didn’t want it. I talked to a few of them – they had tragically sad stories: abuse at home, alcoholism, and mental illness. I felt sorry for them, but I thought they were particularly (if not largely) to blame for their current own circumstances.

During my junior year, I started to show up late for all of my courses. For the lectures held within the big auditorium classrooms, this was never a problem as the professor hardly ever looked up from their notes. In the much smaller seminars, my regularly tardy entrances usually caused a notable distraction for everyone present. Following one such occurrence, the professor, who had been until then incredibly patient, took me aside and asked about why I was always late. I didn’t have an answer; at least not one I wanted to reveal to him. For the past few months, I started hearing voices in my head. I didn’t feel as if I were going crazy; I thought I could simply hear myself thinking. But I frequently had arguments with myself – I instantly thought of those who loudly talked to themselves, or some imaginary companion, on the street corners of Berkeley and San Francisco.

Sometimes I would leave my apartment, walking towards campus, intending to be on-time for my next class, but then I found myself getting distracted and taking a detour or I eventually ended up somewhere else. After my regular walk to campus, and before I took a seat in the classroom, I usually stopped into the restroom. Certain public lavatories were considered “cruisy” by gay men. Having been a gay porn-addict since I was a kid, I knew the various possibilities and scenarios well. Most of the time, I had sex with strangers after making momentary eye-contact at the row of urinals. Later on, I could spend all of the same day and much of the following night at a nearby bathhouse. Emerging into the darkness of the night, and being blinded by a dim overhead light-pole, I stumbled over to the nearby Aquatic Park and joined an impromptu all-male orgy taking paces in a clump of secluded bushes. On a semi-warm evening, I’d fall asleep on the ground to only awaken covered in moisture after a cold fog moved-in over the Golden Gate Bridge.

Afterwards, I usually didn’t remember where I had been or what happened. I was surprisingly unconcerned, even when I woke up at home – soiled and stinking. One day, I opened my eyes and discovered myself leaned up against my front door. My life was spinning out of control, but I thought I was finally free. In my estimation, I had grown up in a repressive state of denial. Now, I was free to explore and express my true-self.

“Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth had a 120% increased risk of experiencing homelessness compared to youth who identified as heterosexual and cisgender.”

For much of my life, I was always particularly fastidious about my personal appearance – especially cleanliness. But I started to not care anymore. I would go several days without bathing or changing my clothes. I stopped brushing my teeth. I smelled of cigarettes and weed. I missed more classes than those I attended. For some reason, I could comprehend that my college career was coming to a sad end. That sacred me. I thought, I’d have to go back to my former desolate life. I went to see a doctor. He diagnosed me with clinical depression. He prescribed some medicine and sent me on my way. Every day, I took the pills. I didn’t notice any difference, except that I sometimes felt a little sedated. Later, I wondered if others were trying to control me – through these medications. In my estimation, I was an artistic visionary. Pharmaceuticals were only inhibiting my imagination.

In and around Berkeley and San Francisco, I befriended other would-be dreamers and prophets. The people I once tried to ignore as I passed them by on the streets – I now regarded as fellow travelers. But a life of illusory total freedom took its toll on both my mind and my body; my health began to precipitously deteriorate. During the cool and rainy winter months, I would sometimes wander aimlessly for miles. I continually wore the same pair of blue jeans that became increasingly heavy as they got wet. I endlessly shivered during the day. At night, I burned with a slowly climbing fever. For a while I ignored it. One day, as I walked about campus, I heard about a dead body that was discovered nearby – in one of the University’s parking garages used by commuting students. A few hours later, it was announced that the deceased was merely a homeless person who fell asleep in the garage…and never woke up. The previous palpable tension was almost immediately alleviated: It wasn’t foul-play and it wasn’t a student. But someone must have loved that person? Or maybe no one did.

There are many ways to kill yourself. A friend described one method as “passive suicide.” This doesn’t entail slitting your wrists or putting a gun to your head; it doesn’t even involve slowly dying of alcohol or drug addiction; this form of self-inflicted death results from merely giving-up. Somedays, I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning; somedays, I didn’t want to eat; or I would sit in front of the television all-day – watching the same infomercial over and over again. I felt like a ghost – that drifted about its former residence, hopelessly going about their usual tasks, but not realizing they’re dead. It seemed as if I no longer participated in the world, but simply observed it. For the most part, I subsisted solely in my head. At one point, I began to take a more active role in my own demise, in order to touch material existence, my efforts to feel anything became increasingly desperate and hardcore. My sex-life turned sadistic and violent. More than once, I hoped that one of the numerous strangers I chanced upon would just kill me. But none did. Yet when my actions finally drew death ever closer, I got squeamish and panicked; after all that, I didn’t want to die…at least not like this; for I found myself face down in the mud – with pigs. And, like many prodigal sons before me – I turned towards home. However, unlike a number of those that passed away silently in an alleyway or a parking garage, I knew that I had a place to go. Somewhere safe. I tried to heal. The body slowly mended, but my mind remained the same.

Life became progressively more meaningless and the only certainty played out in my mind. At first, it was as if every paranoia were true: They are talking about me; Someone is following me; There are unseen forces trying to destroy me. I sought help. Initially I came across several psychiatrists and counselors who validated my delirium. According to them, I could define my own truth. Only, this so-called truth had turned into a nightmare. When a Catholic priest told me practically the same thing, I knew that something was wrong. Who or what was trying to convince me of something?

I was starting to believe that I was cursed – perhaps from birth. Then, somehow, I met a psychologist who primarily wanted to listen – not persuade me. It didn’t happen overnight, but I began to feel comfortable discussing certain topics – like my past. Finding the ideal psychiatrist isn’t easy – and sometimes maybe they only exist in the realm of fiction; like the kindhearted Dr. Berger (played by Judd Hirsch) in the movie “Ordinary People.” But a good therapist should be both compassionate and challenging. Because in our sessions, I started to wonder: Maybe I wasn’t made this way. I wasn’t born ill, sick, or disordered. Although there are arguably biological and genetic determinants for mental illness, childhood trauma can also have a profound influence upon mental health. Looking back, it seemed as if I continually attempted to reenact the former abuse. I was caught in a self-destructive feedback-loop that I couldn’t escape. I felt trapped. This results in a physical response to intense and sustained anxiety. I couldn’t sleep. My stomach hurt. My muscles were perpetually tense. I was exhausted. I was always instinctively prepared for another assault. In a way, this had helped me survive for many years. But such hyper-vigilance was taking its toll. I had endured through every repetitive abusive situation I placed myself, trying to make the pain of the past go away, but I wasn’t going to survive myself.

In this respect, medications were vital to my eventual recovery; for they alleviated the physiological symptoms of extreme stress. Only when my body began to heal was I able to turn my attention to the mind. And this proved much more difficult. Because I could perceive most of my physical wounds with the senses: I could see them and touch them. The damage done to my mind were hidden. Admitting that they were there – was the first battle. So far, they had run my life. Eventually, they were going to kill me.

As a society, we have failed hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people who have been thrown out onto the city streets. Many of them have family and friends who love them. But few, even caring relatives, are equipped to counsel (let alone treat) someone with even moderate mental illness. And these same families often find it difficult to locate resources or support – especially for those who are financially insecure. For the most part, psychiatric counseling is not covered by insurance and in many areas, there is a shortage of mental health professionals. In past generations, those with mental illness were often placed into asylums or sanitariums. Nowadays, there is a stigma attached to such institutions – particularly after the release of the 1948 film “The Snake Pit.” In the past, those who were mentally ill were certainly abused in those places, but what is the alterative – doing nothing? Leaving them on the streets to die? Pretending the problem doesn’t exist? Ironically, the situation is the gravest in states and cities with a reputation for progressive policies. Among those who claim to care – the suffering is the most visible and uncontrolled. Why? In my opinion, leftists have been unable to address or even acknowledge the social ramifications of their own ideology: the urban landscape of gang warfare; the rise of clinical depression; and the cross-cultural blight of drug addiction. And how this human misery is related to the breakdown of the family, the sexual revolution, and the multiplication and ever narrower identity groups. Isolation and fear, acerbated by the dissolution of family and community support, has given rise to a plethora of feeble substitutes – including the proliferation of pornography, the obsession with social media, and the escapism of alternate realities. But these replacements prove ultimately shallow and give rise to anger and resentment on a widespread cultural level. Those who have been truly brutalized, including the mentally ill, are abandoned and forced to fend for themselves.

This is tremendous!

Thank you. You spoke the truth of it: “…childhood trauma can also have a profound influence upon mental health… it seemed as if I continually attempted to reenact the former abuse… in a self-destructive feedback-loop…”