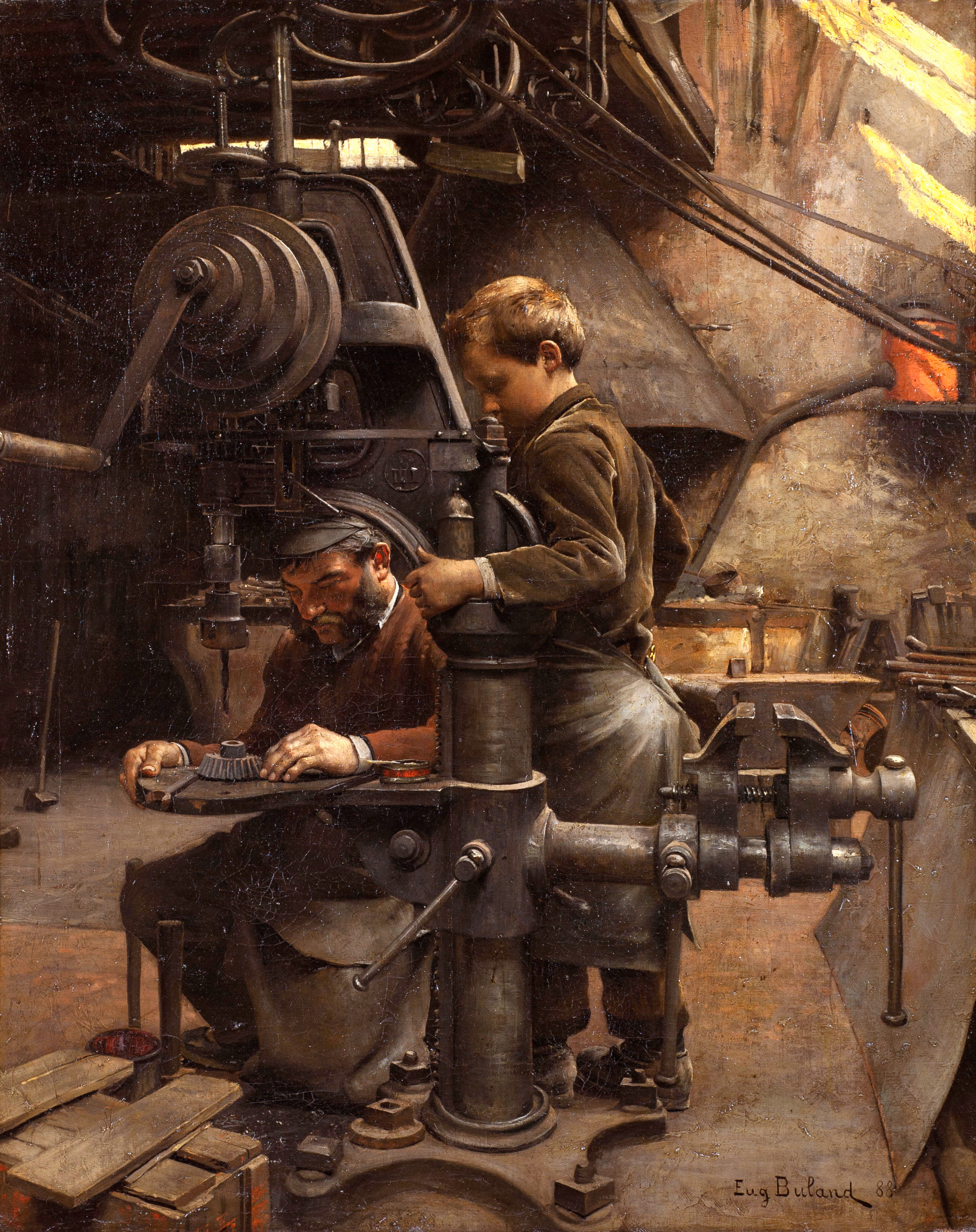

Above: “Un Patron,” or “The Lesson of the Apprentice,” (1888) by Jean-Eugène Buland.

“Mastering a trade gives you a sense of competency, confidence, and completion. Something positive happens when you get good at doing work that has a beginning and an end.” – Mike Rowe

According to Mike Rowe, the host of the successful reality show “Dirty Jobs,” the original idea behind the series was for Rowe to take on the role of “apprentice” when he would profile the various men and women who work at blue-collar jobs across the US. Hence the title for the series, most of the jobs featured on the show involved large amounts of grime, grease, and multiple moments of the audience being potentially grossed-out. For the most part, these often dangerous and thankless jobs are performed by men; not always, but a number of these men are not highly educated in the traditional/formal sense of college or university degrees. Mike Rowe himself has repeatedly recalled how his grandfather only received a seventh-grade education, but he remembered that his grandfather “was smarter by far than most educated people I know, and mechanically gifted in ways I continue to envy.” This reminds me of my own father, who never received anything beyond the equivalent of a grammar school education. When I was a boy, I marveled at how my father was able to fix an intricate piece of machinery, lift a heavy sack of cement mix, or drive a massive tractor with apparent ease. When I would try to help, I inevitably got in the way. I wasn’t mechanically inclined; at best – I was a nervous and unsure clutz. Mike Rowe remembered:

“I wanted very much to follow in my grandfather’s footsteps. I wanted to be able to build a house without a blueprint. I fully expected, and assumed, that I had inherited the ‘handy’ gene, which everyone in my family seems to have. But, it’s recessive — I didn’t get it.”

He added, although he is not “incompetent” at certain trades, he simply has to work harder than other people at getting something done; he stuck with it; he didn’t give up. This sense of determination is what made “Dirty Jobs” so compellingly watchable. For example, I couldn’t imagine even attempting some of the tasks, albeit only for the day, that Mike Rowe tackled on the show: climbing down into a city sewer, cleaning a slimy alligator sanctuary, or following an exterminator into the basement of bug infested building. And, in the midst of the grubby overalls and dirt under the fingernails, Rowe was able to imbue these men and women with an almost visible aura of nobility.

Since “Dirty Jobs” left the air (except for reruns) in 2012, the best show currently on television is The History Channel’s “Forged in Fire.” Like “Dirty Jobs,” “Forged in Fire” is primarily a male-dominated show – actually even more so. The format of each episode consists of a competition between four blacksmiths who must design and a create metal weapon inside the specially outfitted studio. The judging panel (all-male) consists of weapons experts, designers, and specialists in metallurgy – with martial arts instructor Doug Marcaida, in my opinion, as the most dynamic of the group; it is Marcaida who tests each weapon (in mock combat). What separates these judges from other such talent-competition shows (such as “American Idol”) is the lack of Simon Cowell-style mockery. Even when the blade of a competitor completely fails, the judges do not belittle anyone; they are highly demanding, but not demeaning. This sense of camaraderie, is reflected in the interaction between the competitors themselves; unlike the gay-male dominated “Project Runway,” there is an almost complete lack of back-stabbing, bitchiness, and jealousy. There is also a noticeable absence of age-ism, with maturity and experience sometimes outweighing the physical strength of youth. In fact, those who are more adapt or skillful are admired by the other competitors.

I believe one reason for this marked difference is the continued practice of “apprenticeship” in certain (primarily) blue-collar professions. In order to become proficient in a specific trade, there is a need for hands-on experience; not an education which exclusively consists of lecture-style instruction in a large auditorium classroom. In American secondary-education, apprenticeship has survived only in so-called “shop” classes. Before the industrial revolution, apprenticeship was the typical way young men were trained in skilled labor and eventually entered the workforce. With the 20th century rise of the service industry, young men have become increasingly dissociated from manual labor – as well as from the once exclusive world of men. This massive societal shift essentially removed the father from the home: due to long work days, grueling commutes, or the breakdown of the family unit. This void has created the multiplication of feeble replacements; these include: urban gangs, homosexuality, and the peculiar rise of hyperactivity in boys. During the initial years of the gay-liberation movement, the popularity of The Village People, a disco group comprised of almost every conceivable male trope, revealed the intense longing within gay men for some sort of connection to traditional forms of masculinity that they were excluded from as boys. Some young men, when they are growing-up, have other outlets, such as team sports, martial arts, or scouting, that will afford them the opportunity to interact with other boys and to be influenced by healthy adult male role-models – Mike Rowe became an Eagle Scout in 1979.

For someone such as myself, a man with a history of same-sex attraction, “Dirty Jobs,” and especially “Forged in Fire,” is incredibly instructive; because I never experienced any significant form of reassuring male heterosexual interaction when I was a boy or a teenager; it has been difficult to overcome an almost instinctual fear of men and traditionally masculine environs. For this reason, in the gay male community, there is a curious reproduction of such environments – from a sex-club that looks like an auto-mechanic’s garage to an old-fashioned barbershop run by burley men. In reality, the sex-act itself becomes a weak replacement for the fatherly hug.

The cross cultural universality of masculinity is also clearly evidenced in “Forged in Fire” with the forge assignments often entailing the making of a sword, knife, or some other weapon from a variety of diverse cultures and time periods; this creates the incredible situation where a man from Utah can make a weapon (the Kpinga) that originated with the Azande of northern Central Africa. Such weapons are often used across all cultures as an indelible part of male-initiation rites that signal a boy’s passage into adulthood. A perverse simulacrum of such customary practices has survived and been perverted in the West as evidenced by the inner-city landscape plagued by gangs and gun-violence. Among those boys who would not typically coalesce (either due to temperament or outward affectation) into a gang environment, there can be a move towards a false sense of male solidarity to be found in the gay male community.

Two examples of fathers from reality television who seem to be getting it right are Jan Pol from “The Incredible Dr. Pol” and Ben Schroeder from “Heartland Docs;” both airing on The National Geographic Channel. The two men are practicing veterinarians working in primarily rural areas oftentimes with livestock. On his show, Dr. Pol’s almost constant companion is his adopted adult son Charles. Their relationship is frequently convivial and informal, good-natured banter and kidding are a part of their conversations, but Charles always shows a certain deference to his father – especially when they are out in the field. Their ability to laugh at the other’s teasing is a sign of a close bond; on the other hand, in a father-son relationship where there has been a history of overt criticism and neglect, any sort of ridicule (with malicious intent or not) is immediately viewed as an attack; this is particularly devastating in young man who will later “come-out” as gay, since male homosexuality and low-self-esteem are closely associated. For this reason, fathers have a difficult balancing act to perform – one that includes a certain amount of masculine rough-housing yet never collapsing into irreverence.

Another good example is Ben Schroeder with his two teenage boys. Schroeder’s father was also a veterinarian, and he often recollects accompanying his dad as he made his rounds at the various farms – tending to sick or injured large animals. Consequently, Schroeder often brings one or both of his sons along with him – while his wife (who is also a vet.) remains at the couple’s clinic – taking care of their smaller patients. This all-male time for father and son is important. Generally, fathers have a different sense of imminent danger and the risks sometimes entailed in physical labor; wherein a mother might intercede prematurely to maternally protect her child. With their father, it is important that boys and young men (especially those of a more sensitive or awkward nature) are able to explore their boundaries. Without that chance, boys will oftentimes be relegated to the company of their mother and other women and girls – like myself, imaging a world where I could join the company of men; later that dream was only realized among gay men. One significant case study found that:

A mother cannot provide for the boy the male model he needs and is searching for, the male who would affirm him in his maleness.

A lack of male role models in a boys life can also set him up for possible abuse by predatory men; in my case, I so intensely longed for any sort of masculine approbation that I became a frequent target for victimization. In fact, 46% of the homosexual men in contrast to 7% of the heterosexual men reported homosexual molestation.

What all of these shows have in common is a mutual admiration for the working man. I live in an area of California that is often-congested with upper-class tourists. One day, as I was driving along a country lane – I came across a group of workers (all-male) who were repairing one of California’s many delipidated and neglected roadways. I stopped a few cars back from a man holding a sign directly under the hot sun. He stood relatively still, but he sweated profusely. I could see the men toiling away, dirty and soaked in perspiration, over the steaming and stinking asphalt. From nowhere, a couple of overly thin middle-aged sun-tanned guys showed up on their expensive bikes – wearing skin tight florescent-colored racing outfits and looking remarkably dry and neat; they seemed odd when contrasted with the appearance of the nearby road-workers. Which is a true image of masculinity? In my mind, one represents a genuine type of male self-sacrifice, the other a corporate detachment that is indicative of the Machiavellian self-interest that is often in evidence on “Project Runway.” It’s the difference between James Evans on “Good Times” and Don Draper on “Mad Men.”

I grew-up rather horrified and embarrassed by my father’s blue-collar status; looking with disdain at his roughly calloused hands and muddy work-clothes. Today, I see many things differently. Primarily through a growing devotion to St. Joseph – the spouse of Our Blessed Lady and the foster-father of Jesus Christ, I can now admire the labors of those who work with their hands. Because such work does not simply require brut force, but as I witnessed what my father created in the landscape – for example, to till the soil also takes a great amount of thought and ingenuity. But society has greatly lost that realization that was once embodied in the so-called “gentleman farmer” with the last memorable appearance of such a man in Kevin Costner’s role from “Field of Dreams.” However, a man does not need to be indelibly linked to the land in order to maintain a sense of attachment to more physical acts of exertion. For example, those who work in an office or retail space – as a lawyer, engineer, or clerk, can still tangibly connect with himself and his children through at-home projects and by fostering a family-wide interest in the outdoors: camping, hiking, and fishing or hunting. Some men believe they accomplish this in a rather narcissistic way by joining a gym. Except, as I have noticed on the California beaches – the sometimes maligned but fit “dad-bod,” when compared with the pumped physique of the bodybuilder, looks more genuinely masculine while the latter appears to be strangely artificial.

Unfortunately, this is what we have been left with in society – an illusion of masculinity. But true masculine heroes can be found in the most unexpected places: in a carpenter shop in a Galilean backwater; underneath the hood of a car; or on “Forged in Fire.” Before they disappear – young men must be invited into these spaces in order to ensure their continued existence and the survival of authentic manhood.