“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.” ― Chuck Palahniuk, “Fight Club”

Almost three years after the 2017 California firestorm, that cost me my house, all of my belongings, and ultimately my father, a strange mid-summer flareup of dry-lighting caused numerous conflagrations around the State – including several burning precipitously close to my new house; maybe I was foolhardy, but I returned to almost the same footprint left by the ruins of my old home. I’d been there less than 12 months.

For the majority of my life, I ran away – from everything. I was a scared boy. Constantly dreaming. Imagining a land that was somewhere “over the rainbow.” Where all my weaknesses would be restored – someone would bestow upon me everything that I lacked; particularly: courage. For, my fearfulness started at a young age. I was an unusually sensitive kid; the often unintentionally cruel teasing by boys at school left me unconsolably wounded. So to speak, I didn’t shake things off.

I remember a markedly humiliating incident involving an especially mean boy from school, one of my older sisters, and a day at the local pool. Minding my own business, a boy decided to viciously bully me; my sister came to my rescue; and I cowered away; hoping he would simply leave me alone.

Back at school, an older boy assaulted me in the restroom.

Inside the classroom, I said little and tried to blend into the background. At recess or lunch, I endlessly daydreamed and methodically planned my eventual escape to San Francisco – a place where I could finally “hang out with all the boys…”

In the meantime, I exhibited a strange combination of extreme timidity and shyness and an impulsive need to belong and to be accepted. I was hesitant, but incredibly naive and trusting. One night, in a parked car, a man touched me.

It seems counterintuitive, but early experiences of trauma – instead of driving us away from similar situations, the memory (or the subconscious need to heal it) repeatedly compels us towards an inexplicable form of reenactment.

As soon as I could, I ran away to the gay capital of the world – the Castro District. Unlike my desolate life before, which wavered between loneliness and almost complete isolation, I was constantly on the move. In quick succession, I went from one relationship to another; then from one party to another; from gay bar to bathhouse; I never stopped – until I crashed. Then, I couldn’t run away anymore. I had to crawl.

After a short time of recuperation and physical healing at my parents’ house, I felt an overwhelming need to run away again. I sensed that I wasn’t safe. For some strange reason, I returned to the Catholic Church. Almost immediately, I was traumatized and triggered by the same type of priest who molested me; the same priest who rather easily convinced a naive teenager that God made him gay. They frightened me.

Still highly guarded, I tripped into the isolated world of “traditional” Catholicism. For good reason, abruptly, there were few parishes or Masses that I would attend; Sundays involved a long round-trip drive to San Jose or Sacramento.

Knowing nothing about Catholic religious orders or priestly vocations, I left California for the East Coast – in search of a secluded refuge from the chaos of the world. But I couldn’t escape. Very quickly, I thought I was going mad because where I found myself, in many respects, was gayer than the place I just escaped. I believed that the demons which often haunted me in San Francisco had followed me there; I thought that they were responsible. Therefore, I ran away again.

I found another temporary home; and then another; and another. Whenever I started to get comfortable, I was quickly cast back out into the maelstrom. Except, there came a time – when there were no more places to hide.

A certain monk, afflicted by many sorrows, said to himself, “Leave this place.” With these words he began to put his sandals on his feet, and suddenly he saw the devil in the form of a man sitting in the corner of his cell. The devil was also putting on his sandals. He said to the monk, “Are you leaving here because of me? Well then, wherever you go, I will be there before you. – St. Ignatius Brianchaninov

In a sense, I came full circle – I returned home. Although, for probably the first time in my life, I truly appreciated what my parents had done for me; my relationship with my dad remained awkward and occasionally strained. As a result, I didn’t particularly want to be there. Avoiding my father was far easier than addressing our differences; before that, finding a new pseudo-daddy was better than dealing with the one I had.

With the help of some faithful friends, a good spiritual director, and an excellent mental health professional – I gained the strength to not only confront my fears, but to defeat them.

The devil is a bully. He calls us names, in my case: sissy, faggot, homo… Sometimes those epitaphs hurt as if we were attacked by a thousand blows. You skulk away – beaten and disfigured. However, evil is insidious. Slowly, what was once incredibly demeaning becomes oddly acceptable – even self-imposed. I had done that long enough in the secular gay male community; now, I wasn’t going to allow evil men in the Catholic Church to define me.

Sometimes you have no other choice but to leave: if your life is in danger; if you are being abused; if your health is compromised. If there is no one to save inside, you don’t run into a burning building. Self-sacrifice and suicide are not the same thing.

There is also a spirit among us that might cause someone to confuse wholly decent and well-founded concern with hyper-criticism and rejection; this misunderstanding becomes more profound when combined with earlier memories involving what is perceived as parental disinterest or negligence. When I had lost everything; when I literally had nowhere else to go – I had to face what I always wanted to desperately avoid: the past.

After all those years of torturous wandering into oblivion, my dad wasn’t as bad as I thought; for a few years, I stayed home – and I actually started to like him; but then, he was gone. The 2017 fires took everything away from me; most of all – my father. But I’m thankful that I had that time – as short as it was.

2020 – a bad year after a series of bad years: the loss of my father; the sudden death of a good friend; ceaseless health problems; corruption in the Catholic Church.

In 2018 and 2019, after my father’s death – I retreated to a little room in an empty house; my sole possessions: a mattress and box-spring, some donated clothes from a friend, and a holy-card of St. Joseph. I survived. I thought that was enough. But, as I had done before, my universe became increasingly small. At first, I wouldn’t travel beyond the San Francisco Bay Area, then I restricted excursions to town, then I didn’t leave the house; soon, I couldn’t step outside my room. My attempt at insulating myself from the world didn’t result in feeling protected, but in feeling less secure. I was losing my mind.

Like before, I forced myself to confront my fears. A good friend (once again) was there to help me; in a sense, he made a more conscious effort to step forward on my behalf – knowing that I always longed for a father-figure in my life; and the only one I ever knew – was gone. But, then, he too was gone.

All too soon, less than 3 years after the devastating inferno that took so much away from me – following a few incredibly hot and dry weeks – they returned. Suffering from chronic asthma since childhood, soon after the fires began, the air inside and outside of my house became increasingly difficult to breath. In search of a respite, I headed towards the clearer skies of San Francisco.

Right away, I felt better. Away from the heat, smoke, and lingering memories of death and destruction – I thought, I might stay for a while. Then, I got a phone-call. The flames, that were rather distant from my house, had gotten closer. Evacuations were imminent.

I rushed home – hoping to save a semi-feral cat I had been feeding and to remove a car I left behind. As I drove north – I sarcastically sung to myself “Mamma mia, here I go again…” Resembling a volcanic eruption, in front of me arose a giant plume of rising smoke. For a few minutes, I went into full-diva mode; decrying my bad luck, torturous existence, and ceaseless misery. Woe is me. My instinct was to turn the car around. Only, I didn’t.

When I got to my house, I couldn’t see any flames, the winds were light, but the smoke was heavy and thick. I felt trapped. I acted like a spoiled debutante; throwing things into a suitcase as if I were Scarlett O’Hara trying to flee the eminent burning of Atlanta – to save myself from any more suffering, I could have imagined trampling over anyone. In some cases, including mine, victimization can transform into a sense of entitlement.

I don’t know exactly how or when, but I made the decision – I am not going to do this again. Almost three years before, with my aged father in a wheelchair, my only concern was getting him to safety. Now, I no longer had that looming obligation. I had lost everything – maybe, for the first time in my life I was truly free.

In a matter of minutes, I decided to stay. While I would never recommend that anyone ignore directives from firefighters or first responders, I reached a personal resolution, based upon the observations I made of the situation: that I had an arguably good chance of surviving. For example, in therapy, I explored the ability to discern risk and exposure to triggering situations; to flee whenever one smells smoke – is an overreaction by someone who survived a fire; for the most part, that is the head-space I have been in; conversely, recklessly skiing through a high-country region marked “Avalanche Area,” is just foolhardy and irresponsible.

“Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” – T. S. Eliot

Unlike the conditions surrounding the 2017 firestorm, in my vicinity – the winds were calm to non-existent, the previous thirty or forty years of growth had largely been burnt, and the possibility of another downed tree blocking the only escape route, as was the case before, seemed an improbability.

For three days I didn’t sleep very much. I stayed awake and watched the movement of a distant red glow on the eastern horizon. Slowly, it began to lessen in brightness, and then it disappeared altogether.

But I wasn’t alone. In the surrounding ranches and wineries were stalwart men who oversaw the care and upkeep of large vineyard properties; some of them had also been through this before. Almost immediately after the fires in 2017, I remember one man telling me how he urged his son to quickly leave during the early-hours of the chaos, while he stayed behind and was eventually trapped by the flames; while he survived, all of the homes provided for the vineyard workers (including himself) were destroyed. On an ordinary day, these men are formidable; but as often comes from growing up in hardship, as my father assuredly experienced as a child in war-torn Italy, a life of early suffering can make you a strong man; or in my case, they can make you perpetually afraid.

In hardship and tragedy, a strange camaraderie is formed; the last time I experienced such kinship with other men was during the AIDS epidemic; but in those dark days, there was suffering without redemption or resolution.

Throughout his life, although I thought he was just simply proud and obstinate, my father was often courageous and steadfast. He had to be. Like his patron – St. Joseph, he carried the frequently heavy burden of being a husband and fatherhood. My dad was poor and uneducated, but ambitious. I grew-up with many of the advantages that he didn’t have when he was boy; but I was wounded by a different type of war during childhood; in the US, the sexual revolution resulted in another type of causality list: with millions of deaths through abortion, the devastation upon the human mind due to sexual abuse, and the countless souls who were touched by the ravages of AIDS. For the most part, I couldn’t move on; while my father, despite his childhood in Italy, those early struggles seemed to compel him forward.

There’s an oft-repeated saying – from Friedrich Nietzsche to Kelly Clarkson, that goes like this: “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.” That’s not always true. Sometimes, you barely survive; and there is a sense of triumph in that. Especially after repeated abuse and devastation – it gets progressively more difficult to come back – if it at all. And there is no shame in that. Sometimes, its all we can do is live through another day.

“I am a series of small victories and large defeats.” ― Charles Bukowski

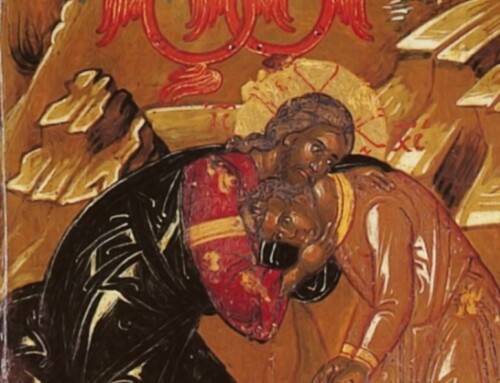

I’ll never be like my dad; I can’t do the things he did. In 1981, when a devastating fire swept through almost the same area as the fires of 2017, my father risked his life to warn firefighters about an aged and disabled woman whose husband was not at home. When they got there, she had already been evacuated, but they saved the woman’s home from the flames; in 2017, that same house didn’t survive. But the greatest rescue my father ever accomplished didn’t require him to brave the smoke and flames – he saved me from a chair in his house; where he prayed endlessly before an image of St. Joseph and the Christ-Child; he prayed for me, sacrificed his anguish, and eventually I would return home – scorched, but alive.

I have faced many hardships, tragedies, and traumas in my life. Oftentimes, they have hurt me severely. The pain has been unimaginable. But I don’t know if I am any stronger than I was before – in terms of my physical endurance, I am at a greater disadvantage than when I was in my 20s and 30s. However, as I grow older and the majority of my life is behind me – I have become somewhat bolder and more uncompromising; I worry less (or not at all) about what others may think. My only concern is the will of God.

I am tired – I am tired of running away. Increasingly, it’s easier to stand your ground. When I was a child, I could be easily tormented by the other boys; probably, that’s why they picked on me so relentlessly. Since then, I’ve been bullied and intimidated; much of the time, I often cooperated in my own oppression. Never again. I am not a little boy anymore. I don’t believe the lies any longer: you are a fa*got; no one will believe you; God made you gay…

I will not die for a lie. At one time, I would. I chose to go to San Francisco at the very height of the AIDS crisis; preferring to die as a young man rather than die a lonely old recluse. For those of use who have bowed down before the lie – the life of Christ is truly one of great heroism and divinity. To die for the truth, for one’s own sake, is truly heroic – my father died everyday when he offered up his pain in reparation for my obstinance – that is an example of extreme bravery; to die for the world – that is God.

No one can push me out of the way – not a lie, not a fire, and not the evil men in the Church. I am staying. And I will fight.

Amen!

Praying for you and for all in California!

You’re very brave to confront all of this, on a daily basis It’s hard to imagine. I am glad you could break through. I have a lot of relatives that are stuck in their modes of protection.

I get stuck myself, although, a bit differently than they do. It’s just a default. When I read stories like yours, it makes things seem more hopeful.

Perspective. How are you different than that “formidable” man neighbor or your father? You don’t think they were scared out of their wits at times while still there or praying from that chair? Fight or flight is tge same reaction to fear; trembling but different results…remaining or leaving. Some cornered animals among us see an escape and some don’t. Age brings some experience…you have experience now like the formidable neighbor and your father and you will gain more…so you stsy and fight though just as scared! That’s the hero! Some die and get the medal postumously…in Heaven. Stand and fight, stay and fight! The Catholic Church is yours, is made up of sinners like you and me and the bishops and priests and popes, perfect only in Jesus’ word and magisterium. If you had a teen son, he would be scated or ignorant and be amazed at what you are doing with standing up against bad priests denying sinfulness and for a Church that needs the light of transparency and disinfectant it needs to become more holy in deed because furture children like you and me and future/current adults like you and me DESPERATELY and fearfully “tremblingly” need it/her and she aint doing as good a job as God Designed her to do and be for us. You’re among the formidable neighbors and dad’s impressing upon the faithful that standing and staying is what is so needed! And you may fall, no problem we all do so don’t put that weight on yourself! Like Colonel Ripley’s order in Dong Ha, “Hold and die”, sometimes we run but after you’ve seen enough and especially after you’ve come to love God as he did, and St Maximillian Kolby did….you stand and stay. And you did and do by bringing to transparency your struggle away and back into the Church. Keep standing, hero neighbor! You have some cajones! And thst is what I and our Church need. Jesus called it love of neighbor, like the Centurion for his slave. Firefighters and cops and soldiers often crumple and sob after a heroing event…fight or flight the same fear, but that time they stsyed. Keep staying, we all need you even if you will likely never hear it. Keep up the good work!

Great piece of writing Joseph—thank you for your brutal honesty and unflinching leadership in this battle for souls. You have a fatherly heart.