Much of my life was chaotic. But it wasn’t always so. At home, as a child, before I became exposed to the wider world, I often felt safe and loved. Yet, almost immediately, in school, on the play-yard, at the neighborhood park, I floundered. I was terminally fearful and insecure. In the animal kingdom, I would have been quickly picked-off by an opportunistic predator. My parents protected me. But this became increasingly the duty of my mother and other female members of my family as my dad was preoccupied or too busy with work.

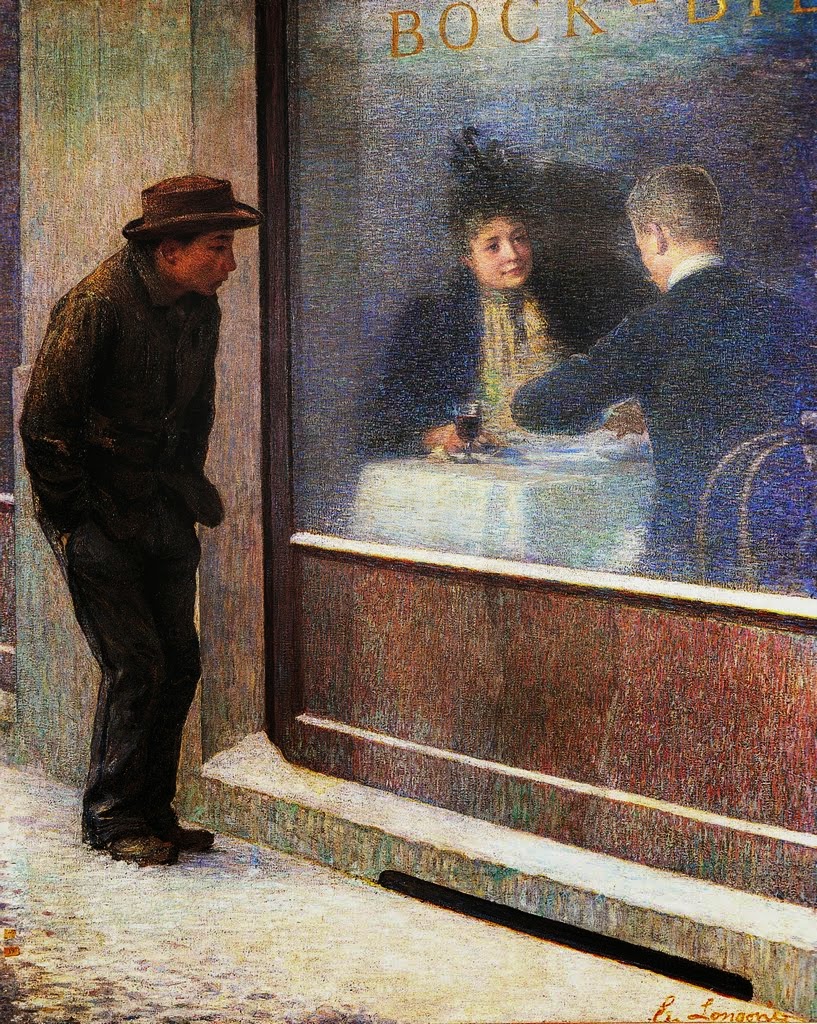

At school, I was the boy who only a few wanted to befriend. I imagined myself as a wayward street urchin cast out into the cold, doomed to always remain an observer of a world that rejected me. As a result, I sometimes clung to anyone who showed me a modicum of warmth and affection. This mentality persisted into my young adulthood when I sought out affirmation and inclusivity in the only place that I perceived as open to me – the gay male community.

In San Francisco, I honestly found friendship, but that comradery often came at a price. Due to my interminable loneliness, and despite the constant threat posed by HIV, it seemed like a reasonable bargain. But, by the end of the 1990s, though the disease was far more manageable and no longer a death sentence, I was looking for a way out; for me, the best possible exit meant death.

In the days leading to my attempted departure from life, I’d spend hours in city parks watching the rare family in San Francisco. I had particularly keen interest in the interaction between fathers and sons. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, this phantasm from my past, from a boyhood that didn’t happen, from a memory of a statue in my dad’s room of a man pressing the Christ-child to his chest, represented my lifelong wound.

For me, the family, but specifically masculinity, embodied stability. When I returned to Our Lord Jesus Christ, I first envisioned this idea after I began to attend the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) at a local church. In my old boyhood parish, there was a noticeable lack of men in the pews; the majority of the congregation consisted of the elderly and mothers with their unruly and disinterested children or grandchildren. Often, numerous female eucharistic ministers outnumbered the faithful; with the sanctuary becoming a chaotic assemblage of various communion cups and etched glass patens. At the TLM, I saw involved husbands and fathers. Like the liturgy itself, their identity emphasized structure and sacrifice. I would watch in awe, when I should have been paying more attention to the Mass, when a father of several very young children was able to balance one kid on his knee while turning another child’s head towards the altar (with his one free hand) as he held a missal in the other. But this type of masculinity did not result in a sort of lifeless rigidity. Instead, it creates harmony and a distinct complementarity. I saw it over and over again observing anonymous Sunday picnics – with a dad pushing a stroller loaded with blankets and toys, lifting a boy on his shoulders, and carrying a large cooler, with the mother striding along holding a single water bottle. But the guy looked overjoyed.

Yet, heterosexual couplings are not free from chaos. I believe that the near-collapse of the family during the post-war era in America created the impetus for many to reenvision the whole concept. Its no accident that the baby-boomers, a generation that collectively benefited like no other before them from the material benefits of the industrial revolution, were the first to try to tear it all down; and then rebuild it – in their own image; or in any other – hence, the momentum for same-sex marriage from primarily older gay men and women. But were they just spoiled brats or had something else gone wrong? As imagined in the quintessential 1950s TV sitcoms – the children of plenty became the teenagers of want; perfectly realized by James Dean in “Rebel Without a Cause:” the story of a troubled boy who simply needs his weak father to stand-up for him.

Meanwhile, I wanted to die; but I didn’t. The next day, though I never could have imagined my life would take such a drastic detour, I turned back towards home. Though I still semi-detested my father, I instinctively knew that he at least could provide a much-needed place to rest for a while.

While I recuperated, remaining in my room during daylight hours, I would sometimes creep into the kitchen to eat. Usually, my parents had already retired for the evening, but on a couple of occasions, I caught my dad praying in front of his small homemade altar. Illuminated only by a votive candle, I could barely hear him as he mentioned the names of certain people – I was among them; the others, I recognized as disaffected members of my extended family. Later, I learned, he had practiced this little ritual for several years. And, I thought he never cared.

As the years wore on, my father continued to pray and I noticed that his suffering intensified. My dad always seemed to deal with some physical ailment, but with age – they became worse. For most of my life, I didn’t know. This wasn’t due to the masculine trope about men who do not complain; it’s that some men place the lives of others above themselves.

I first seriously noticed this sacrificial aspect of some men’s lives when a few of the Catholic dads attending the TLM were kind enough to befriend the single interloper. For the most part, they had larger than average families. They drove lesser expensive cars; their kids wore simple clothes; sometimes, the wife home-schooled the children, though she was educated and accomplished in her own right and could conceivably pull-in a good salary. At first, coming from very affluent San Francisco, I thought the whole thing was hopelessly old-fashioned. But the children looked effortlessly happy and their parents were surprisingly content.

Throughout my father’s life, I knew him to be singularly driven and ambitious. He was a businessman, a builder, and a farmer – he created and cultivated; he did things I could never have dreamed of doing. But I remember him best for being a man of prayer. He prayed the Rosary every day – at least 8 times a day; that’s over 400 Hail Marys. Its that sort of heavy lifting that saves souls. Accompaniment, discourse, and dialogue doesn’t do it. A father can be there for his child, and not be there at the same time; they can talk to their son, and say very little. Its not enough for a father to be a good provider. That’s just part of the basics. Like those men who befriended me at the TLM – fatherhood means a kind of holy sacrifice. After years of my father and I struggling with each other, I saw it in him. And it saved me.

When someone you love knocks at your door, embrace them. When a stranger shows-up at your church, even if they look different from everyone else, welcome them. The best examples of Christian life and thought can be found among everyday Christians: in the simple way they go about their daily lives.

For unto this are you called: because Christ also suffered for us, leaving you an example that you should follow his steps. 1 Peter 2:21

Someone is standing out in the cold – whether, as a result of their own choices or through circumstances out of their control. Invite them in. The “prodigal son” was never cast out of his father’s house; he left of his own accord. I did the same. Only one time in my life did my father reprimanded me for my life decisions – because I refused to respect his boundaries. At the time, his were fairly wide; but I purposefully leaped over them. I wanted to push back; to cause a reaction; to hurt him, for hurting me. At that point, there wasn’t much that could have changed my mind. Only when my own misguided preconceptions and prideful stubbornness left me with little else but a destroyed and bleeding body, did I begin to reevaluate everything. Literally wallowing with the pigs brings a moment of instant clarity. Suddenly, that which looked intolerant and judgmental (even old-fashioned and anachronistic) feels like a refuge from chaos. However, especially parents have a difficult time allowing their children to fail – to learn a hard lesson on their own. Agreeing in order to not disagree; avoiding the difficult conversations in order to not have an argument; being complicit is not compassionate. Shunning the truth is like leaving someone out in the cold.

This a thoughtful, and well written article