Ever since I walked into my first San Francisco “gay” piano bar and heard an impromptu chorus of men singing Wayne Newton’s “Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast,” I have been fascinated by songs which resonate with “gay” men; for example, George Michael and Aretha Franklin’s “I Knew You Were Waiting for Me:”

“I know the taste of victory

Though I went through some nights

Consumed by shadows

I was crippled emotionally

Somehow I made it through the heartache

Yes I did. I escaped.”

They seem to all be variations on the theme established by Gloria Gaynor in the gay anthem of all gay anthems – “I Will Survive:” an early existence of loneliness and deprivation, followed by continued abuse and unrealized dreams, and then culminating in an all-encompassing love that blots out the pains of the past. The vehicle through which we travel to this land of uncontested harmony and peace is the dance floor; with the disco becoming a sort of high holy place of transformative grace.

This week marks the 25th anniversary of self-proclaimed “Queen of Disco” Sylvester. I remember walking into one of my first San Francisco gay discos back in 1988, and the DJ playing a homage to the late singer, who had just died of AIDS; a few weeks before he made his last public appearance: being pushed in a wheelchair for a Castro Street parade. But, all images of a grisly and painful death were washed away by the mesmerizing beat of “You Make Me Feel.” It all felt somehow comforting and familiar. As a child of the 1970s, I had been raised on disco. The Village People were a singular influence upon my musical tastes and on how I would later perceive homosexuality and the gay lifestyle. In the 80s, I was peculiarly put-off by the advent of hard-rock and metal hair bands. The one saving grace emerged in the disco-redux genre of dance music, early on, headed by: Laura Branigan, Madonna, and Shannon. By the time I came-out, that had morphed into the Euro-Techno craze of the early 90s. Yet, those old disco songs would always come back. It was almost as if the gay community solely willed the mid-90s disco revival into being.

Within these songs, particularly “Gloria,” “Holiday,” and “Give Me Tonight,” there were these often competing themes of desolation, escape, and salvation by some unseen force. This is most implicit with Shannon when she sings:

Walking sadly through the park

I hear crying in the darkness

And though I act like I cannot hear…

Give me tonight

Baby if you don’t want to stay

Girl, I’ll just go get you

You’ll see I’m right

You won’t get to go away

Love ain’t gonna let you…

This is like a night of “cruising” for a gay man in a public park. As a late-twenty-something slightly beaten up homosexual, I would spend my final days in often chilly San Francisco wandering about the well-known wooded trials and lavatories seeking a quick moment of bodily warmth from another man. This was a desperate plea for human contact that became increasingly inhuman. And, within this hopelessness is a desire for an everlasting release from bondage. In their heavily orchestrated retro-disco song, “Scared of the Dark,” from their reunion album, the 1990s British band Steps, who never gained a large US audience except in the gay dance clubs, have encapsulated the history of the near-suicidal panic and fear of being abandoned that has been the focus of “gay” dance hits:

Give me the bright lights of the dance floor

To shine inside this broken heart of mine

The way you move I’m forgetting all the ghosts in my mind

Just say your mine and stay by my side

Don’t say you’re leaving

Don’t turn out the lights

I scream, I scream, I scream

Don’t let the darkness come and hold me…

The classic disco songs of the 1970s had an almost religious fervor about them, they seemed to mix throbbing percussion with the melody of Gregorian chant and Southern Gospel – the penultimate examples being: Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” Thelma Houston’s “Don’t Leave Me This Way,” and Diana Ross’ “Love Hangover.” Every one of those singles starts at a low and deliberate pace, eventually building to climactic chorus of exuberant ecstasy. When I got to see Donna Summer in concert, at a primarily gay attended show in San Francisco, it was more like attending a revival meeting than a musical performance. I would have a similar experience at a Diana Ross concert. These sorts of drag-queen divas held court over their gay audiences whipping them into a frenzy rivaling the Dionysian ceremonies of Ancient Greece. At the time, it was the closest thing I came to organized religion.

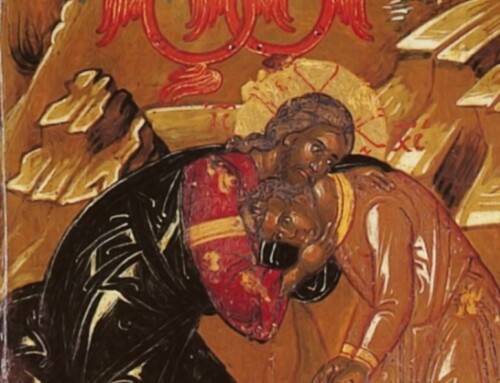

Years later, after leaving the gay lifestyle and saying goodbye to my friends, I found a little out of the way Catholic Church which still clung to the traditional Gregorian hymns and chants. Mixed with the overwhelming sensation of the liturgical rites and the incense, I felt transported once again. Curiously, my mind traveled back to those heady days of dancing until 2:00 am. I thought of my old cohorts, and I was sorry for them. Here I am, kneeling in a Church, and the Love of God is enveloping me in a way I could never have imagined. I was not popping Ecstasy, slipping into a dark hallway for a quick sexual encounter, or sweating gallons as I pushed my way through a crowded dance-floor. I was in heaven. I thought of how many ways, and how many roads I had stupidly taken, deceived by the world, looking for the solace, that was always waiting for me. Disco was the gay grasp out towards the transcendent. Its ideals were noble, but sadly susceptible to corruption decay.

In Jesus' name I pray those trapped in bondage come to Him for freedom. T. W.

“Jesus Never Mentioned Homosexuality”

When gays have birthdays, they don't mention everything they don't want but say positively what they do want.

Likewise, Jesus didn't negatively list every sexual variation He knew mankind would invent, but positively stated that marriage involves only a man and a woman!

Google or Yahoo “God to Same-Sexers: Hurry Up,” “The Background Obama Can't Cover Up,” and “USA – from Puritans to Impure-itans.”