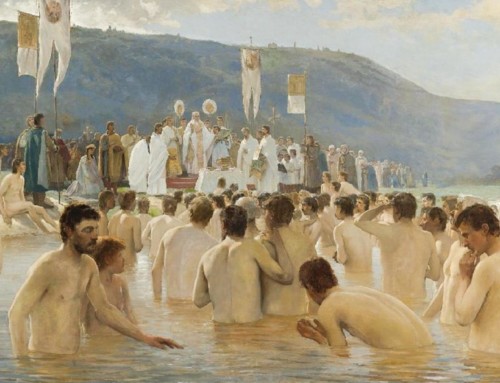

Above: Marie Spartali Stillman, “How the Virgin Came to Brother Conrad in Offia and Laid her Son in his Arms,” 1892.

“What he would have liked, without admitting it, was for the whole world, forever under construction yet never constructed, to be like his own destroyed life.” ― Andrei Platonov, The Foundation Pit

I think I wasted most of my life being angry; and then bitter and resentful. My disappointment started early: I didn’t like myself; I wasn’t like the other boys; I was weak and afraid; I thought I didn’t have the dad I wanted or deserved; the isolation and despair that epitomized my adolescence seemed like some sort of punishment; I imagined that I was especially sensitive and highly imaginative; no one could understand me. For this reason, I was singled-out for torment. As a teenager, when a Catholic priest abused me, many of my previous conceptions of myself were confirmed; I was always destined to be a victim.

What followed, in my mind, were a series of increasingly self-destructive victimizations or re-victimizations. One seemed to lead to the other. And I always played almost the same identical part – that of the lost boy seeking solace from an older man. In hindsight, much of my life became a reenactment of previous abuse; perhaps of the original wound. I couldn’t escape it.

Like some survivors of childhood abuse, as an adult I often found myself surrounded by abusers. Perhaps, I felt I didn’t deserve anything better; maybe I confused cruelty with caring and compassion; or I wanted to make my former abuse seem as if it wasn’t so bad. Because, when I was locked into a cycle of abuse, my constant companions were those similarly drifting through life in silent agony. We never really spoke directly about our pain; we didn’t even acknowledge its traumatic effect upon us. Everyone had similar stories. Ultimately, maybe that is why I was there – I didn’t want to be the only one. In the gay male community, I wasn’t. But our shared and collective misery was most often kept unspoken

The problem with continually reenacting former abuse is that it’s never resolved. I only became increasingly desperate. In a few subsects of urban homosexual culture, the single stopgap to certain downward spirals was death itself; one day, I knew I was going to die. Beforehand, I had already reached a point of ultimate self-annihilation because of my own sense of disillusionment. I wondered if it had all been a lie; sexual liberation hadn’t resulted in freedom, but bondage.

“The whole question here is: am I a monster, or a victim myself?” ― Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

For over a decade, I played my part; although, as I neared thirty years of age, it became increasingly difficult to imagine myself as a lonely boy in need of love. Anyway, that original abuse was long forgotten; during everything that proceeded, I had new trauma to deal with. In reality, that initial moment of betrayal bred a thousand little deceptions. Within the subsequent cacophony of lies, I couldn’t discern the original whisper that said: You were born this way.

For many years, I have been mystified by my own return to the Catholic Church. Why would I go back to a place that harbored such terrible memories? But those boyhood recollections were no longer at the forefront. After subsequent occurrences of abuse and disappointment, the Catholic Church didn’t seem particularly different from the world I just left; some of the pick-up lines were even the same; and it didn’t really matter if they came from an older gay man or a middle-aged priest. At times, they sounded identical. Here, unlike in the gay male community, the replaying of the abuse was almost precise. In a way, it was more traumatic than what happened when I was a teenager.

Only, my faith was the size of a mustard seed. I knew almost nothing. Yet, since I was a little boy, I always associated Jesus Christ with the Catholic Church. I didn’t know where else to go. Nearly fifteen years later, I once again sat alone with a priest; this was the bad remake or the cheap sequel. He didn’t touch me, but I heard the same thing. I trusted again and again. And I was betrayed again and again. Later, I thought back to my friends who died of AIDS – they passed away in what many Catholics would consider a state of grave sin. They too had been betrayed and deceived resulting in the destruction of their bodies. But there is a mutilation of the soul that does not destroy the body; your death is slower and sometimes more painful.

Victimization can cause a lingering anger and hatred that will eventually poison the mind of the survivor; and, as a result, contaminate everyone around them. Examples include: Medea, Captain Ahab, and Darth Vader. But there is also a self-destructive pattern in which the loathing is turned inward; I know both of these scenarios well. When such thought patterns are encoded at a young age, they can be difficult to break. I many ways, a young Anakin Skywalker is the exemplification of this condition. Enduring a traumatic childhood, he longs for compassionate and disciplined guidance, but he is fearful, guarded, and suspicious with a tendency to lash-out at perceived betrayal. His reactions are somewhat of a survival mechanism. Under directed supervision he is able to control his wayward emotions, but after repeated trauma, he reverts to a level of adolescent anger that is explosive and psychotic.

I have long struggled with the question of how to resist such anger. Recently it has been increasingly difficult as a culture of victimhood has arisen; encouraged by a mob mentality on social media. At times, it’s nearly impossible to not identify primarily as a victim. Canadian professor and psychologist Jordan Peterson remarked: “There’s something very pathological about the enhancement of victimization.”

The most effective way to fight against a victim-mindset is the renunciation of all earthly attachments. In the West, St. Francis of Assisi is a model of self-abandonment. According to Thomas of Celano, Francis was reared in a culture of extreme depravity; where, children “when they are weaned they are forced not only to say but even to do actions full of lust and wantonness.” According to the 1956 Edition of Butler’s Lives of the Saints, when St. Francis began to live as an ascetic while repairing the San Damiano Chapel:

“His father, hearing what had been done, came in great indignation to St Damian’s, but Francis had hid himself. After some days spent in prayer and fasting, he appeared again, though so disfigured and ill-clad that people pelted him and called him mad. Bernardone, more annoyed than ever, carried him home, beat him unmercifully (Francis was about twenty -five), put fetters on his feet, and locked him up…”

In the East, a near equivalent is St. Mary of Egypt: a child runaway who imagined a life of independence and pleasure in Alexandria – the 4th Century counterpart to Hollywood in its heyday. She lived a desolate life; perhaps, as someone who tried to reenact previous abuse. At age 29, she was still trapped in this cycle. Yet, during a visit to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem; she had tagged along with some pilgrims from Egypt as a sort of “camp follower,” she underwent a radical conversion. Like Francis, after that, she chose a life of prayer, fasting, and seclusion.

“All who are born in this land hereafter can suffer as we have done.” – Judah Ben-Hur

Another, albeit less radical, illustration is the character of Ben-Hur from the 1959 film adaptation. Judah Ben-Hur is a victim: accused of a crime he did not commit, betrayed by his closest boyhood friend, sentenced to serve as a slave on a galley-ship, his mother and sister are locked away and forgotten inside of Roman dungeon; yet, he survives, and all he has left is hatred and revenge. However, throughout his enslavement, and in the midst of his almost unbearable suffering, a small seemingly insignificant moment remains embedded in his brain: on his way to the galleys, he is comforted by a stranger who gives him water. That’s it. Someone reached out to help him when no one else would – or even cared. Later, when he stands below the crucified Christ – he realizes that the Man was Jesus. Despite the years of cruelty and anguish, he understands that the destruction of the world will not ease his pain.

I had a remarkably similar sort of conversion experience. Like Ben-Hur, I collapsed and laid sobbing with my face in the dirt when a hand suddenly reached out towards me. And, even if for just a couple of seconds, once you are struck blind or silent, such an intense encounter with God instantaneously conveys the immediacy of His presence; for this reason, I can understand why Francis and Mary of Egypt chose to seek refuge in the desert, forests, or inside of a cave. Because, away from the possibility of further abuse, persecution, or torment, only God and the penitent remain.

“Behold, I fled far away, And lodged in the wilderness.” (Psalm 54)

When his homeland was in a state of crisis – suffering from incredibly corrupt leadership (both in the secular and religious worlds) as well as apathy and despair amongst the faithful, God led Saint Joseph out of Israel and into the land of Egypt. Although the exile of the Holy Family was preceded by trauma, the near brutal murder of the Christ-Child, a place of refuge and safety awaited the weary travels after their long journey across the Sinai. While I can presume that Joseph was often anguished because he had to leave all that was known to him, but the surest refuge only exists where Christ resides.

Yet, once the Holy Family returned to Nazareth, they did not go back to a life of ease. The struggles that persist within every family remained – as evidenced by the three-day search of Mary and Joseph for the lost Jesus in Jerusalem. But those who sought the death of their Son were no longer an imminent threat. I imagine that they had peace.

I am not looking for a “safe space” nor a perfect church; but it is impossible to exist, without suffering severe psychological damage, under a constant threat of repeated abuse. Since returning to Catholicism, I have tried to do just that for over twenty years. Solely, the stress has taken its toll on my body and mind; though my faith in Christ has remained strong. But I don’t want to die. And I don’t want to me martyr. Those who died for love of God did not do so because they had been repeatedly groomed, abused, brain-washed, gas-lighted, and driven to self-destruction and suicidality – those are the tragic pseudo-martyrs that the Church is creating today.

Like Francis of Assisi, Mary of Egypt, and the countless hermits, monks, and ascetics – I have chosen to join those who settled in the Saharan deserts, the Umbrian mountainside, or the northern Thebaid. I am following the footsteps of Saint Joseph. Away from a home that is familiar, but corrupt and fraught with danger. One day, I pray I may return.

In the meantime, in the midst of my journey away from the locus of abuse, I have been able to reach a place of forgiveness – for those who abused me, for those who perpetuated the abuse, and for those who refuse to do anything about it. For perhaps the first time in my life, I feel as if those lingering specters of oppression have finally been exorcised. They always followed me; but their presence and power have decreased to near nothingness; because I no longer give them that power or influence. I no longer write to the bishops; I no longer send them e-mails; I no longer hand-deliver letters to their chancery offices; I no longer wait outside after Mass at their cathedrals, to say just a few words to them; consequently, they no longer ignore me; because I am not there. I no longer play the part I used to – that of the lost boy looking for older male guidance and protection.

While I have forgiven everyone for the wrongs that were perpetrated against me, I can not forgive them for the continued grooming, abuse, and manipulation of the vulnerable that has continued unabated in the Catholic Church. I cannot forgive them, because it is not something I can pardon; for the victims of those crimes have not yet spoken out or even realized their own abuse; some of those victims are not even born. I weep for them.

But despite everything, I have moments of real serenity. In the Catholic Church, that experience was an extreme rarity and only took place in a secluded monastic environment. In hindsight, I think I pretended to be happy. I wanted Catholicism to work; it was that same stubborn attitude that kept me in the gay male community for so long; almost to the point of death. In the Church, I was expected to forgive, heal, and be joyful while having to silently witness the perpetuation of abuse. I couldn’t. Seraphim of Sarov once remarked: “Acquire a peaceful spirit and then thousands of others around you will be saved.” In the Catholic Church, I was always angry. Being revictimized. Now, I have peace.

I want to remind you, my brother, and every grown up child suffering from this abuse, that you are loved by someone so much, someone that would change the entire course of history to help you, someone who would die for you.

I was a victim of abuse as an adult, which is far different, but what I know to be true is, that when you finally decide to leave, it’s only because the abuser abandoned any interest in the relationship a long time ago.

All of the special victim groups the Church is “caring for” have always been abandoned, because the Church has the mission to bring Jesus to these people and has brought themselves; their virtue signalling and pride instead.

You, and every victim in these groups were to be the canary in the goldmine to help us see that we were next.

Now where are we?

There is no more of a Church there for me as there is for you. Where is my lord in the Eucharist when I can’t receive Jesus for fear of giving someone the flu. Where is the body of Christ on our tongues healing us from every infirmity? Where are the Cardinals who would defy government to protect and safeguard the sacrifice of the Mass, when Christ, the most abused, is trapped there alone waiting for anyone to love him.

Your lives have purpose, your suffering has merit, the grind of your Calvary is not missed by your saviour. He will rescue his children from the peripheries. You are not alone. We are praying for you. We need you. You are loved.

Amen Joseph! God has released His saving grace in you. So wonderful to read you have found peace. Justified anger is something we all are struggling with as the hierarchy of the church has failed us all. But in the end, God will win and evil will be destroyed. May this Lenten journey continue to swell in your soul the beauty of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.

I was glad to read that you are not leaving the church but will stay and fight. We need you. We parents of homosexual children need you. The world (and most of Christianity) does not support chastity in homosexuals but you do and we need your sweet soul and your example. Continued prayers for you and yours.