“Can we do anything else but trust in God? God calls us to do much, and we have not much time to do it.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose

On the Feast of “The Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple,” I was Baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church (ROCOR.) My journey towards this profound moment perhaps began in earnest during the fateful year of 2018. I had been increasingly tormented within the Roman Catholic Church since I first stepped back into it at age 29. It was 1999, and I had just barely survived ten years of being a gay man in San Francisco. The first priest I spoke with – told me to go back. I didn’t know very much back then, but I knew that would certainly mean my death. So, like the “prodigal son,” I limped home and sat for hours in front of my father’s framed reproduction of “Our Lady of Perpetual Help.” The inexpensive icon was one of the few items that he carried around with him when he was a poor newly arrived immigrant from Sicily. All I remember is the Theotokos looked right at me – and I sometimes looked back. From that day onward – I knew my life would never be the same.

The adult survivors of childhood abuse are often revictimized. Far too often, we push away those who could help us and trust those who are abusive. Instinctively, we gravitate towards the familiar – that which is manipulative and sadistic. From the outside, it seems counterintuitive that someone who experienced trauma would deliberately take part in their own further traumatization. But this cycle of self-destruction subconsciously serves as a means to normalize past abuse – by making it okay. In the process, we surround ourselves with similarly wounded people; those with shared backgrounds and mutual fixations. For the most part, that’s how I ended up in San Francisco as a confused and lonely 18-year-old. Along with thousands of other lost boys, just like me, who were looking for the father, mentor, friend that they never had. Consequently, we essentially used each other. But no one actually had what everybody wanted – a sense of self.

As survivors of trauma, we commonly disassociate from the abuse by fragmenting into various psyches; but more frequently abuse victims will seek refuge within niche sub-cultures. Nowadays, the idea of trauma is often misunderstood as solely pertaining to extreme forms of cruelty or violence. But there are varying gradations of trauma. And not all trauma affects people in the same way; for instance, siblings in the same family, who experience an identical trauma, will frequently be affected in different ways. Some will seek escape inside of a liquor bottle, others in a glass-pipe, or inside of a syringe. A large number find comfort in pornography, fantasy videogames, or sports. Within a life of uncertainly, these addictions and diversions prove to be reliable. We trust our dealers, create shallow relationships, and interact with fellow faceless online players. In the meantime, we ignore or take for granted those closest to us. In the most severe cases, paranoia can control our minds. We are constantly suspicious, focus on increasingly outlandish conspiracy theories, and accuse others of trying to control us – usually through the use of medication; for this reason, thousands of untreated mentally ill people are left living under bridges and in public parks.

When I stood before the front doors of a Catholic Church – that was me: broken, battered, and beaten-down. What I found wasn’t a so-called “field hospital,” but a psych-ward. Like Nurse Ratched, control and power within the Catholic Church is accomplished through fear, manipulation, and psychological persuasion – what some might refer to as “gaslighting.” For instance, the first priest I spoke with upon my return repeated almost verbatim the same words I had heard over a decade before: “God made you gay.” Back then, the predator priest said that to me right before he did it. When I was 18 and I thought destined to live-out the rest of my life in “The Castro,” I felt like I had nowhere else to go. So, I tried to make the best of it. Then, I accepted this genetic, or divine, fate. Later, I would reject it.

The next 20 years in the Catholic Church would be amongst the most difficult of my life. During that time, while I met some unbelievably good men in the Catholic priesthood – and they did much to help save my life, but in the end, even their good deeds became a great source of suffering as I had to powerlessly stand by and watch as they were slowly persecuted and tortured by their bishops – to the point of madness. Their vocations and their lives did not end well. And as I waited to be Baptized, strangely enough, I thought of them – and I cried.

But only about a year or so into my “re-conversion,” I contemplated a life without organized religion. At least in San Francisco, the Catholic Masses mirrored the “Pride” parades that processed up Market Street every June – complete with liturgical dancers waving multicolored streamers, the organ playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” while occasionally one of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence would make an appearance. It’s as if nothing has changed; except the venue. As a Russian Orthodox priest recently said to me, Christianity must remain a constant source of truth and refuge for sinners: “…not something that looks like the hell they just left.”

Suddenly, I just happened to meet some priests who looked unlike those who always seemed to play the part of the inclusive and compassionate “bridge-builder.” These priests weren’t later-middle-aged; they weren’t balding, effeminate, overly gregarious, nor did they wear flowing rainbow-colored stoles. They were young, handsome, and they seemed sincere and devout. And the liturgy they favored looked like the image they presented: traditional, reverent, and serious. Almost as it happened a decade before, I followed them and some dream that I could somehow be made whole through the intercession of men. But like the gay men I encountered in the gay bars, the discos, and online, these men could not make anyone whole. In fact, they were themselves highly fractured; and they were predators. At first, I couldn’t accept it. After years of continual desperation and anxiety, I finally thought that I found someone I was able to trust. I had told them everything – and they used it against me. Claiming that I was seeing were merely the phantoms of my own past. For a while, I believed it. And then I thought I was going mad. Other priests from different religious orders, some of them well-known and prestigious, came and went – they all knew. I thought: “Maybe there was something wrong with me.” Until one of them put their hands on my shoulders – and I was shocked back to my youth; and surprisingly: I fought back.

Afterwards, like I had done before – I limped home. I blamed myself. Only, I remained rather steadfast. Such as the Saints and Martyrs throughout the ages, persecution was part of salvation. I almost immediately glommed onto another priest – who also had some strange sexual predilections. And then another. Yet, this time, the violation proved especially painful. For I met the priest through an online social gathering (chat) group for Catholic men who struggled with same-sex attraction. While I knew this person was a priest – I didn’t know he was an acknowledged predator.

When this priest started to “private message” me, we got to know each other much better; particularly after he began to share his own battles with same-sex attraction. Similarly, I revealed to him the particulars of my life that I only shared with very few people. Then, slowly at first, he started to ask me some odd questions: about my body and my past sexual experiences. He began to talk about a physical relationship he had with a fellow student when they were both in the seminary. Later, we started having conversations over the telephone – and then he convinced me partake in “phone-sex” with him. Afterwards, he invited me visit with him at his out-of-state residence. I thought about. I confided with another member of the chat group. He immediately warned me. He knew about this priest and how he had propositioned other men in the group. They all knew.

Despite this series of encounters with manipulative, grooming, or predator priests, I stayed faithful to the Roman Catholic Church. In retrospect, as an abuse survivor who got re-victimized as an adult, this sort of atmosphere that was permeated with apprehension, danger, and fear seemed familiar. I first recognized this concentration in Roman Catholicism when I was a student of Art History. In Gothic art and architecture with its focus upon the fires of hell, demonic torments, and the Second Coming of Christ, as opposed to the more sober Romanesque before the Great Schism of 1054, worshippers who entered these imposing edifies were usually confronted with a large tympanum (sculptural group over main entrance) that typically featured some rather frightening depiction of hell or the “Last Judgement.” These “catechisms in stone” were meant to instill fear within the viewer; as well as obedience and loyalty to the Church – through which was the only doorway to heaven. By the 14th century, fear and any sort of disloyalty was distilled in the writings of the Roman Catholic St. Catherine of Siena:

“Even if the Pope were Satan incarnate, we ought not to raise up our heads against him, but calmly lie down to rest on his bosom. He who rebels against our Father is condemned to death, for that which we do to him we do to Christ: we honor Christ if we honor the Pope; we dishonor Christ if we dishonor the Pope…But God has commanded that, even if the priests, the pastors, and Christ-on-earth were incarnate devils, we be obedient and subject to them, not for their sakes, but for the sake of God, and out of obedience to Him.”

This sort of endemic brainwashed mentality within Catholicism causes priest sex abuse survivors to keep silent about the violence perpetrated upon them; it also results in a wider contagion of fear and subservience among the laity – who have also been traumatized in the Church. Especially after the “reforms” of the Second Vatican Council, instability, uncertainty, and blatant corruption were nearly everywhere. Despite the proliferation of irreverence, heresy, and depravity in the Church, lay Catholics were still expected to be subservient and differential to the hierarchy. Faithful priests and religious were also blackmailed, coerced, and threatened into continued compliance. The “progressive” Catholic Left simply wanted to assist in the desecration. Although at this time, there were a large number of Catholics who left the Church, those who stayed did so out of fear. The archetypal fear of hell and damnation persisted; I incessantly heard: “There is no salvation outside the Catholic Church.”

For a while, like a number of Catholic seminarians that I knew, I had a strong messianic-complex. I could save the Church. I knew seminarians who endured all sorts of abuse in various seminaries; yet, they remained because they thought (once ordained) they could reform the Church. I was similarly delusional. I also bought into the false idea of the good bishop/bad bishop dichotomy. As a result, I huddled about the “good bishops.” I wrote to them, called them, e-mailed them, attended their Masses, and waited for outside of cathedrals. I was always respectful, but most of them avoided me. Those I did speak with proved largely ineffectual. They were sometimes curious about what I knew; naively I thought because they wanted to do something about it. Later, I found out that they were only “fishing” for information so they could subsequently cover-it-all-up. But from all of them, I had a strong impression of fear and arrogance; many priests I knew were plagued by this same condition. Not coincidentally, at the many “Pride” events where I ministered and outreached to the LGBT community, I also perceived a lot of fear. In spite of the music, laughter, and dancing, the party environment was held together by copious amounts of marijuana, hallucinogenics, and the promise of instant camaraderie. It’s the same sort of decadent giddiness that inundated late-Imperial Rome, the latter days of the British Empire, and the Weimar Republic. When I was once amongst them as a reveler, even though I went through severe bouts of depression verging upon suicide, I never once thought of leaving. Where else could I go? After surviving a childhood of self-doubt, confusion, and loneliness, it was incessantly disappointing, but it was better than nothing. It was better than trying to go it alone. As the contemporary gay slogan goes: “It gets better!” And that’s precisely why I stayed in the Roman Catholic Church for so long. As a plethora of on-line bullies would robotically repeat every time, I shared some doubt about the Church; they would declare in unison: “Where else will you go?”

But I had somewhere else to go. For years, I had heard sort of urban San Francisco urban legends about a former gay intellectual beatnik libertine who once haunted the coffee-houses, bookstores, and theaters of 1950s “North Beach.” As the story went, he eventually tired of his ceaseless exploration of assorted non-Western religious philosophies and converted to Russian Orthodoxy – where he eventually founded a remote monastery in Northern California – where he died at age 48 as Fr. Seraphim. Sounded plausible. After all, it wasn’t any stranger than my own life. Intrigued, I began to read everything I could find about this native-California boy who would become a spiritual inspiration to millions. One day, I retraced this man’s steps through San Francisco and finished my pilgrimage at “Holy Virgin Cathedral.” I’d been there before, but only to admire some of the icons when I was studying Byzantine Art at Berkeley. The place never meant much to me except as a sort of warehouse for curious relics. But as I wandered about the inside of the church, a priest appeared seemingly out-of-nowhere and some kind of “prayer service” commenced. I quickly moved to the back shadows, near the narthex. Immediately, I was swept away by the sanctity and majesty of the entire scene. What Fr. Seraphim would describe as “the mystery of holiness.” It imparted within me a temper of “fear and trembling.” However, I was not anxious. But at peace.

Beginning around 2018, I intermittingly spoke with and contacted several Orthodox priests – from the OCA (Orthodox Church in America) to ROCOR (The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.) I started to attend Orthodox liturgies, primarily at the ROCOR Cathedral in San Francisco, throughout 2018 and 2019. Then, the Covid pandemic happened – and everything screeched to a halt – including my timid exploration of Orthodoxy. At home, I added to my meager “icon corner” and sat for hours before the images of Christ, the Theotokos, and my favorite saints: The Holy Royal Martyrs, Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Egypt. I read a lot; and I never prayed so much in my life. But it wasn’t like going through the motions of vocal prayer as I had done so many times before. It arose more from the heart. The last time this happened was after I crashed-out of the gay male community and tried to figure out what I was going to do and where I was going to go. I was afraid. Yet 20 years of prayer, pain, and suffering separated me from that scared guy. Still, I was very cautious.

I trusted few people. Even my closest friends I regarded with suspicion. In my mind, I thought it was just a matter of time before they betrayed me. According to famed psychiatrist and author Bessel A. van der Kolk: “Being traumatized means continuing to organize your life as if the trauma were still going on—unchanged and immutable—as every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past.” That’s how I lived my life since about the age of 10. It was relentless and exhausting. I was always on high-alert. Every situation was fraught with danger and possible abuse. And it only got worse as I got older. Mainly due to the fact that I was re-abused in the gay male community; and they re-abused as an adult in the Catholic Church. But the latter was more damaging. Although it hurt when a one-night stand left after a couple of hours; after all, I hoped they would become a friend. But its fare less stinging when a stranger treats you cruelly than when its someone you trust. And, while I was suspicious of every priest, I also longed for them to become my “spiritual father.” After all, in confession and spiritual direction – I had to bare my soul to them. I had to be vulnerable in front of them. Something I was never able to accomplish with my own father. But that left me, and many others, open to exploitation. And instead of repeated injury making me stronger, it had the opposite effect – I became increasingly withdrawn and defensive. Therefore, when I arrived to be baptized at a Russian Orthodox church I had been attending, I was incredibly anxious.

After the rather severe Covid lockdown and restrictions were semi-lifted in the state of California, I knew that I wanted to return to church. But I didn’t know which one. The thought of returning to Roman Catholicism was almost unimaginable. Months before, I remember hearing the name of Pope Francis uttered by the priest during the Canon of the Mass – the prayer which contained the highpoint of the Liturgy, when the bread and wine is transubstantiated into the Body and Blood of Christ. At that moment, I would become nauseous. I wanted to vomit. The last time I felt that same way – when I attended the 2018 Los Angeles Religious Education Congress and a priest-presenter claimed that children as young as 7 years old know they are LGBT; he also encouraged Catholic educators to support children in discovering their sexual identity. I said to myself: “This is a how-to-manual for abusing a child.” What happened to me so many years ago, in the darkness, was now allowed to transpire out in open – and at the largest gathering of Catholics in the United States. This was institutionalized grooming. After that day, I never went back to Mass again.

When I entered the Russian Orthodox church and I saw a large steal cistern in the middle of the nave, I became extremely nervous. I started to tremble. My instinct was to turn around and leave. Only, I didn’t. I needed to trust. I needed to trust the priest. And most of all – I needed to trust God.

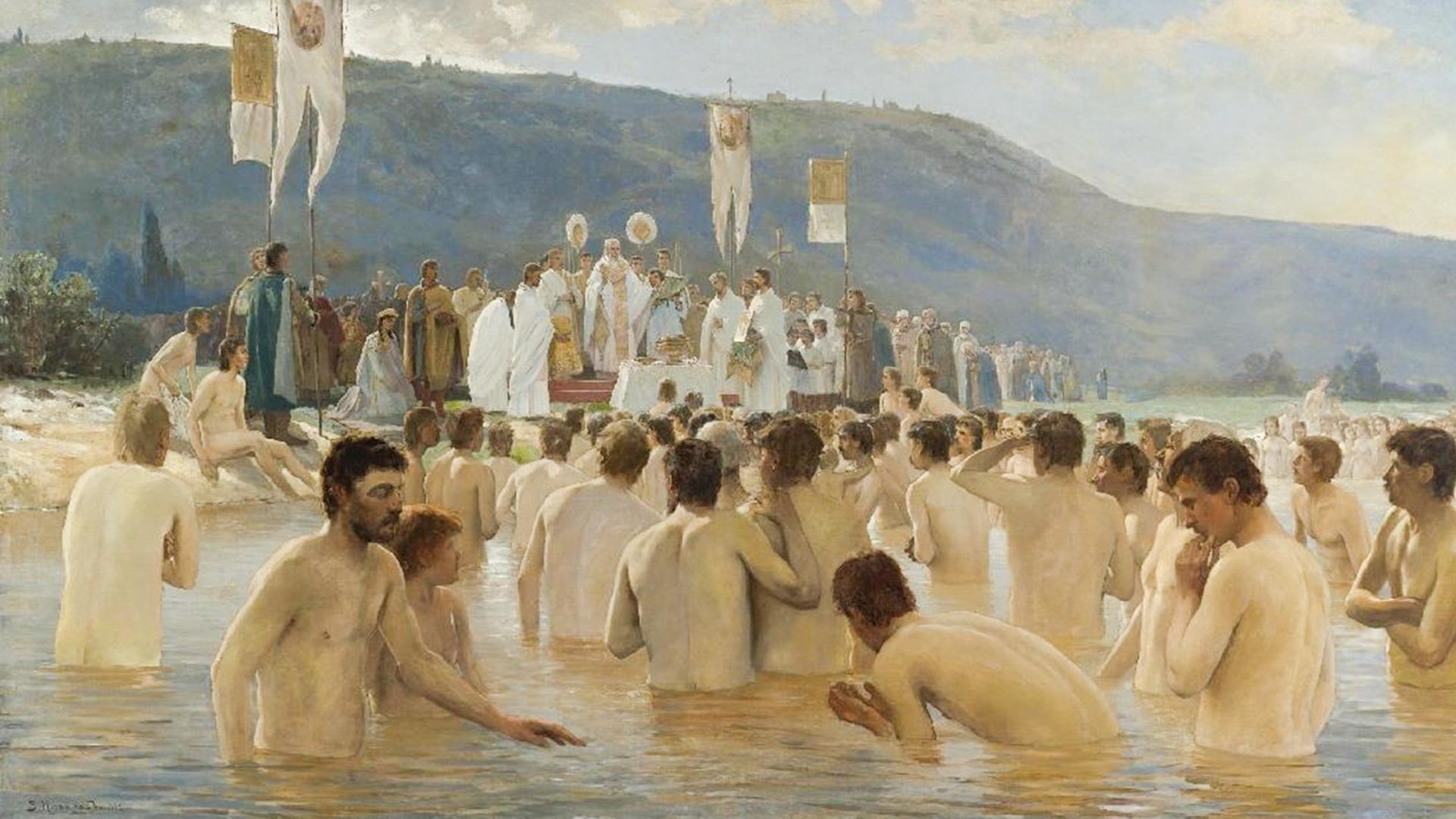

Less than an hour later, I was kneeling in the Baptismal water. The priest placed his hand on my back. I knew what was going to take place – he told me beforehand. But when it was happening – I didn’t like it. I don’t want anyone to touch me – especially a priest. Although there were other parishioners in attendance, I reacted as if I were in danger. So, when the priest tried to gently submerge my face and head into the water – I resisted. He tried again, and I wouldn’t move. I had to let go of this anger, hatred, and rage. I thought: “I must trust.” For the first time in over 40 years, I relaxed just a little bit. And it was frightening. Because, as a child, I learned that when you let your guard-down, even for a few seconds, bad things happen. But it wasn’t bad. I went face first into the water. It actually felt incredibly comforting – like breaking through a membrane that separates us and the world from God. In Baptism, with my hair soaking wet, and the water dripping down my face – it was as if I finally touched the Divine.

“Acquire the Spirit of Peace and a thousand souls around you will be saved.” – St. Seraphim of Sarov

Most remarkably, I wasn’t overwhelmed by anger, hate, and rage anymore. For far too many years, I was endlessly afflicted by an oppressive fury. Part of me believed that this indignation kept me safe. Hostility was like a constant caffeine-drip; I thought it kept me alert and my senses acute. My childhood trauma was exacerbated once I was a teenager and I always looked over my shoulder at school for the next bully who wanted to mercilessly tease me. In the gay male community, where you literally had to watch your backside, my level of anxiety was brought to a new high. As soon as I arrived back in the Catholic Church, I was always prepared for the worst when I walked into any unpredictable situation, the trauma only continued. And my preconceptions about the world were confirmed again.

For a time, I thought I could find safety within the sheltered confines of the Traditional Latin Mass movement (or Trad) in the Catholic Church. For a while, it seemed like “Brigadoon,” a land trapped within an imaginary illusion that was Catholicism in the 1940s and 50s. It’s as of the monochromatic illustrations from “The Baltimore Catechism” had come to life. Yet, as with all insular subcultures, from Masada to Jonestown, they tend to become suicidal. Because within the Trad cosmology, paranoia reigned. It was a culture under siege. Since Vatican II, those who clung to the Latin Mass were increasingly viewed as hopelessly regressive or even subversive. At first, I got caught-up in the customs and the aesthetic of Traditional Catholicism. First of all, there were men in attendance; and they were not all elderly. Oftentimes, these men were the heads of large families. In addition, women were modestly dressed; children were surprisingly well-behaved; and everyone appeared genuinely pious and reverent. Except, anything from outside the community was immediately viewed with mistrust. I was reminded of when “came-out” during the height of the AIDS epidemic; there was little help forthcoming from the medical community; and the government, under the Reagan-Bush regime, were considered complicit in their ineptitude for the deaths of thousands of gay men; conspiracy theories gained numerous adherents. The trauma of an epidemic with a 100% mortality rate, plus the fact that the homosexual subculture attracted men who were already at a loss, created mass-paranoia. In the Trad world, like in the gay male community, real mistreatment and persecution generates fear – and then it all gets heightened. After Mass, conversations always centered upon the latest ecclesial overreach or corrupt use of power. Periodicals, newsletters, and web-sites that catered to Trad groups focused on various “gay” Masses, acts of Eucharistic sacrilege by priests, or the ramblings of dissenting bishops (namely Cardinal Roger Mahony, Archbishop Rembert Weakland, Bishop Thomas Gumbleton). At first, its kind of enthralling: building a you-against-them mentality; and, after-all, we are on God’s side. In addition, at the turn of the millennium, there was an intermittent trickle of good news coming from the Vatican; with Pope John Paul and his righthand-man Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger who were seen as at least sympathetic to the Trad cause; though they both covered-up sex abuse and tolerated dissent. As a result, every syllable relating to the Latin Mass that these two men ever spoke or wrote were microscopically analyzed – this was particularly the case after the publication of Ratzinger’s 2000 book “The Spirit of the Liturgy.”

Rather quickly, I tired of this constant focus on the hierarchy. And after the election of Pope Francis – it became even more fixated. Conversely, the handful of “Traditional” Catholic prelates and priests rise even more to importance. And this is where I truly became disturbed; because Trad Catholics were willing to cover-up for the abuses and excesses of these bishops, priests, and the Trad organizations and religious orders that they oversaw. This was part and parcel with maintaining a certain narrative – in the wake of the 2002 Boston sex abuse revelations, the Trad world was touted as an alternative (the True Church) to the pedophilic scandal plagued Novus Ordo “Church.” In fact, many Trad Catholics began referring to this “Church” as the “Novus Ordo Church” – as if it were something utterly separate from the enclaves of Traditionalism. Yet, Trad communities were only tolerated in a diocese due the blessing of the local ordinary. Who could also take it away.

Trad Catholicism finally kept reminding me of the 2004 M. Night Shyamalan film “The Village.” In the movie, a group of ultra-wealthy men create an isolated medieval-like village within a massive forested and walled-compound. Inside “the village,” family-life is preserved and children are reared in an artificial reality that does not include crime, greed, or any type of hostility. Except, to maintain order – fear is instilled in the villagers by the propagation of a fable concerning a hideous monster which inhabits the woods surrounding the village. These same sorts of scare-tactics I saw employed in the Trad world. While parents should surely prepare their children for what awaits them in a completely secular and anti-Christian culture, a proper upbringing should instill self-sufficiency, not dependency or resentment. For I have been repeatedly told by longtime Trad Catholics, that the attrition rate is very high among kids who were raised in Latin Mass communities.

So, when I decided to go back to church, I immediately discounted the Trad Mass. I no longer wanted to exist under an overlord. During the Covid lockdowns, I immersed myself in the histography of Orthodox (especially Russian) Saints. I drew great strength from the stories detailing their joy for the Lord often in the midst of suffering. I took as my special patron – Fr. Seraphim Rose; a remarkable man who led a remarkable life. I could relate to him. For like myself, I was often a restless wanderer – searching for truth, peace, and his own identity. Within the world – he never found it. Until he started going to the Russian Orthodox Liturgy. I decided, I would do the same thing.

Unlike my experiences with the Trad Mass, which I attended for the first time, after only having known the tacky folk-masses of the 1970s and 80s, the Orthodox Liturgy looked and sounded strangely familiar. But the most foreign aspect was the iconostasis – and the fact that the majority of the Liturgy took place (hidden) behind it. In contrast to the Novus Ordo – where the priest was forced (mainly due to his orientation towards the congregation) to become the focal point of activity – in Orthodoxy, the priest seemed to disappear. I remember a few occasions, when a visiting priest offered the Liturgy, but I didn’t realize this until he emerged from behind the iconostasis. The Orthodox Liturgy is truly consistent. The stability that I sought in Trad Catholicism I actually found in Orthodoxy. In that act of standing semi-still throughout the Liturgy, I truly lost myself…in God.

While Trad Catholicism drew a certain “type” of Roman Catholic or convert – those who reached a crisis of faith due to the chaos in the Novus Ordo liturgy and the collapse of catechetical teaching in parochial schools, not to mention the ugliness of the sex abuse cover-up, Orthodoxy similarly attracted those who had explored a vast number of spiritual avenues that all culminated with a dead-end. In Orthodoxy, I’ve met more American-converts than those who were born into the Faith. But I have always had an appreciation for those who inherited the beliefs of their parents – and persevered. And with the Russian Orthodox, I immediately felt a strong kinship – though not one ounce of Slavic blood runs through my veins. As they were victims of the Russian Revolution, I was a victim of the Sexual Revolution, although these ostensibly dissimilar upheavals essentially had the same philosophical source; as Fr. Seraphim Rose remarked: “Christ is the only exit from this world; all other exits — sexual rapture, political utopia, economic independence — are but blind alleys in which rot the corpses of the many that have tried them.” The Sexual Revolution was the American equivalent of Bolshevism. The counter-culture thought, that through sexual liberation, a fabulous age-of-Aquarius could be ushered into reality. But as witnessed in the Russian gulags, the Sexual Revolution also resulted in stacks of dead bodies; when Western man murdered God, nothing was forbidden anymore. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, in his masterpiece “The Brothers Karamazov,” wrote: “If there is no immortality of the soul, then there is no virtue, and therefore everything is permitted.” Sometimes though I was annoyed with Fr. Seraphim, because he never discussed the particulars concerning his time in the Sodom of San Francisco; but he understood the overarching theology that was buried at the root of this rotten fruit tree. And, that’s what he discussed.

And every generation since then has had to live with the repercussions; for example, my cohort of gay men faced a landscape dominated by an incurable disfiguring disease. Like those Europeans of the Middle Ages, who survived the Black Death, I saw a broad acceptance of bondage and totalitarianism. I first recognized this in the work of the gay-icon Madonna who included BDSM themes within her music and music videos. The flower-power dream of freedom that was born in the 1960s ended with the LGBTQ cult of dogmatic obedience and political loyalty to extremism. This is an essentially Roman Catholic view of the universe – based upon submission. Orthodoxy allowed me to break free from both mindsets and return the true source of holiness and peace; as one Orthodox friend of mine stated: “We do have one shepherd – its Christ.” I’ve spent my life searching for someone, or something, to guide me – when all the time: it was Christ.

Fair criticisms of RCC and Trad movement. However, I think you’d do better to rephrase or edit:

1. Attrition rate children of Trads. Are they better/worse compared to ROCOR?

2. Suicide rates. Is that factual? Do you have stats? I haven’t heard much of this before

Peace be with you, Joseph

Thank Vod you’ve overcome everything and reached a destination. I’ m always amazed how people find the orthodox faith far away from the cradle of Christianity, not being exposed to it from the childhood. It’s a kinda miracle to me . An immensely profound article. Thanks for your braveness to share.

Very moving article. Thank you and congratulations on your baptism! A very happy and holy Christmas.