“He who does not live in Christ…already lives in the Abyss, and not all the treasures of this world can ever fill his emptiness.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose, “Nihilism: The Root of Revolution of the Modern World”

In late-August of 1982, a Russian Orthodox monk lay dying in a Northern California hospital. In the midst of excruciating pain, drifting in and out of consciousness, the monk is fighting his last battle with the devil. Immediately, a band of faithful followers and admirers of this humble man begin a 24-hour vigil for his recovery; from San Francisco to Mount Athos in Greece, candles were lit and prayers were said. Yet, on the morning of September 2, the tall and handsome monk with the greying beard and piercing blue eyes reposed in the Lord. He was only 48 years old.

He grew up in Southern California during the Depression; a highly intelligent boy who would inevitably find that the mainline American Protestantism in which he was raised – proved fundamentally lacking. Like many of his generation, he became a spiritual seeker, eventually moving within the heady space of the “Beats” in 1950s San Francisco. He conversed with poets and gurus, but in the 1960s, when San Francisco became the nexus for experimentation that drew young pilgrims looking for new psychedelic-enhanced experiences and revolutionary ways of expressing themselves, this young man turned to Russian Orthodoxy. When many in the Western world sought to throw off the shackles associated with more traditional modes of thinking and living, an American boy from California embraced an ancient and mysterious faith. His name was Eugene Dennis Rose. In the years after his untimely death, he has become known to the world as Fr. Seraphim of Platina.

Born on August 13, 1935, to Frank and Esther Rose in San Diego California, Eugene was their third and final child. His sister Eileen was 13 years older; and his brother Frank was nine years. Eugene’s father, already in his mid-40s by the time he was born, had a distant although kind and agreeable temperament. But his strong-willed mother was the de facto-head of the Rose household. Eileen remembered a distinct lack of affection from her father and mother: “We were not a demonstrative family.” She continued: “Mother was tough when crossed…and father kept out of harm’s way.”[1]

As a teenager, Eileen left for college, and eventually married at a young age, while Franklin joined the service; essentially, Eugene was raised as an only child. Cathy Scott, Eugene’s niece, described Eugene and the Rose’s domestic life:

“He learned to deal with his mother’s domineering personality in the same way as his father, by sitting quietly and seemingly complacent, yet not necessarily agreeing with the way she saw things, but not arguing with her either.”[2]

Although his father had been raised a Roman Catholic, Eugene was brought up around various Protestant congregations and denominations. From an early age, Eugene was interested in religion, but the Rose’s were not a particularly devout family. During this period of his life, Eugene would accompany his mother (without Frank) to Sunday services; this absence of his father would foreshadow the growing trend in the West, which became significantly more pronounced in the late-20th century, that Christianity was reserved for women and children – not men.

Despite his natural athletic ability, during his boyhood – Eugene could have been described as a bit of a “nerd.” With a distinct humility, and a reserved – perhaps quiet personality, Eugene was a “loner.”

Always studious, and with a keen lifelong interest in classical music, Eugene excelled in high-school. In 1952, when he graduated, he was ranked first in his class. Due to his scholastic aptitude, Eugene received several scholarships. When he decided on a college, he didn’t go very far from home. Located in the suburban city of Claremont, about 30 miles from downtown Los Angeles, Pomona was considered a well-respected private liberal-arts college.

While at Pomona, Eugene chose to surround himself with a small group of academically-focused friends. They were an eclectic bunch of thoughtful “non-conformists.” For many years, Eugene maintained a fairly dedicated correspondence with some of his friends from Pomona; including a lifelong (albeit sometimes distant) friendship with one woman – Alison Harris. Year after graduating from Pomona, Alison visited Eugene at his parents’ house; Alison recognized Esther’s animosity towards her. She spoke with Eugene about it. He said: “She’s jealous.”[3]

While at Pomona, Eugene was a “reader” for a blind student. Sometimes in individuals where one sense is impaired or absent, the other senses or the intuitive perceptions are enhanced; this student said of Eugene: “He was lost in his work. He did not seem unhappy. He seemed very lonely.”[4]

By later historians and commentators, Eugene and his contemporaries were deemed the “Silent Generation” and largely mischaracterized as fundamentally conformist. But within the generation that came of age in the 1950s was an undercurrent of discontent. Born into the Great Depression, the “Silent Generation” became the first American teenagers. After the Industrial Revolution, and the vast migration into urban population centers, although children were no longer required to work on a family farm, the rise of child labor among the poor and working-class in the cities essentially eliminated the idea of a time between adolescence and adulthood. Following the unprecedented post-World War II economic boon in the United States, children had the luxury to simply go to school. Such newfound affluence initiated another mass migration – the middle-class move out of the cities and into planned residential communities. In addition, the availability of automobiles radically transformed traditional modes of courtship and family-life. For the first time, adolescents were able to remove themselves from the ever-present eyes of their parents. A boy didn’t have to court someone’s daughter while seated on a front-porch swing – as the girl’s father watched from the window. Then, since the introduction of “the pill” in 1960, sex became even casual – while the sociological and psychological effects on a societal and personal level were still hitherto unknow. In addition, men were increasingly absent from the home – locked into a car during long commutes in and out of the growing suburbs.

“You’re tearing me apart!” – Jim Stark

The children who came of age in a time of historic prosperity were also the first to question the cultural, societal, and even the spiritual consequences of expanding materialism. But their rebellion seemed somewhat restrained when compared by later generations to the violent upheaval that occurred during the 1960s. One of Eugene’s friends from Pomona described that period in American history: “Those of us who aspired to more than the white picket fence, who sought to be different, did so only at our own peril.”[5]

A major precursor of the turmoil to come appeared in 1955 with the release of the film “Rebel Without a Cause.” Building upon the already growing cultural fascination with the phenomenon of juvenile delinquents, “Rebel” wasn’t a typical B-picture of the genre that included titles such as “Young and Wild,” “Juvenile Jungle,” and “Hot-Rod Girl.” Instead, “Rebel” is a serious exploration of teenage-life, masculinity, and the changing dynamics within families; especially between fathers and sons.

The protagonist of the film, Jim Stark, expertly portrayed by James Dean, is a young man from a middle-class family in Southern California. His mother is extremely strong-willed and dominates her feckless but affable husband. Feeling alienated from his father and his male peers, Jim struggles to discover his place in society – and in the universe; as evidenced by an early powerful scene during a fieldtrip at a planetarium with Jim and his fellow classmates. Afterwards, they fight with switch-blades and race stolen cars over a cliff. No generation in American history has been raised in such prosperity, but many were unhappy and disillusioned. Torn between the conservatism of their parents and their own dissatisfaction with modern life. In some, the rise in material wealth created a desire for an existence with a deeper meaning. And, with mainline Protestant denominations and Roman Catholicism in decline, many didn’t know where to go.

“I had nothing to offer anyone except my own confusion.” – Jack Kerouac, “On the Road”

Between his freshman and sophomore years at Pomona, Eugene spent the summer working at a bookstore in San Francisco. Eugene’s summer sojourn in San Francisco would coincide with the crucial years of 1953 and 1954 when writers and poets such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti traveled to the North Beach neighborhood and the newly opened City Lights Bookstore which became, along with Greenwich Village in New York City, a center for the burgeoning “Beat” movement. The so-called Beats were a group of countercultural nonconformists who rose to prominence in America during the 1950s; although this phrase has come to be identified with a self-indulgent form of narcissism, the Beats wanted to truly “find themselves” during a period when young men and women were expected to embrace bourgeois domesticity and American consumer-culture. Like many of the Beat generation, and similar to a man who he would one day write an entire book about – Blessed Augustine, Eugene was on a quest to discover the truth; later he would write that the study of religion was an “attempt to come in contact with a reality deeper than the everyday reality that so quickly changes, rots away, leaves nothing behind and offers no lasting happiness to the human soul.”[6]

In his personal copy of Augustine’s “Confessions,” Eugene underlined certain passages – primarily those that described Augustine’s former life of sin and later conversion. They included:

“For it was my sin, that not in Him, but in His creatures – myself and others – I sought for pleasures, sublimities, truths, and so fell headlong into sorrows, confusions, errors.”[7]

The coffee-house culture that Eugene encountered in North Beach amongst the Beats would not have seemed unusual to him as his friends in Pomona regularly met at a local coffee-shop near campus; where they discussed everything from modern music to religion and politics; this sort of cultural milieu was revived in the angst of Generation X, exemplified in the semi-psychoanalytic conversations depicted in the film “Reality Bites;” and was eventually gentrified in the sitcom “Friends” at their meeting place “Central Perk.”

Like the Beats, in particular Kerouac, Eugene’s interest in the exploration of an expanded sense of consciousness led him towards Eastern philosophies – especially Zen Buddhism. Eugene would later write of “the restless disillusionment of the post-World War II generation, which first manifested itself in the 1950’s in the empty protest and moral libertinism of the ‘beat generation,’ whose interest in Eastern religions was at first rather academic and mainly a sign of dissatisfaction with ‘Christianity.’”[8]

Again, during the pivotal year of 1953, a former Anglican Priest turned proto-new-age guru named Alan Watts spoke at Pomona. In a sense, Watts was the Timothy Leary of the 1950s. For the next several years, Watts would have a major influence on Eugene. In his 1951 book “The Wisdom of Insecurity,” Watts wrote: “God is unknown to those who know him, and is known to those who do not know him at all.” In 1955, Eugene would attend a summer course at the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco where Watts was a professor. There he met Jon Gregerson – a man he would spend almost the next ten years of his life with.

“In retrospect one can see that the Academy of Asian Studies was a traditional institution emerging from the failure of universities and churches to satisfy important spiritual needs…”[9] – Alan Watts

In 1956, Eugene graduated magna cum laude from Pomona and intended to follow Watts to San Francisco in order to attend the Academy of Asian Studies. His parents were incredibly proud, but their elation proved short-lived. Before Eugene left for San Francisco, his mother discovered a letter between Eugene and Jon, and rightly assumed that they were engaged in a homosexual relationship. As a result, Eugene immediately left for San Francisco. Afterwards, Eugene wrote to a friend:

“I suppose I have not told you earlier of myself because I feared you would regard me a bug, a monster, or merely ‘sick,’ as my parents regard me. I am certainly ‘sick,’ as all men are sick who are ever absent from the love of God, but I regard my sexual inclinations as perfectly ‘normal,’ in a sense I do not as yet understand.”[10]

When Eugene arrived in San Francisco, he and Jon Gregerson moved into a North Beach apartment together. In his new neighborhood, Eugene quickly embraced the rather bohemian attitude of the Beats and the San Francisco intelligentsia.

Beginning with the “Gold Rush,” of the 1840s, San Francisco started to attract adventurers, dreamers, and rugged individualists from across the Unites States and the world. Dubbed the “Paris of the West,” San Francisco had a reputation as a cultural and artistic center in the midst of the wild frontier. As the terminus of the Trans-Continental Railroad, San Francisco was literally the last-stop. The great English novelist Oscar Wilde once remarked: “It’s an odd thing, but anyone who disappears is said to be seen in San Francisco.” With a reputation for experimentation and tolerance, from the Barbary Coast to the Beatniks, it’s not surprising that San Francisco became the fabled city on a hill for a mass migration of disaffected youth during the so-called “Summer of Love” in 1967 and for gay men during the 1970s.

In comparison to the revolutionary attitudes of the hippies, flower-children, and free-love advocates who flocked to San Francisco in the following decade, the somewhat carefree life of Eugene was rather conventional. In his letters to friends from his days at Pomona, Eugene would describe various restaurants, the plays he attended, the movies he saw, the wines he sampled. He became a heavy social and private drinker; occasionally losing his memory after becoming intoxicated. In a letter from 1955, he wrote: “…I reserve the right of being carried away by any conceivable thing, and to defend to the death any absurd notion whatever that my gizzards think they like at the moment.”[11]

“Dammit dammit one DOESN’T save oneself. It’s absolutely impossible and futile. If God, ‘God,’ feels like saving us damn sinners, he will, and there’s nothing we can do about it…” – Eugene Rose (1955)

During this period of his life, his letters often reveal the inner torment of the urban bon vivant. In the 1980s and early-90s, gay American author Bret Easton Ellis brilliantly explored how this world of seemingly limitless freedom and pleasure resulted in addiction, depression, and psychopathology. There is also a certain boredom that dominates their need for an ever-increasing array of leisurely diversions. This materializes in Eugene’s letters through his reoccurring preoccupation with food, dining-out, including the Art-Deco decoration in a restaurant, and various film and movie stars and although this is somewhat unusual in a man, but is indicative of the modern gay male fascination with aesthetics and Hollywood. In a 1956 letter to a friend, Eugene dismissed the fact that his parents were worried about him; he stated: “They are quite concerned about me, which is unfortunate for them, as I am what I am.”[12] His statement predicts the 1970s gay anthem from “La Cage aux Folles” – “I Am What I Am.” When they were living together, Jon Gregerson regularly saw a psychiatrist who wanted to meet Eugene; “…he is already talking of my Oedipus complex,” Eugene remarked.[13] In many of Eugene’s letters written to friends during the 1950s – he appears to be very busy and constantly occupied, but he also sounds anxious; a stark contrast to the peaceful countenance displayed in his correspondences from the 1970s. This difference is partially explained by the maturity and experience that he gained over the years, but as stated by himself – he was also greatly lost during that time. Like so many, he sought something outside of himself. Something that could save him; except it never materialized. Years later, during a lecture series at Platina called “The Orthodox Survival Course,” Fr. Seraphim said: “Many people commit suicide. Many destroy. And what is left for man? There’s nothing left except to wait for a new revelation. And man is in such a state, he has no value system, he has no religion of his own that he cannot but accept whatever comes, as this new revelation.” Later on, when he described those years, Eugene said: “I was in hell. I know what hell is.”[14]

“The world is going mad or driving itself so.” – Eugene Rose (1956)

Through Gregerson, Eugene first became introduced to the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR.) At the time, Gregerson was writing a book that was later printed in 1960 as “The Transfigured Cosmos: Four Essays in Eastern Orthodox Christianity.” In his book, Gregerson discussed the sometimes-unique character of Russian Orthodoxy and the history and devotional practices of Russia – including the hesychasts and the “Jesus Prayer.” He wrote:

“Profoundly aware of evil as evil, the Russian religious consciousness nevertheless sees it as ‘necessary,’ for without it the Good would be meaningless…Even in evil, God can work good, manifesting His grace and His love, bring men to humility and hence to salvation by means of suffering, a suffering caused by their own sinfulness and the sinfulness of others.”[15]

In 1957, Eugene left the Academy of Asian Studies following bitter infighting that resulted in the departure of Alan Watts in 1956. As a result, Eugene began studying for his M.A. in Oriental Languages at the University of California at Berkeley. Eugene’s exit from the Academy occurred when he started to become increasingly disenchanted by his surroundings back in San Francisco. That same year, gay poet Allen Ginsberg’s book entitled “Howl,” published by City Lights Bookstore, drew notoriety after the State of California charged the publishers with obscenity. For its time, “Howl” contained graphic and arguably vulgar words and descriptions; including those of homosexual activity. The State lost their case and the judge’s decision reads like a treatise on relativism:

“There are a number of words used in “Howl” that are presently considered coarse and vulgar in some circles of the community; in other circles such words are in everyday use. It would be unrealistic to deny these facts…life is not encased in one formula whereby everyone acts the same or conforms to a particular pattern. No two persons think alike; we were all made from the same mold but in different patterns.”

By 1958, Eugene had met both Jack Kerouac and Zen Buddhism devotee and poet Gary Snyder. A male acquaintance asked Eugene if he wanted to join him in experimenting with LSD. Eugene soon recognized that the Beat phenomenon was played-out and slipping into commercialization and decadence. He noticed the presence of tourist-voyeurs in North Beach; this predicted the straight onlookers who visited San Francisco’s gay Castro District in the 1970s and then the emergence of heterosexual “allies” at “pride” parades in the 1980s and 90s.

In his “Journal,” dated February 3, 1961, Eugene wrote: “Christ is the only exit from this world; all other exits – sexual rapture, political utopia, economic independence – are but blind alleys in which rot the corpses of the many that have tried them.”[16]

In 1958, Eugene’s retired parents moved to the seaside artistic community of Carmel – located about 120 miles south of San Francisco. Whenever he visited them, Eugene would attend services at the Church of St. Seraphim of Sarov in the nearby town of Seaside. Also in 1959, Eugene received a clumsy but incredibly sincere letter from his father in which Frank Rose tried to comfort and encourage his son who must have been feeling somewhat awkward about sharing his interest in Russian Orthodoxy with his mother who distrusted a religion she knew little about. When Eugene visited his parents with Jon Gregerson, he received a similar reception from Esther as did Alison Harris; Gregerson said: “She regarded me as the one who led him to this evil path.”[17] But Gregerson described Eugene’s father as “a kind man.”

In 1959, Eugene planned to expand a paper he had originally written for Alan Watts, “Pseudo-Religion and the Modern Age,” into a book length treatise on the struggle between Man’s instinctual desire for God and the fallen nature of humanity. The proposed title for the book – “The Kingdom of Man and the Kingdom of God.” While it remained largely incomplete and was never published except for the section on nihilism, this chapter proved to include some of Eugene’s most prophetic and profound statements.[18]

“All good things were formerly bad things; every original sin has turned into an original virtue.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

For the nihilist: There is no absolute truth. The god of the nihilist, Eugene wrote, “…is nihil – nothingness itself – not the nothingness of absence or non-existence, but of apostacy and denial; it is the ‘corpse’ of the ‘dead God’ which so weighs upon the Nihilist.” He added: “The Nihilist wills the world, which once revolved about God, to revolve now about – nothing.”

By 1961, as Eugene completed his Master’s thesis, his attitude towards academia had soured. In a conversion that mirrored the radical conversion of St. Francis of Assisi, Eugene desired an almost total renunciation of this world. He wrote: “Man hungers after what is more than himself, what is more than the world; it is man’s hunger for God, to be a partaker of His nature, that ruins all attempts to make him satisfied with less.”[19]

Later that year, Eugene met former Russian Orthodox seminarian Gleb Podmoshensky. Along with his sister and ailing mother, Podmoshensky immigrated to the United States and eventually settled in Monterey – not far from the home of Eugene’s parents in Carmel. Having spent part of his childhood in German refugee camps, after his father was sent to Siberia by the Soviets, the Latvian-born Podmoshensky had a very different childhood than native-Californian Eugene. But they shared a mutual interest in Eastern Orthodox monasticism and a common struggle with homosexuality; and both of them ceased their endless wanderings once they discovered Orthodoxy.

According to Gregerson, his relationship with Eugene also changed dramatically. Gergerson said: “As he [Eugene] became more and more Orthodox…he did not share my view that one could have a homosexual relationship and remain in the Church. Once he became Orthodox he emphasized the fact that any relationship between us in that sense was over.”[20]

On February 12, 1962, Eugene was received into the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. During the liturgy, that particular Sunday of his Chrismation, the reading included the parable of “the Prodigal Son.” By the end of the year, Eugene met another person who would greatly influence his life: St. John Maximovitch.

Archbishop John Maximovitch (St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco) became Eugene’s earliest benefactor and supporter in the Russian Orthodox Church. Prior to arriving in San Francisco, Russian-born Maximovitch served as the Bishop of Shanghai before the Communist Revolution and then the Bishop of Paris. The diminutive Archbishop was known for his charity and personal piety; but he was also a mystic. This quality sometimes caused even members of his own flock to misjudge and ridicule Maximovitch. Early on, Eugene recognized Maximovitch’s sometimes inexplicable behavior as belonging to an Orthodox tradition known as “foolishness for Christ’s sake.” Consequently, the years Maximovitch spent in San Francisco were often turbulent. An angry faction within the Russian Orthodox community accused him of financial malfeasance, a lawsuit was filed, and it ended-up in court. Although his innocence was proven, following Archbishop Maximovitch’s death, Eugene wrote: “…but this Vladika’s [Slavonic term for bishop] last years were filled with the bitterness of slander and persecution, to which he unfailingly replied without complaint, without judging anyone, with undisturbed peacefulness.”

“Until a man’s earthly life finishes its course, up to the very departure of the soul from the body, the struggle between sin and righteousness continues within him.” – St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco

Eugene often wrote about what he described as a “new Christianity” that was more concerned with social justice than the sanctification and salvation of souls. Eugene wrote: “The tragedy of these times is that men, rediscovering the fact that they require more than earthly bread, turn in their spiritual hunger to what seems to be the ‘renewed’ Church of Christ, only to find there an insubstantial imitation of genuine spiritual food.”[21] His most intriguing early exploration of this problem occurred when Eugene wrote a detailed and lengthy letter in 1962 to the famous Roman Catholic monk Thomas Merton. Years before, Eugene was influenced by Merton’s Augustine-like conversion that he beautifully described in the autobiographical “The Seven Storey Mountain.” But in the 1960s, Merton shifted away from his contemplative emphasis in his writings to a greater concern with political causes, social justice, and the concept of universal brotherhood. In his 1959 article “Christianity and Mass Movements,” Merton wrote:

“…man must give glory to God by living a life that is, in the best and fullest sense, human. Such a life presupposes a reasonable standard of living, a certain freedom, opportunities for education, decent work, and mature participation in the political and cultural life of society.”

Merton supported the radical decision by Pope John XXIII to “open the windows and let in the fresh air.” This concerted turn towards engagement with modernity included an emphasis on ecumenism that ultimately resulted in liturgical experimentation, a deconstruction of Catholic religious orders, and the multiplication of niche theologies – such as liberation theology, feminist theology, and eventually queer theology. The sacred liturgy was transformed into a communal gathering, priests and nuns became activists and social workers, and “the smoke of Satan” entered the Church. In his letter to Merton, Eugene called for a return to prayer, fasting, and Christian tradition:

“…I think, Christians have lost their faith. The outward Gospel of social idealism is a symptom of this loss of faith. What is needed is not more busyness but a deeper penetration within. Not less fasting, but more; not more action, but prayer and penance.”[22]

Ultimately, Merton’s sad ending and death via electrocution while in Thailand, paralleled the sudden decline of the Roman Catholic Church in the latter-half of the 20th century. In his 1965 book “The Way of Chuang Tzu,” Merton wrote:

The man of Tao remains unknown.

Perfect virtue produces nothing.

“No-Self” is “True-Self.”

And the greatest man is Nobody.

This movement away from the Christ-centered practice of mediation towards a Zen-like focus on “nothing” went part and parcel with a vacuum left in the Catholic Church after the Post-Vatican II era that was quickly replaced by false surrogates such as the multiplication of ever narrower definitions of identity and the proliferation of cults in the late-1960s and 70s. By the early-21st century, a large and growing number of Roman Catholic parishes offered Yoga and transcendental meditation classes. The demon in William Peter Blatty’s 1974 novel “The Exorcist” repeatedly said: “I am no one. I am no one.”

As early as 1960, according to Alison Harris, Eugene was already discussing the possibility of becoming an Orthodox priest.[23] He also considered marrying Alison and having a family; but that would necessitate remaining in the world. Only he couldn’t. For Eugene’s vision of his future increasingly included the idea of monasticism. Yet Eugene wasn’t looking to solely escape from this world; a few years later, Timothy Leary would famously coin the phrase: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” By leaving the world – Eugene wasn’t running away, but running towards Christ. In 1959, he wrote:

“To escape from the insanity, the hell, of modern life is all we wish. But we cannot escape!!! We must go through this hell, and accept it, knowing it is the love of God that causes our suffering. What terrible anguish! – to suffer so, not knowing why, indeed thinking there is no reason. The reason is God’s love – do we see it blazing in the darkness? – we are blind. Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy; Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners.”[24]

Eugene’s life would change dramatically when he and Gleb Podmoshensky proposed to Jon Gregerson the foundation of a new religious order – titled the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, and the opening of an Orthodox bookstore near the newly built Holy Virgin Cathedral on Geary Blvd. Jon Gregerson wasn’t interested.

When the Brotherhood’s Orthodox bookstore opened in 1964, it eventually became a focal-point for converts and the curious; of particular interest, in a Church that had a number of Russian-born priests, was the soft-spoken young American. Beforehand, Archbishop Maximovitch had recognized the need for English-speaking missionaries. Therefore, in 1965, Eugene was ordained as a reader – the first of the clerical ranks in Orthodoxy. By 1966, Maximovitch made the innovative decision to institute English-language liturgies at the new Cathedral – with Eugene assisting. Sadly, soon thereafter Archbishop Maximovitch reposed at the relatively young age of 70. Almost immediately, Bishop Nektary Kontzevitch became a friend and patron of the Brothers.

In 1966, Jon Gregerson traveled to the Holy Land and stayed for a while at a Greek monastery. Later, he visited several Orthodox monasteries in the Unites States. When Jon returned to San Francisco, he saw Eugene and visited the Platina property. Then, they parted company. At the time, Eugene wrote of Jon: “Truly his is a hard path…”[25]

While the work at the bookstore continued in earnest, especially with the laborious publishing of “The Orthodox Word,” printed using an antiquated press that required the painstaking process of type-setting, Eugene made his initial plans to move the Brotherhood out of San Francisco and into an environment that more closely resembled the remote woodland sketes of Russia. In his preliminary drafts about daily life at the skete, he detailed everything from the use of hot water to the type of agricultural equipment to be utilized by the monks. By 1967, Eugene was actively looking for a piece of property to purchase. He found one that he loved; located about 230 miles north of San Francisco. With the help of his parents – who provided the down payment, Eugene bought a 80-acre mountaintop parcel near the tiny hamlet of Platina. Then, with the assistance of a couple of lay brothers – Eugene began to quietly build some outbuildings at the future skete. This necessitated Eugene finally learning (in his 30s) how to drive. In the meantime, Eugene continued to operate the bookstore and publish “The Orthodox Word.” But in 1969, Eugene and Gleb Podmoshensky packed up the last of their belongings, included their printing press, and left San Francisco.

“He who has once sensed this fragrance of the desert, with its exhilarating freedom in Christ and its sober constancy in Struggle, will never be satisfied with anything in this world, but can only cry out with the Apostle and Theologian: Come, Lord Jesus.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose, “The Northern Thebaid”

The property in Platina was remote, rugged, and undeveloped. Eugene’s only connection to the outside world was a dirt road that become semi-impassable during the winter. In the isolation of the wilderness, Eugene completed some of his most complex and profound works. A major project for Eugene included translating from the original Russian the lives of the saints from the “Northern Thebaid” – or the northern “deserts.” Like the early Church Fathers, numerous monks and nuns in medieval Russia sought a highly ascetic life in the solitude of the Russian forests. Eugene believed that it was essential for Orthodox Christians to learn about such men and women because the purported “reformers:”

…disparaging the authentic Orthodox tradition, wish to “sanctify the world,” to replace the authentic Orthodox world-view with a this-worldly counterfeit of it based on modern Western thought. The spiritual life of the true monastic traditions is the norm of our Christian life…If we do not live like these Saints, then let us at least increase our far-too-feeble struggles for God, and offer our fervent tears of repentance and our constant self-reproach at falling so short of the standard of perfection which God has shown us in His wonderous Saints.[26]

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, a lone citadel of civilization against the barbarism and chaos of the ensuing centuries were various monastic communities; around such monasteries, villages began to arise and the monasteries became centers of education and trade. Soon after the Brothers arrived in Platina, word quickly spread about the little monastery and the monks who were trying to live like their namesake – St. Herman of Alaska. In the early-19th century, St. Herman, a Russian missionary to Alaska, became a hermit on a desolate island in the Gulf of Alaska. Yet, despite St. Herman’s secluded location – pilgrims began to visit his hermitage, necessitating the need for a small chapel to be built. Nearly the same scenario played out in Platina – at one time, there were fourteen men living at Platina, with Eugene (now Fr. Seraphim) serving at their “spiritual guide.”

“Acquire a peaceful spirit, and around you thousands will be saved.” – St. Seraphim of Sarov

In 1970, Eugene was tonsured as a monk; he was given the name Seraphim after St. Seraphim of Sarov. Though he was not yet ordained as a priest – similar to the bookstore in San Francisco, a steady stream of the wondering and the wayward made their way to Platina. In a few nearby towns, little Russian Orthodox chapels sprung up. These communities primarily comprised Orthodox converts from diverse religious backgrounds, one of them was the future Fr. Alexey Young. A Roman Catholic who first met Eugene at the San Francisco bookstore, Young would be ordained as a ROCOR priest in 1979.

Although Eugene lived a largely hermitic existence, he continued to write and maintain regular correspondence through the mail with his spiritual sons and daughters. His major work during this period was “Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future.” Published in 1975, Brother Seraphim argued that ecumenism amounted to “the self-liquidation of Christianity.”[27] The symptoms of a loss of faith in Christianity, he maintained, resulted in a proliferation of interest in Eastern mysticism, New-Age cults, and the “charismatic revival.” While he sometimes focused upon these trends within the Roman Catholic Church and Protestantism, where their impact was clearly delineated, Brother Seraphim also decried the growing influence of ecumenism and Modernism within the broader realm of Orthodoxy; he wrote: “Orthodoxy has become simply a matter of membership in a church organization or the ‘correct’ fulfillment of external rites and practices.”[28] He added: “The success of counterfeit spirituality even among Orthodox Christians today reveals how much they also have lost the savor of Christianity and so can no longer distinguish between true Christianity and pseudo- Christianity.”[29] And, in his most prophetic voice, he wrote: “It is of the very nature of Antichrist to present the kingdom of the devil as if it were of Christ.”[30]

The questions and daily struggles that were expressed by his sons and daughters in the many letters he received ranged from the deeply theological to the extremely personal; but they were always answered with compassion and humility. To a correspondent who dealt with sexual sins:

“Your battle with ‘demonic fornication’ is not as unusual as you may think. This passion has become very strong in our evil times — the air is saturated with it; and the demons take advantage of this to attack you in a very vulnerable spot. Every battle with passions also involves demons, who give almost unnoticeable ‘suggestions’ to trigger the passions and otherwise cooperate in arousing them. But human imagination also enters in here, and it is unwise to distinguish exactly where our passions and imagination leave off and demonic activity begins — you should just continue fighting.”[31]

On April 11, 1977, Brother Seraphim was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Nektary at Platina. Subsequently, even though there were greater demands made on now Fr. Seraphim’s time, he remained reluctant to travel an extended distance from the monastery. Since moving from San Francisco to the wilderness, except for the occasional trip to visit his mother and his family, he rarely left Platina. Although Gleb, then Fr. Herman, traveled to Europe, including Mt. Athos, the Russian Orthodox Seminary in Jordanville, New York, and around the Pacific Northwest, Fr. Seraphim made just a single extended trip away from Platina to Jordanville in 1979.

Towards the end of his life, Fr. Seraphim spoke and wrote in increasingly prophetic terms. He described the “spiritual vacuum” in the West which made it suspectable to the influence of ideologies and the increasing power of cults. In a rare lecture at the University of California at Santa Cruz, Fr. Seraphim referenced the words of Russian philosopher and former gulag prisoner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; Fr. Seraphim said:

“He [Solzhenitsyn] sees that the system of atheism is not just something Russian, but a universal category of the human soul. Once you have the idea that atheism is true and there is no God, then…everything becomes permitted: it becomes possible to experiment with anything that comes to you, any new inspiration, any new way of looking at things, any new kind of society.”[32]

When the West abandoned God, as Nietzsche described – “God is dead,” the truth also died. Fr. Seraphim wrote: “No one, surely – is the common idea – no one is naive enough to believe in ‘absolute truth’ any more; all truth, to our enlightened age, is ‘relative.’”[33] Today, the ramifications of this philosophy have become clear; as evident in the redefinitions of marriage, gender, and even sex. There have always been debates concerning the philosophical, but now there is disagreement over the empirical.

For some this deconstruction of civilization, and even the body itself, resulted in incredible suffering; amongst gay men, their revolt from absolute truth immediately preceded the AIDS epidemic. For some, a catastrophe can bring forth conversion – a humiliating reassessment of past beliefs. When suffering feels as if it will never end, or when death appears imminent, as was the case with the “prodigal son,” desperate choices are made. In one of his last public address before his death, Fr. Seraphim said:

“When conversion takes place, the process of revelation occurs in a very simple way – a person is in need, he suffers, and then somehow the other world opens up. The more you are in suffering and difficulties and are ‘desperate’ for God, the more He is going to come to your aid, reveal Who He is and show you the way out.”[34]

To those who earnestly sought conversion, Fr. Seraphim gave advice such as this:

“The right approach is found in the heart which tries to humble itself and simply knows that it is suffering, and that there somehow exists a higher truth which can not only help this suffering, but can bring it into a totally different dimension. This passing from suffering to transcendent reality reflects the life of Christ.”[35]

This sentiment is reminiscent of another line that Fr. Seraphim underlined in his copy of Augustine’s “Confessions:” “Our heart is restless, until it repose in Thee.”

Postscript:

Following the repose of Fr. Seraphim, the situation surrounding Herman/Gleb Podmoshensky began to deteriorate rapidly. A few months after Fr. Seraphim, Bishop Nektary died on February 6, 1983. Later that same year, Podmoshensky became associated with a San Francisco-based New Age cult called the Holy Order of MANS. Similar to other esoteric cults that originated from the turbulent cultural milieu of the 1960s, the Order of MANS incorporated a variety of faith traditions from Christianity and Buddhism to Rosicrucianism. But, by the late-1970s, the ever-dwindling group began to turn towards Orthodoxy with the guidance of Gleb Podmoshensky. Rebranded as Christ the Saviour Brotherhood, they were eventually introduced (through Podmoshensky) to defrocked Greek Orthodox priest Pangratios Vrionis. In 1970, Vrionis pled guilty after being indicted for child molestation. Then, Vrionis started his own church and was illicitly consecrated as a bishop. In 1984, Podmoshensky was suspended from the priesthood for “serious moral offenses” and defrocked and expelled from ROCOR in 1988; according to the allegations made by numerous witnesses and survivors, these “offenses” included the sexual abuse of young men. Also in 1988, Podmoshensky would baptize 750 Christ the Saviour Brotherhood adherents and Vrionis ordained several members as priests. From 1994 to 1998, Podmoshensky was living in Alaska with some of his followers near the original site of St. Herman’s monastery on Spruce Island until they were evicted. He died in 2014 at age 80.

In Roman Catholicism, there are notable precedents of religious orders quickly descending towards chaos after the death of its founder – or even while they were still alive, with the two most famous examples being St. Benedict of Nursia and St. Francis of Assisi. The early monks who followed St. Benedict repeatedly tried to murder him – including an attempted poisoning. With St. Francis, the Franciscan brotherhood fell into disobedience and bitter warring factions during Francis’ lifetime. As a result, like Fr. Seraphim in Platina, Francis frequently retreated to his hermetic cell. After his death, the original vision of Francis became corrupted, some of the friars radically departed from Francis’ rule, and the Brotherhood fragmented:

Francis had founded his brotherhood upon the three ideals of poverty, simplicity, and humility. So long as he was alive, any attempt to depart from these ideals could be resisted for his influence and authority was very strong. But after his death things were different.[36]

Epilogue:

“’…with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.'” – Evelyn Waugh, “Brideshead Revisited”

In many aspects, as a young man, Fr. Seraphim was the American mid-century middle-class equivalent of Sebastian Flyte. The ne’er-do-well homosexual son of English Catholic aristocrats who sought to escape some unseen and haunting memory of the past, Sebastian Flyte drinks and debauches himself to near self-destruction across pre-World War I Europe. To his great consternation, he can never fully escape the fundamental truths he acquired from Christianity – in his case, Roman Catholicism. His ethos is summarized in a misquote of Augustine: “Who was it used to pray, ‘Oh God, make me good, but not yet’?” During a Q & A session after his 1981 lecture at UC Santa Cruz, Fr. Seraphim said: “…once you accept the revelation, then of course you are much more responsible than anyone else. A person who accepts the revelation of God come in the flesh and then does not live according to it – he is much worse off than any pagan priest or the like.”[37] When they were both students at Pomona College, Alison Harris remembered when: “He [Eugene] would get drunk and would lie on the floor, pounding it with his fists, screaming at God to leave him alone.”[38] Like Sebastian, Eugene could never run away completely from God. The Christian prototype for the headstrong truth-seeker remains Augustine: “I wandered with a stiff neck, withdrawing further from Thee, loving mine own ways, and not Thine; loving a vagrant liberty.” Yet, in this quest for the illusion of absolute autonomy through the guise of inquiry, true happiness is never found. One of the many afflicted souls in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel “The Demons” lamented the fact that: “God has tormented me all my life.” It’s not simply that the Christian is merely obligated to fulfill their commitments to Christ (in their daily life) but is compelled to do so – if they refuse, their existence will become a misery.

“One man can be lost in an infinite universe. We don’t know what’s going on, because the sun has gone out. God is gone. And of course, if you don’t believe in God, the world becomes a very miserable place. Indeed, you don’t know where you’re going, what you’re doing, because God gives meaning to everything else in life.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose, “The Orthodox Survival Course”

It could be argued that the life of Fr. Seraphim might serve as a sort of Rorschach test. Different people come to different conclusions about Fr. Seraphim’s life. For some, he was a restless wanderer searching for the truth; for a few, he was a conflicted gay man living in a less accepting time; still others see him as a great religious thinker and writer, a prophet, even a saint; while some view him as a heretic who wrote about UFOs and “aerial toll houses.” Even the books written about him are often conflicting and contradictory. Originally published in 1994 as “Not of This World: The Life and Teaching of Fr. Seraphim Rose,” the author Hieromonk Damascene, the superior of the St. Herman of Alaska Monastery in Platina, never even mentions the pivotal 1956 letter in which Eugene revealed his homosexuality.* It was not until the year 2000, when Cathy Scott, the niece of Fr. Seraphim, wrote her own biography of her uncle, that a fuller picture of Fr. Seraphim’s life was available. But as exhaustive (at over 1000 pages in the later editions) as Hieromonk Damascene’s work was, in the end – it’s an odd exercise in attention to detail and a simultaneous avoidance of the obvious. Although the amount of exhaustive research and the interviews in the book are invaluable, what made the stories of St. Augustine, St. Mary of Egypt, and St. Francis of Assisi so compelling to future generations were their often-dramatic conversions. Despite everything, some 40 years after his death – the life and labors of Fr. Seraphim continues to inspire.

“You know how I suffered for my careless and thoughtless life; but you do not know how I have been blessed in my unknown pilgrimage and filled with joy in the fruits of repentance.” – “The Way of the Pilgrim”

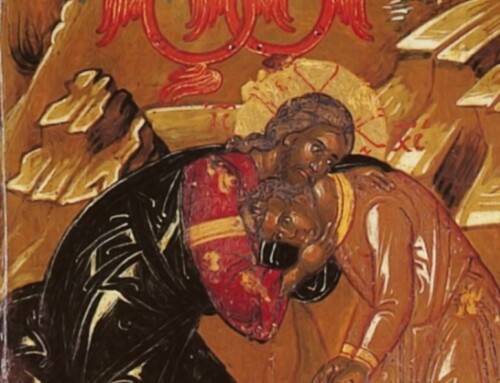

In the 2,000-year history of Christianity, there are numerous hagiographies, biographies, and legends surrounds various saints and holy men and women who underwent radical conversions. The temptations endued by many of them have become well-known, even to non-Christians; for example, The Temptation of St. Anthony has been depicted in numerous artworks. However, the details of such temptations, let alone the particulars of a saint or holy person’s sexual desires or proclivities, are rarely mentioned; an exception would be St. John the Long-Suffering. Yet, the examples set by these holy men and women have given hope to those who are in the midst of a similar spiritual battle. But for those who experience same-sex attraction, there are few Christian role models to follow for guidance and inspiration; despite the revisionism of contemporary LGBTQ historians such as John Boswell, this is due to the fact that an exclusively “gay” public identity was almost non-existent (with rare exceptions like Oscar Wilde) in the Western world – including during antiquity.

Yet, a series of secular gay saints, such as Harvey Milk and Matthew Shepard, were canonized by LGBTQ activists in the late-20th century; even reaching “iconic” status in Byzantine-style icon paintings. In addition – the date of the Stonewall Riots became an American high-holy day; then expanded into the entire month of June. But in his work on nihilism and the book “Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future,” Fr. Seraphim warned about a “vacuum” of nothingness in modern society that would be filled by “false religions.”

“If you want to overcome the whole world, overcome yourself.” – Fyodor Dostoyevsky, “The Demons”

Perhaps, what is most remarkable about Fr. Seraphim is that in many ways he was a man of his times, but also a man who completely transcended the age he was born into. We are all at least partially formed by our environment; maybe none more so than “gay” men. British-American neuroscientist Simon LeVay, who has spent most of his career trying to locate a “gay” genetic determinate for homosexuality, in his book “Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why: The Science of Sexual Orientation,” wrote: “gay men do indeed describe their relationships with their mothers as closer, and their relationships with their fathers as more distant and hostile, as compared with how straight men describe these relationships.” Even Richard Isay, a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and gay-rights advocate, who was instrumental in changing the way the mental health field approached the gay community, had to admit that:

The majority of gay men, unlike heterosexual men who come for treatment, report that their fathers were distant during their childhood and that they lacked any attachment to them. Reports vary from “my father was never around, he was too busy with his job,” to “he was victimized by my mother, who was always the boss in the family,” to that of the abusive, unapproachable father.”

Eugene’s sister Eileen remembered: “If there was a favorite child, it was Eugene, because he always tried hard to do what was expected and did not cross Mother. He was a good boy.”[39] In addition to the presence or lack of involvement from a distant or disinterested father, this mother-son dynamic is typical with many young men who later identify as gay. For this reason, there is much about Fr. Seraphim’s early years – his family relationship, loneliness, and search for meaning, that resonates with those who came from a similar background. In several ways, the lives of many gay men mirrored that of a young Eugene – their paths continually intersected throughout San Francisco, but separated by over a decade; for it wasn’t until the 1970s that large numbers of gay men from throughout the United States began to move Westward towards the fabled city by the Golden Gate. They were drawn there for probably the same reasons that attracted Eugene to San Francisco: a city with a reputation for tolerance; a community of societal misfits; and a philosophical and artistic atmosphere that encouraged exploration and experimentation. But, like the gay men who arrived in San Francisco after him, the promises of the sexual revolution, the free-love movement, and gay liberation resulted, not in a utopia, but in the stark reality of mental illness, drug addiction, and sexually transmitted diseases. As early as 1960, Eugene predicted the eventual outcome:

“‘Sexual freedom:’ this coupling of words that represent totally incompatible realities (since ‘sex’ as practiced today is slavery) is but another instance of that modern incompetence to do anything but follow one’s passions and accept whatever vulgar slogan justifies this aim.”[40]

Here, Eugene predicted the early-21st century mantra “Love is Love” that was effectively utilized by same-sex marriage activists before the legalization of gay marriage throughout the United States in 2015. The year prior, in 1959, Eugene described what he found to be “the insanity, the hell, of modern life.” Probably in no other population has the contrast between the promise of modern life and the reality been more evident than among gay men. In the 1970s, symbolized by the gay anthem “Go West” by The Village People, gay men were promised paradise if they were only brave enough to “come-out.” While in the 1950s, when Eugene was among some of the first American men to live openly as homosexuals, the process of self-declaration was far more subtle and subdued – like in Eugene’s case, it often meant only coming-out to family and friends. Many others remained in the closet. In the 1970s, everything changed – homosexuality had gone mainstream: from television shows like as “Soap” and “Three’s Company” to David Bowie and Sylvester, pop-culture created a glamorous image of gay men who appeared to unendingly drift from Studio 54 to West Hollywood. Yet, by the 1980s, the fantasy had turned into a nightmare – embodied in the hundreds of thousands of gay men across the United States who would perish from AIDS – with the first cases appearing in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco in 1981; which would be the last full year that Fr. Seraphim was on Earth.

“The world has proclaimed the reign of freedom, especially of late, but what do we see in this freedom of theirs? Nothing but slavery and self-destruction!” – Fyodor Dostoyevsky, “The Brothers Karamazov”

“Slogans,” nor the laws that followed them, have brought about well-being; in countries with a long-standing social and political history of gay inclusion and legal protection, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, mental illness (namely suicidality) remains higher among gay men. This profound and sudden awareness of disappointment and loss has led to a wider sense of anger and resentment; in the modern age, this cynicism fills social media and eventually spills out with violence on city streets; but even in these moments of torment, Fr. Seraphim saw hope:

“Disillusionment, in a sense, is preferable to self-deception. It may, if taken as an end in itself, lead to suicide or madness; but it may also lead to an awakening.”[41]

According to Fr. Seraphim: “Never has such disorder reigned in the heart of man and in the world as today.”[42] After years of searching, Eugene realized that: “Christianity is, supremely, coherence, for the Christian God has ordered everything in the universe, both with regard to everything else and with regard to Himself…”[43] Yet, in 1956, when Eugene revealed his homosexuality in a letter to a friend, he regarded his “sexual inclinations as perfectly ‘normal.’”[44] But, near the end of that year, in a letter to the same friend, Eugene’s attitude seemed remarkably less confident and noticeably darker: “Among the damned, I feel there is no hierarchy…I am not to be emulated or admired, and condemnation is just.”[45] By Easter of 1957, Eugene was fully immersed in Russian Orthodoxy; he wrote: “Every day this week is a feast day…After this, the outside world is dreary indeed. Everywhere people are only pieces, fragments of a broken whole.”[46] As many gay men discovered, whatever ghosts that haunted them before, were still hovering about many years after they chose to no longer deny or hide their sexual orientation. In some men, this moment of uncertainty can cause a crisis; and, as Fr. Seraphim believed, this can “lead to an awakening.” Then, sometimes the “prodigal son” will begin his journey homeward.

“Eugene renounced not only his past, but everything, even himself. He gave everything over to God.”[47] – Alison Harris

Eugene could have had a long and distinguished career in academia; he could have remained in a same-sex relationship; he could have had a very different life. He also could have made some of the details about his past personal experiences a larger part of his writing, but he didn’t. Instead, he chose to follow another path. In Platina, when he wasn’t working outside on the property or inside the chapel, he was in a small isolated cell (or hermitage) that he built for himself out of wood. It was unpainted, uninsulated, and freezing cold in the winter and sweltering in the summer. There, Fr. Seraphim would write, type, and pray. Later he almost died inside of it. When the fame of St. Francis of Assisi reached its zenith during his lifetime, and the brotherhood he founded began to expand and become plagued with internal strife, Francis fled to the Tuscan mountains where he built a small log-hewn cell. But like Francis, despite their personal desire for seclusion, a diverse group of people were drawn towards Fr. Seraphim: the deceived and the desperate, the learned and the lost, and those who were searching for a comfort, solace, and the truth. According to those who encountered him, Fr. Seraphim was a kind and sympathetic man – especially towards the suffering. For he had once been one of them. Although he was a great intellect, Fr. Seraphim’s advice and observations were often deceptively simple and direct. In a letter to Alexey Young, Fr. Seraphim shared some pastoral recommendations concerning a young man struggling with addictions and homosexuality who recently visited Platina:

“The only answer to this is to demand a strict account from him of those things for which he is responsible. I emphasized to him that such things are very important for him – more important than a prayer rule, etc…the best thing you can give him is a sense of the reality of everyday life for normal people.”[48]

Basic, but profound. This is reminiscent of the straightforward counsel, like “Clean up your room!” and “Stand up straight with your shoulders back,” offered to directionless young men by Canadian psychology professor Jordan Peterson. This also reveals what many Christian churches, including Roman Catholicism, got wrong when ministering to those with same-sex attraction – they created LGBTQ support groups, “pride” liturgies, and even queer theology; as a result, certain men, women, and young people are identified by a sexual orientation. In 1960, Eugene wrote: “Just as modern man has been made into a ‘political animal,’ so has he been ‘sexualized.’”[49] In a “Journal” entry from 1961, Eugene recorded the following: “We must be crucified personally, mystically; for through crucifixion is the only path to resurrection…And we must be crucified outwardly, in the eyes of the world; for Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world, and the world cannot bear it, even a single representative of it, even for a single moment.”[50] This “dying to self” on the Cross results in what St. Maximus the Confessor described as an “identity by grace” – through which, we are redeemed. Fr. Seraphim transcended all temporal identifications with sexual orientation, and as a result – he himself became transcendent.

“The noble Joseph, when he had taken down Thy most pure body from the Tree, wrapped It in fine linen and anointed It with spices, and placed It in a new tomb…” – Troparion of Holy Saturday

When Fr. Seraphim lay dying in a hospital, some of his spiritual sons and daughters gathered about his bed to pray. At one point, they began to sing “Noble Joseph,” one of his favorite hymns. And he began to cry.

At the end of his life, Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti labored solely on his last incomplete work – “The Rondanini.” The sculpture depicts Michelangelo as Joseph of Arimathea, cradling the body of the crucified Lord. In a slightly earlier version, the head of Joseph is clearly a self-portrait. The suffering of Michelangelo, for he too struggled with homosexuality, is joined eternally to the Passion; gone forever are the images of beautiful male bodies that preoccupied him throughout his life and career. Nothing remains except Christ, the Cross, and love. Eugene understood this; even before his conversion to Orthodoxy. In 1961, a year before he would be received into the Russian Orthodox Church, during a severe illness with symptoms eerily similar to the ailment that eventually killed him, Eugene wrote:

“Why do men learn through pain and suffering, and not through pleasure and happiness? Very simply, because pleasure and happiness accustom one to satisfaction with the things given in this world, whereas pain and suffering drive one to seek a more profound happiness beyond the limitations of this world. I am at this moment in some pain, and I call on the Name of Jesus – not necessarily to relieve the pain, but that Jesus, in Whom alone we may transcend this world, may be with me during it, and His will be done in me.”[51]

- [1] Damascene. Father Seraphim Rose: His Life and Works. Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2010. p. 6.

- [2] Scott, Cathy. Seraphim Rose: The True Story and Private Letters. Salisbury, MA: Regina Orthodox Press, 2000, p. 13.

- [3] Damascene, p. 109.

- [4] Scott, p. 20.

- [5] Ibid, p. 56.

- [6] Damascene, p. 36.

- [7] Rose, Seraphim. The Place of Blessed Augustine in the Orthodox Church. Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2007, p. 104.

- [8] Rose, Seraphim. Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future. Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2018, p. 52.

- [9] Damascene, p. 51.

- [10] Scott, p. 72.

- [11] Ibid, p. 65.

- [12] Ibid, p. 101.

- [13] Ibid, p. 103.

- [14] Damascene, p. 59.

- [15] Gregerson, Jon. The Transfigured Cosmos: Four Essays in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2020, p. 44.

- [16] Damascene, p. 95.

- [17] Scott, p. 73.

- [18] Later published as Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age.

- [19] Damascene, p. 126.

- [20] Scott, p. 161.

- [21] Damascene, p. 246.

- [22] Scott, p. 181.

- [23] Damascene, p. 111.

- [24] Damascene, p. 98.

- [25] Letters from Father Seraphim: The Twelve-Year Correspondence between Hieromonk Seraphim (Rose) and Father Alexey Young. Richfield Springs, NY: Nikodemos, 2001, p. 268.

- [26] Kontsevich, I M, and Seraphim Rose. The Northern Thebaid: Monastic Saints of the Russian North. Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2004, p. xviii.

- [27] Orthodoxy, p. xxv.

- [28] Ibid, p. 182.

- [29] Ibid, p. 189.

- [30] Ibid, p. 188.

- [31] Damascene, p. 806.

- [32] Rose, Seraphim. God’s Revelation to the Human Heart. Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1987, p. 32.

- [33] Nihilism, p. 12.

- [34] God’s Revelation, p. 41-42.

- [35] Ibid. p. 42.

- [36] Moorman, John. A History of the Franciscan Order: From Its Origins to the Year 1517. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 94.

- [37] God’s Revelation, p. 47.

- [38] Damascene, p. 49.

- [39] Scott, p. 196.

- [40] Damascene, p. 151.

- [41] Nihilism, p. 110.

- [42] Ibid, p. 107.

- [43] Ibid, p. 104.

- [44] Scott, p. 72.

- [45] Ibid, p. 115.

- [46] Ibid, p. 125.

- [47] Damascene, p. 200.

- [48] Letters, p. 195.

- [49] Damascene, p. 157.

- [50] Ibid. p. 159.

- [51] Ibid, p. 163.

*However, Hieromonk Damascene does reference some of the contents of this letter in “Father Seraphim Rose: His Life and Works.” See pg. 58. Damascene quotes Seraphim Rose (then Eugene Rose) as writing in that letter: “I am certainly ‘sick,’ as all men are sick who are absent from the love of God.” This excerpt was a direct allusion to Eugene’s homosexuality.

It’s nice to hear from you again.

I think I saw this person on twitter a few times. This is a very remarkable story he sounds like a very holy man. It’s nicer hearing stories such as these, as sometimes it is hard to believe God wants to save everyone, with so few models of conversion….?

Joseph, thank you so much for investing your time and energy in this work you have taken on.

I want to take this opportunity to pose a question that I’ve asked you and others before:

Rather than speak of “same-sex attraction” (which doesn’t have to be of a sexual nature and is usually just called “attraction”), why not use the phrase “unnatural sexual attraction” to distinguish it from natural sexual attraction?

All of us, when we are young, are attracted to others of our same sex, and often repulsed by people of the opposite sex. Boys are learning to be boys and girls are learning to be girls and all of us are attracted to what appear to be “good models” of things (athletic skill, intelligence, physical appearance, various talents, etc.) that simply attract us. God only knows why?

Anyway, I wonder if this purely NATURAL attraction gets tangled up with our awakening sexual awareness as we approach puberty and rather than be corrected by kind and loving adults it gets fortified by a deeply confused culture that really doesn’t know better.

Your thoughts?