“The greatest paradox of our life is that while we all instinctively strive for happiness, most of the time we are unhappy and dissatisfied even when no danger threatens us. Philosophy is helpless in satisfactorily clarifying the reason for this paradox. The Christian faith, however, explains that the reason for our dissatisfaction and dark feelings lies within ourselves. It results from our sinfulness – not only from our personal sins but also from our very nature that is marred by the primordial sin. Sinful corruption is the main source of our grief and suffering.” – Bishop Alexander (Mileant) of Buenos Aires and South America

In 2018, when I first started to regularly attend the Orthodox Liturgy at a Russian Orthodox Church, there were some aspects of it that seemed very familiar, and other parts that were incredibly strange to me. Since I had been attending the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) in the Roman Catholic Church for the past 20 or so years, I was used to following the Liturgy with a “missal.” With the TLM, most of the mass is spoken in Latin, with the Epistle and the Gospel sometimes translated into English. At the Russian Orthodox Church, the majority of the spoken parts were in Slavonic. Like Latin, a language that I neither knew nor studied. But over the years, while regularly attending the TLM, I slowly learned certain Latin words and phrases by rote. Sometimes, I could understand where the priest was in the mass by the inflection of his voice. Occasionally, I did not even need a “missal.” By then, I knew by-heart the “Confiteor” and the “Creed.” But Slavonic was different. Primarily because it came with its own alphabet. It was even more mysterious than Latin. But there were other certain “traditions” that were inherent in Russian Orthodoxy that I could not learn about in a “missal.” I had to experience it.

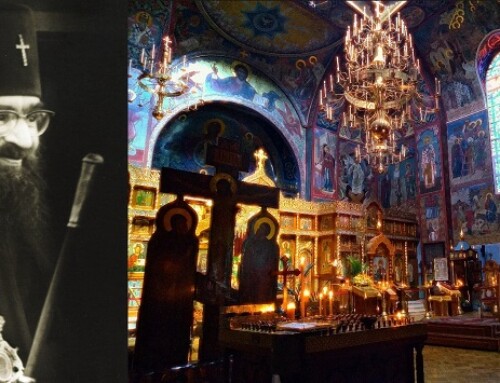

However, many sections of the Orthodox Liturgy were not at all foreign to me. Although, if I had arrived at Orthodoxy, directly from the Catholic Novus Ordo, I would have been greatly dismayed by the lack of female ministers, guitar strumming, and hand-holding. Like the TLM, this was a reverential and solemn Liturgy, but with less of an emphasis on the priest. In the Orthodoxy Liturgy, the priest is certainly indispensable, but he is not under a constant spotlight. In fact, for the much of the Liturgy, he literally disappears from the view of the laity – behind the iconostasis. In fact, when I first started to attend the Orthodox Liturgy, and was not particularly familiar with the priest’s voice, I was surprised, midway through the beginning, when another priest emerged from behind the iconostasis. Priests become somewhat interchangeable; unlike the propensity in Catholicism, even within the TLM world, for priests to become pseudo-celebrities; known for their personal piety or impressive sermons. Orthodox sermons (or homilies) tend to be short compared to their Catholic counterparts; at the TLM, I regularly had to endure a 30-minute treatise that oftentimes felt as if it were being expounded in order to impress some Thomistic subsect of the present lay community. But the short little lessons from the Orthodox priests were highly practical and relatable, yet grounded in the Orthodox mystical tradition.

Most of all, I soon realized that the Orthodox Liturgy is a profound moment of prayer, stillness, and tranquility. It’s difficult to describe. Since childhood, I have been fascinated by mountains and mountaineering. Thankfully, living in California – there are numerous opportunities to climb mountains well over 6,000 feet. On those rare days, when you have scaled higher than most of the casual day-trippers, and the wind is almost non-existent, I attained a sense of peace that is both momentary and seemingly eternal. I always longed for that incredible feeling of serenity. Most of my life, I never had it. Like the prodigal son, I went in search of something. Though ended-up in the same pigsty. I found out that absolute freedom eventually leads to enslavement. Yet, on that mountaintop, in those precious seconds – the physical, mental, and spiritual worlds came together and existed in synchronicity. During the Orthodox Liturgy, I got back to that place once again.

“Bring my soul out of prison, that I may praise Your name; the righteous shall surround me, for You shall deal bountifully with me.” – Psalm 142

As I became more and more familiar with the Orthodox Liturgy, I also began to notice similarities between Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy in terms of the Sacraments. Although both Baptized with water, Orthodox Christians are fully immersed. For an adult, like myself, this can be a somewhat unsettling, but ultimately liberating experience. As for the Eucharist – reception of both species was not unusual to me, but the use of leavened bread was; including the tradition of infants receiving Communion. The former I slowly got used to; the latter did not affect me as I do not have children. Perhaps the most disconcerting divergence from Catholic tradition was the frequently of “Confession” in Orthodoxy. At least once a week – before receiving Communion on Sunday. Ideally this takes place during the Saturday Vespers when the priest is available for Confession – and then the penitent may receive Communion the following morning during Sunday Liturgy. In Novus Ordo Catholicism, attendance at church on Saturday evening (during a Sunday Vigil) precluded going to mass again on Sunday. But as I learned, the Orthodox Saturday Vespers was a separate Liturgy. There are several readings from the Psalms. Therefore, it is a penitential, but hopeful service. And, because it’s usually nighttime or at least dusk, the flickering of the candles reflecting against the gold background of the icons creates a wholly transcendent experience that I have never gotten tired of.

In Roman Catholicism, Catholics should partake in the Sacrament of “Penance” (or reconciliation in the Novus Ordo Church) at least once a year, or (ideally) before receiving Communion if one is aware of a mortal sin. For the majority of my life, I only went to Confession when told to do so by the teachers and nuns at the Catholic schools I attended from kindergarten to the 12th Grade; this usually took place around Easter and before Christmas vacations; although I never remember Confession being made available in Catholic middle or high school. Otherwise, I never went. In my mind, Confession and the Eucharist were not related. This might have been entrenched within me, because as a child – I inexplicably received First Communion (at about age 7) a full year before I ever went to Confession. When I finally returned to Catholicism as a 29-year-old, I didn’t know much, but like the prodigal – I instinctively understood that I needed to ask for forgiveness. So, I eventually got in line next to the confessional inside a local parish where I knew that the priest was a good man. It was all incredibly dark and foreboding – in particular, stepping into the shadowy confessional “box” – with the priest hidden behind a semipermeable screen; but far more disturbing were the creepy “reconciliation rooms” at the vehemently Novus Ordo parishes – in which the penitent was forced to sit across from a priest in a closed-door closet. But the anonymity of the confessional caused a lot of the men I knew to become serial masturbators – as they frequented the Sacrament like a car-wash; rinsing off the mud and mire, receiving Communion on Sunday, then proceeding to go off-road once again; while the convivial nature of the reconciliation room created an environment too conducive to chit-chat – usually between the priest and a middle-aged female. Many a Saturday, I waited for 20-30 minutes (as the next person in line) while a woman spent half of the 45 minutes the priests allocated to hearing Confessions. However, for the most, I tried to “confess” only to one decent priest who I knew. He recommended monthly Confession. Which kind of seemed like a lot.

“A grave sin destroys the soul, and renders it unfit for spiritual blessedness.” – St. Barsanuphius of Optina

When I started attending the Orthodox Liturgy, I was perplexed by someone “huddling” with a priest in a corner of the church. After what appeared to be a brief conversation, the priest placed part of his vestment over the shoulders of the person – and made the Sign of the Cross above their head. I assumed this was some form of Confession. But I asked myself: Why is this taking place out in the open? Can others hear? Where is the Confessional? Since becoming a sort of Orthodox “inquirer,” I tended to hang-out in the back of the church, watch, and try to figure-out what was going on. First, without pews in many Orthodox churches, especially within the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), people tend to purposefully walk about the church – venerating the various icons before the Liturgy began; although they try to avoid the area where the priests heard Confession. Secondly, Confessions appeared to take no more than 5 or 10 minutes. Lastly, the more I observed, I started to appreciate the openness of Confession in Orthodoxy. As a survivor of childhood sex abuse, I liked the fact that I wouldn’t have to be shuttered inside a tiny room with a priest. This also lifted the aura of shame and secrecy which permeates the Sacrament in Catholicism. Looking back, I sometimes wonder if the Catholic emphasis on self-punishment and concealment in Confession contributed towards a strange willingness to cover-up my own abuse in the Church. While in Orthodoxy, there is certainly a repentant aspect to Confession, there is a greater emphasis placed on the therapeutic benefits. In Orthodoxy, because the penitent tends to repeatedly confess to the same priest – a sort of relationship develops, like that between a patient and his longtime physician. They know your specific conditions, ailments, and disorders. They know what treatments work. It’s a more individualized approach. While (theoretically) Catholicism is dealing with a larger number of prospective penitents, its less like a triage approach and more akin to socialized medicine; with an emphasis on processing numbers or dissuading participation. There is often this stark dichotomy in Roman Catholicism due to the catastrophic rupture which occurred following the drastic deconstruction of the Liturgy; with TLM predominated parishes emphasizing the Sacrament of Penance and more liberal Novis Ordo ones occasionally offering (if at all) general absolution reconciliation services. Catholic priests see the world (and God) through their own ideological lens; in which they envision Jesus – as social justice warrior, gay activist, or “Queer Christ.” Not as a Divine Physician. One of my initial encounters with a Catholic priest, as a returning prodigal Catholic, was truly bizarre. When I attempted to explain to a Jesuit why I wanted to radically change my views and behaviors concerning homosexuality; he assured me that no action on my part was necessary – except for perhaps a renewed search for a lasting monogamous relationship with another guy. In his mind, God made me gay – therefore, gay is good.

In addition to the more public nature of Confession in Russian Orthodoxy, there was also the frequency – before the reception of the Eucharist. Honestly, at first, I thought this practice was completely heavy-handed and unnecessary. In the beginning, I resented this requirement, but I confessed anyway. And, it wasn’t difficult to come-up with a persistent sin: my extreme hatred for the Catholic Church. I had to confess it over and over again. Not because I felt any guilt about it. I didn’t. I rationalized it this way: The Church had brutalized me as a child; therefore, I deserved at least the freedom to openly hate and despise them. Only, this right to indulge my need for revenge – they hurt me/I will hurt them – didn’t afford me the pleasure I thought it would. I was being eaten alive. Intense hatred required a massive amount of energy and concentration. What I despised was enormous, therefore – my hatred had to be just as big; or even bigger. Then, I had a strange thought: I almost wish I’d been abused by some random stranger. Consequently, he would have been jailed or died of old-age. And there could have been some sort of resolution through justice or the passage of time. But the institution of the Catholic Church is ostensibly eternal, like the city of Rome itself. The edifice remained. And the constant reminders of my own abuse and the subsequent indifference by the hierarchy. By the time I turned to Orthodoxy, I began to reach the following conclusion: My hatred was never going to bring down the Catholic Church. I had to walk away. The final scene from the 1959 film “The Nun’s Story” kept replaying through my head – when the character played by Audrey Hepburn finally leaves the convent. I had always been sympathetic with her plight in the film – the attempt by the Catholic Church to control this woman’s mind through manipulation and programming; for example, the pivotal scene in which the Mother Superior tells her to fail an important university exam (on which her future as a nursing-sister depended) in order to prove humility. Brainwashing.

For months, every week, I confessed the same thing: anger and hatred. Yet, in the most fatherly way possible – that never became patronizing – the priest kept guiding me towards a process of healing through forgiveness and prayer. Perhaps, beginning with a prayer for my abusers…for their conversion. That was something I could manage. Albeit begrudgingly, I did it. I did not like it. And it never got easier. Yet, I also kept confessing the same thing every week. This frequency kept my hatred before me – as opposed to confessing once a month. One Sunday, even though I had confessed my anger, afterwards I could not bring myself to receive Communion. I knew that God forgave me, and my amendment was to change, but I couldn’t concentrate on anything except my own victimization. So, I didn’t walk towards the altar when the priest emerged from the Royal Doors holding the precious chalice. This self-exile to the back of the church made we want to do better during the coming week. And I did.

Only, I wasn’t alone when I deliberately stood back and did not present myself for Communion. Right away, probably at the first Orthodox Liturgy I ever attended, I observed the rather large number of people who attended the entire Liturgy, prayed reverently, crossed themselves and bowed at the appropriate occasions, and venerated the icons – except they did not receive Communion; one of the most edifying incidents I ever observed (in any church) was an incredibly understated and deferential young couple; they hadn’t approached the altar for Communion, but they did walk towards the small table placed (afterwards) in the nave where a tray holding pieces of bread (Antidoron) had been placed. They reached out for those crumbs of bread, held them, and consumed them with far more reverence and devotion than so many Catholics in their own Church who treat the consecrated host placed into their hands like a cracker or cookie. This goes part and parcel with a general loss of faith in Catholicism concerning the Eucharist; where 69% do not believe that the bread and wine at mass become the Body and Blood of Christ. Hence, the overall lack of respect towards Communion (see the position of the tabernacle in many churches) amongst the laity.

I probably first saw this start to take place in the early-1970s when we were ordered by the recently defrocked nuns to only receive Communion in the palm of the hand – not on the tongue; as previously had been the tradition. From that point onward, what small speck of mystery that remained in Catholicism (following the stripping of the altars in the post-Vatican II period) quickly disappeared. Consequently, the Catholic Sacrament of Communion became primarily a communal meal that was epitomized in my generation with the linking of hands by children and the priest around the altar – during the “consecration” of the bread and wine.

While a Catholic, I never saw more than one or two people at church who did not receive Communion. Even at weddings and funerals, when there are significant groups of lapsed-Catholics, who do not know when to sit, stand, or kneel, that still inexplicably receive the Eucharist. What these people do (inside or outside the church) is none of my business, yet the humility of those who did not receive in the Orthodox Church are an inadvertent public witness to the importance of the Sacrament and the reality of Christs’ Real Presence.

“The nous is that which is in the image of God. This image has been defiled with sin and it must now be cleansed…we can affirm that man’s cure is in fact purification of the nous, heart, and image, the restoration of the nous to its primordial and original beauty, and something more: his communion with God. When he becomes a temple of the Holy Spirit, he is cured. The Saints are those who are cured.” – Metropolitan of Nafpaktos Hierotheos

The Orthodox have a fuller, richer, and more holistic view of the soul than Roman Catholics. Defined as the “nous,” St. John of Damascus described the unity of the nous and the soul:

“It [the soul] does not have the nous as something distinct from itself, but as its purest part, for, as the eyes is to the body, so is the nous to the soul…”

The nous senses the outside world, and thus can become contaminated by its fallen nature. St Maximus stated: “When the nous associated with evil and sordid thoughts it loses it intimate communion with God.” Thys type of sickness of the soul has been somewhat sentimentalized as a “heartache” in terms of romantic love; but also hits close to the mark with anecdotes such as: “They died of a broken-heart.” This sounds impossible. However, the influence of evil affects not only the spirit, but the body and the mind. In the modern world, probably the most clear-cut example is the effect of pornography on humanity. It skews the perception of love, intimacy, and sexuality; which has resulted in the strange spectacle of sexual dysfunction in young males and their unwillingness to marry. Yet, this sickness has also impacted the wider world with pornography viewing raising the rates of same-sex marriage acceptance among heterosexual men.

This is a complex problem that is primarily rooted in the spiritual vacuum which has ever expanded within Western society. The proliferation of divorce, the removal of parents from the home by the capitalist system, and the cult of acquisition has resulted in the dissolution of age-old bonds of family and community. With feeble replacements such as the odd phenomena of clinical depression and the proliferation of antidepressant use, the desolate landscape of urban homelessness and mental illness, the encroachment of drug addiction into rural Middle-America, the epidemic of increasingly virulent sexually transmitted infection, and the curious rise of homosexuality and the transgender movement.

Over the years, I successively attempted to ease my pain with each of these false balms. Nothing helped. In fact, everything only got worse. For a couple of years, I saw a multitude of specialists: various physicians, psychiatrists, counselors, as well as a few Catholic priests – some with familiarity in spiritual “deliverance” and exorcisms. The attempt to treat this sickness (in all its physical manifestations) were torturous. As I got prescribed one medication – a resulting side-effect would necessitate another. Soon, I was daily swallowing a handful of pills. And I still could not sleep or stop shaking. Sincere Catholic priests prayed over me; I got repeatedly anointed. I would feel better for a while; then, the pain returned.

That which ailed me wasn’t being addressed – my past abuse. And the ensuing anger and hatred. The dirt and filth needed to be literally washed from my body. And that could only happen through Baptism. But that was only the beginning of the process. Because the grime has been ground into the deepest layers of my skin. Frequent Confession was a means to slough off those deposits of misery. Every time I confessed those sins – and the priest placed his vestment over me and then removed it – it was like all that hatred was coming off me. All of us need this scouring. It’s painful. And it requires some trust. In the beginning, I hated it when a priest got substantially close to me – as is the case during Confession. I didn’t like it. But during his public ministry, surrounded by His Apostles and the community of believers (as well as the curious) Christ healed those he touched. Orthodoxy, more than any other form of Christianity, maintains that tradition.

Christ Himself said: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick.” And I have seen many of those who are sick – finding refuge and hope in Orthodoxy. The embodiment of such a wanderer is Fr. Seraphim Rose; a California-native who drifted from marginal Protestantism to Zen Buddhism and sexual experimentation in San Francisco to Orthodoxy. As a celibate Russian Orthodox monk, he frequently wrote about the pains suffered by those who are lost in the world – describing this sorrow as a “pain of heart.” For those such afflicted, the only remedy is conversion. He wrote: “The right approach is found in the heart which tries to humble itself and simply knows that it is suffering, and that there somehow exists a higher truth which can not only help this suffering, but can bring it into a totally different dimension.” For the newly diagnosed, who have been ill and left abandoned for years, frequent treatment is a necessity. And I found such caring physicians in Orthodoxy. And for that – I am eternally grateful.

Good post. I can’t overstate what great benefits I’ve received from (Orthodox Christian) confession. Forgiveness, yes, but permanent healing too. Like you, I’m new to the Russian practice. I was skeptical at first, but it’s helped me to dig deeper. God bless.