“Murder and arson, betrayal and terror.

Mutilate your subjects, if you must.

But with my last breath, I beg you…

…do not mutilate the arts.” ― Gaius Petronius, “Quo Vadis” (1951)

The mass production of inexpensive religious devotional objects is as old as civilization itself. The Ancient Egyptians left behind a vast assortment of various scarabs and little funerary statues called Ushabti. During the early Christian era, ornate and simple votive crosses (made of gold, silver, or bronze) were widely available throughout the Byzantine Empire. Often depending upon the material used, and the prospective wearer, some of these crucifixes are now considered masterful works of art; others are rather crude. But through the Renaissance period, anything larger than small devotional objects were mainly the privy of the Church, clerics, or the increasingly wealthy and influential patronage of the new merchant-class. Yet with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the ability for the common man to own a variety of religious objects became a reality. And contemporaneous with the mechanization of production was the ease of travel across much of Europe via the ever-expanding railroad system. Also, in the 19th century there arose popular pilgrimage centers, exemplified by Lourdes in the West, and a wide network of pilgrimage routes in Russia – as described in the classic anonymously-written book “The Way of the Pilgrim.” At the same time, pilgrimage centers became a locus of commerce; this phenomena particularly troubled St. Bernadette Soubirous who’s own sister operated a souvenir shop in Lourdes.

The grounds for the modern proliferation of commercially produced religious imagery were laid after the Reformation. The art of the so-called Counter-Reformation was characterized by an often grander-than-life scale, brilliant colors, a sense of heightened emotionalism, exaggerated perspective and sometimes accompanied by florid decoration. Much of this art I would compare to the advent of CinemaScope in the 1950s motion picture industry. With the popularity of television, movie theaters rather quickly lost a large sector of their consumer base; as a result of the Reformation – a large portion of Christendom left the Roman Catholic Church. In an attempt to draw back their customers to the movies, Hollywood studios introduced the wide-screen format (interestingly, for the first time, in a religious picture – “The Robe” from 1953); that same year, appeared the first of many films shot in 3-D. The 1950s were also the era of the “Biblical spectacle,” that was well-suited for the large CinemaScope screen; the best of the genre included “The Ten Commandments,” using VistaVision, “Ben Hur,” and “King of Kings,” in Super Technirama. Like Baroque art, these films were big and showy, sometimes gaudy, even pushing the erotic envelop into the realm of bad taste as is the case with some lesser-known examples such as “The Prodigal” and “Sodom and Gomorrah,” but at their best they also sometimes had the ability convey great pathos.

Early on, Counter-Reformation art seemed to go immediately wrong; the most blatant example of the excesses in Mannerist art is the famous “Madonna with the Long Neck” (1534–1535) by Parmigianino. Here, the sensual portrayal of Our Lady is uncomfortably explicit and highly salacious. A century later, Counter-Reformation art reached an apogee with “The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa” by Bernini. This sculptural group is tour-de-force in terms of artistic mastery of the medium – in this case: stone and metal. Bellini created a high-art diorama. The reclining marble body of Saint Teresa seems to float in space; above her is an angel (with his garments wafting around him) holding a gilded arrow – suspended from the ceiling are golden metal spires that become illuminated when sunlight shines through a specially positioned opening in the roof. But the viewer is merely an observer in this play – not a participant. It is beauty for beauty’s sake. Later, the Baroque remained celestially dazzling, but overly busy and distracting. Particularly in Catholic Spain, where the backlash against heresy was the strongest, Baroque art devolved into mere decoration – as evidenced in the “El Transparente” altarpiece at the Cathedral in Toledo; which featured the same utilization of natural light as “The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.”

In the 19th and ealy-20th centuries there was a series of Marian apparitions – especially in France; they included the apparitions in Paris, La Sallete, Lourdes, Knock, Pontmain, Gietrzwałd, Pellevoisin, Fatima, Beauraing, and Banneux. Pilgrimages to such locations far surpassed the mass movement of Christians across Europe, usually towards Santiago de Compostela, during the Middle Ages. Along with the advent of “Catholic tourism” was the emergence of religious “kitsch” initially sold through souvenir shops located near heavily-visited shrines and basilicas. From surviving 19th century examples – the quality ranged from esthetically thoughtful to tacky – like an electrified pot-metal reproduction statue of Our Lady of Lourdes. But despite the cold and distant quality of some manufactured examples, in these French-made representations, a sense of the sacred seems to persist. Such was also the case with the mass production of “holy cards” during the 19th century; which were oftentimes overly sweet and sentimental with candy-box colors, yet remaining immediately endearing.

“He beheld Lourdes, contaminated by Mammon, turned into a spot of abomination and perdition, transformed into a huge bazaar, where everything was sold, masses and souls alike!” ― Émile Zola, “Lourdes” (1894)

In the movie version of Franz Werfel’s “The Song of Bernadette,” there is a crucial scene when the Mayor of Lourdes (who previously spearheaded the efforts to discredit Bernadette) quickly changes his mind regarding the legality of the healing spring at the Grotto when he comprehends the economic boon that will accompany the hordes of pilgrims traveling to his once sleepy and impoverished hamlet. Although the phenomena of religious pilgrimages had already met commerce and vulgarity, notably in Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales,” but French novelist Émile Zola (in his 1894 book about Lourdes) marked the moment when post-industrial pop-culture met religious devotion.

By the mid-20th century, with the relative affordability and ease of international travel, pilgrimage routes crisscrossed the globe. Previously, pilgrimages were almost exclusively dangerous, physically exerting, or reserved for the powerful and wealthy. Even up until the Victorian period, only affluent travelers could afford the so-called “Grande Tour” of the European capitals. During such tours, it became customary for the well-healed traveler to return home with a beautiful and expensive reproduction of a great Italian work of art – such as Michelangelo’s “David.”

According to art historian Clement Greenburg, kitsch is a “simulacra of genuine culture.” A highly vocal proponent of abstraction and a critic of realism, much of the art Greenburg dismissed as kitsch has since been reevaluated by later historians – such as the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In addition, there is also a new appreciation for what was once disdained as the product of capitalist and bourgeoise “pop culture.” This was primarily accomplished through the efforts of maverick writer and academic Camille Paglia who argued that 1960s Pop Art “closed the gap between high and low culture.” In the 1989 music video for the song “Like a Prayer” by the American singer Madonna, Paglia argued that “kitsch and trash are transformed…” But into what? According to Paglia, certain forms of pop culture rise to the same level as museum-quality works of art. This is probably most evident in certain motion pictures. For example, During the studio-era in Hollywood, there are scenes from movies such as “The Searchers,” “Ben-Hur,” and “Lawrence of Arabia” that are undeniably breathtaking. In the realm of popular religious imagery – the big screen met Christian sanctity in the 1950s Bible epic – probably instigated by the monumental Technicolor success of “Quo Vadis” in 1951. In a way, the precursor to these films were the saturated vividly-colored chromolithographs of the late-19th and early-20th centuries – especially those produced in France and Germany.

“You can never compromise with a totalitarian regime because they want everything. Would you have encouraged St. Joseph to negotiate with Herod?” – Cardinal Joseph Zen

During the mid to late-00s, at my brick-and-mortar Catholic religious shops, I noticed a rather sudden shift from the production of sacramentals and statues – away from their historical center in Italy – to the People’s Republic of China. First of all, there was a stark change in the materials used; for instance, statues made in Italy were traditionally carved in wood, marble, or alabaster or sometimes molded in plaster and then hand-painted. Instead, those from a nation autocratically ruled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were made of hallow-resin or fiberglass. These materials were cheap, light-weight, and relatively durable. The problem with the Italian variety was the cost incurred in shipping such heavy objects and the frequency of damage during transport. The quality of these CCP imports ranged from well-manufactured replicas to dollar-store specials. As religious manufacturing in Italy ceased – various importers liquidated their dwindling stock and I bought the last remaining alabaster painted statues made by the “Santini” company. I got them at fire-sale prices so I passed on the savings to my customers and they all quickly sold; even the ordinary man recognized superb craftsmanship.

Later, not realizing they were made by the CCP, I bought a set of statues from an American-based importer that formally almost exclusively dealt in Italian made objects. But almost immediately (once I received them) I thought they looked okay, but oddly lifeless. As many high-tech firms discovered, the CCP is good at imitation, but not innovation. These were uninspired facsimiles. They reminded me of the counterfeit luxury handbags that are sold by street-vendors in Rome. With just a cursory glance, they appear to be genuine; but once you pick it up and perform an even perfunctory inspection – anyone will recognize that it’s a knock-off. Although the religious statues from the CCP were far less expensive than their Italian counterparts, they were also less impressive. They didn’t have the same heft as the ones from Italy. When painted – they seemed cartoonish; almost verging on caricatures. All with the same “Stepford Wife” blank stare. Even though there is a degree of hand-painting that takes place during the production of these figures – they all display a remarkable uniformity. Untethered from the popular piety of the people and the nation, a dull and listless countenance is what defines these statues. However, its not that Chinese artisans are incapable of supreme achievements in religious art – for there are incredibly lively porcelain depictions of the Buddha and magnificently serene examples in gilded bronze that date from before the Cultural-Revolution.

“Art inflames even a frozen, darkened soul to a high spiritual experience. Through art we are sometimes visited — dimly, briefly — by revelations such as cannot be produced by rational thinking.” – Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Shortly thereafter, Communist China began to export large quantities of sacramentals – including Rosaries, scapulars, and oxidized medals of various Saints. In the United States, assisted by a massive mail-order catalogue company, sacramentals could be cheaply bought in bulk and utilized as give-a-way items resulting in a proliferation of plastic Rosaries and acrylic fabric scapulars enclosed in a plastic holder – which completely misses the original intention of a piece of wool worn close to the skin. Items that were once cherished, essentially became disposable. I remember an older man coming into my store and admiring some of the Italian-made statues. He said he had a large antique church-sized one at home. I asked how he acquired it. With an element of sadness, he recounted when a nearby Catholic church “renovated” the sanctuary after the liturgical reforms of the late-1960s. One day, he showed up to see that a large plaster statue of the Virgin Mary had been unceremoniously discarded in an outside dumpster. The statue had occupied a once cherished place of devotion in the church as the centerpiece at one of two side-altars. Over the years, he and his children had prayed before the statue. In those younger days, he was able to quickly retrieve the statue and carry it to his truck. He took it home. And there it still stood. This reminded me of a lady who would regularly bring to me paper sacks filled with unsolicited religious mailings containing CCP-made Rosaries, medals, and holy-cards. She couldn’t bear to throw them in the trash. As a free-service, I went through her mail, removed the sacramentals, and placed them inside a “free-box” in my shop; no one really wanted them.

Perhaps, beginning in the Counter-Reformation, religious art became a tool of propaganda and, as a result – the quality suffered; some of it got sloppy, even solacious. When the political and liturgical interests in the Catholic Church radically shifted in the 1960s, the art that supported the past could be easily dismantled and discarded. The altars were stripped, the liturgy profoundly modified, and the religious life pulled apart and fatally reimagined. What interest remained regarding sacred and liturgical arts in the Catholic Church was negligible and that which was produced looked tasteless and ugly. Roman Catholic art became a simulacrum of a simulacrum. Saccharin-sweet vestments embroidered with the smiling faces of children from various children and stoles emblazoned with the rainbow flag became caricatures of tradition. I remember that at my childhood home-parish, once beautifully painted polychrome statues were replaced by gargantuan monolithic sculptures that resembled the hideous bug-eyed image of Chemosh in the 1960 film-version of “The Story of Ruth.” Because the institutional Catholic Church seemed to be engaged in the purposeful deconstruction of its own artistic tradition – in the ensuing 1980s and 90s, so-called fine artists and some entertainers began to co-opt Catholic religious imagery to the point of sacrilege; the most prominent being Andres Serrano’s “P*ss Christ” from 1987 and Madonna’s music video for her 1989 single “Like a Prayer.” Such extensive profanation of religious art is almost nonexistent in the Orthodox East – except in Roman Catholic Poland where (in recent times) the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa was superimposed upon a “Pride” flag by Polish LGBT activists.

Why did Eastern Orthodox art avoid the plague of sacrilegious imagery which swept through the West in the 20th century?

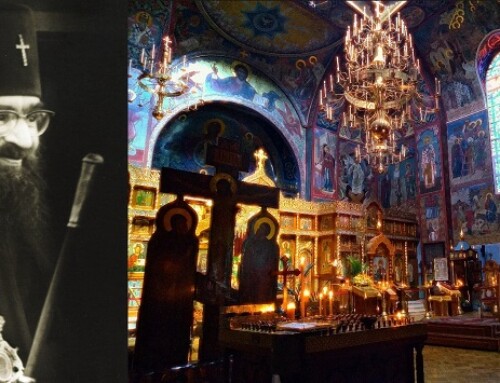

First of all, the Orthodox East never experienced a Reformation; or a Counter-Reformation. Therefore, Orthodox art was somewhat immune to the sometimes-sensationalistic aspects of Mannerism and the Baroque. But the iconoclast controversy of the 8th century did not initiate a secularizing or salacious influence on Byzantine art as occurred in the West following the Reformation. Unlike the more rapturous, albeit extraordinarily beautiful, examples from the Baroque period, according to Leonid Ouspensky: “The icon never strives to stir the emotions of the faithful. Its task is not to provoke in them one or another natural human emotion, but to guide every emotion as well as the reason and all the other facilities of human nature on the way towards transfiguration.” The reverse perspective inherent in most icons reaches out towards the viewer usually through the gaze of Christ or the Theotokos who stares directly outwards from the flat icon panel. In most Western religious paintings, the action is self-contained and the viewer stands just outside the picture’s plane of reality.

Eastern Orthodox art, specifically in Russia, also experienced a prolonged period of almost complete censorship. I would argue that when religious objects are banned and their production prohibited, they become even more priceless to believers. Such was the case in the former Soviet Union – the Soviets forced former iconographers to paint secular themed lacquer miniatures. But countless original icons remained in many homes – while churches were closed or turned into museums, gymnasiums, and Communist meeting halls. Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, icon production practically came to a standstill. The more famous examples, were either hidden or kept on display as sort of cultural relics from the past. While outside the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc states – the tradition continued; especially in France (a focal point for early exiles from Russia) and the United States – with Pimen Sofronov as probably the most well-known artist.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russian Orthodoxy and consequently the Russian religious arts have made a major comeback. This resulted in the mass production of inexpensive reproductions of classic icons and the creation of new icons for recently canonized Saints. When the majority of icons were painted by medieval monks, it was customary for the iconographer to fast and pray extensively while the icon was created. This intense relationship between the artists and the art is the antithesis of the slave-labor sweat-shop factories operated by the CCP. Such asceticism is impossible during the manufacturing process of a large quantity of icons. But there is an authenticity to these reproductions – especially the gold foil embossed icons. Most importantly, they preserve the original power of the icon. So far, only a few Orthodox icons are being reproduced by the CCP– primarily the icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Help which resides in Rome. Strangely enough, in those examples, the rather sorrowful expression from a darker-skinned Theotokos is transformed into a smiling apple-faced distortion of the original. The fundamental meaning of the icon is transformed into something entirely generic. Although iconography is sometimes dismissed, by the disinterested observer, as a repetitive artform marked by uniformity, in reality – there is a remarkable amount of individuality and expansive range of artistic technique; as opposed to the lifeless homogeny in the items from the CCP.

Like much of what is mass produced in our millennial global economy, religious items have become common and disposable. Once upon a time, families would pass-down to each succeeding generation some long cherished statue of the Madonna or a picture of the Sacred Heart. While that tradition is maintained in some families, there is an over-all lack of appreciation and reverence for religious art in the West that is not present in the Orthodox East. Maybe the immense affluence of the West has caused many to take for granted too much – including art and God. This devaluation of religious imagery in the West has resulted in different forms of sacrilege that masquerades as satire; with the worst example being CCP-made nativity sets featuring comic-book characters or various breeds of domesticated cats dressed as the Holy Family, the Three Kings, and shepherds. In “The Gulag Archipelago,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote: “The meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering but in the development of the soul.”

Is it a mere coincidence that while the production of religious objects shifted from Italy to the CCP, the Vatican (with the help of serial pedophile Theodore McCarrick) was negotiating a financially lucrative deal with the CCP? The Vatican not only sold-out the persecuted Christian minority in China, but a part of the West’s artistic heritage. In Russian iconography, the “Kiss of Judas” is not an uncommon image; perhaps, it illustrates how easily – and cheaply – we can all sell our souls.

Joseph where on earth have you been. And don’t stay away so long again please.

This is an interesting topic. I have noticed and been saying, for about 15 years or so, that the statues of particularly, Our Lady, do not have a look I care for. I’ve noticed this at my original source of Catholic inspiration, EWTN, where the image of Our Lady looks almost cross-eyed, to me. It may be something else, but I just do not like the look of the “newer” Madonna, that I see. There are so many lovely representations, there is no excuse for using a revised, frankly unattractive example, but to many people, newer is always better.

When I met my husband many years ago, his mother inherited a statue of St. Anthony that no doubt came with his grandmother or great-grandmother, from Italy. I saw it sitting on a dresser at the end of the hall. How it survived three boisterous boys I will never know, but it did. The eyes, the expression, there was something about it. No modern commercially made statue would be anything like it. When his mom and dad were gone, this was the item we hoped for, and nobody else wanted it, so it is here with us now, and much loved. But will the next generation love it as we have. I hope so. Glad to see you back, Joseph.

Hi Joseph, believe it or not, A LOT of Orthodox items are now being produced in China. Often, they are lower-quality knock-offs of items from Sofrino (the “production capital” of ecclesiastical and devotional items in Russia). My sister was shopping at a discount store in the Philadelphia area, and she came across a bunch of Russian-style icon magnets and crosses–all made in China. Another time, she found keychains of the Mother of God with a prayer in Romanian on the reverse; I think these were from China, too. Given the large markets of Orthodox Christians in Russia, Romania, etc. it isn’t surprising that Chinese companies are seeking new markets. Alternatively, Russian, Romanian, etc. businessmen are probably outsourcing production of items to China, in order to cut production costs.