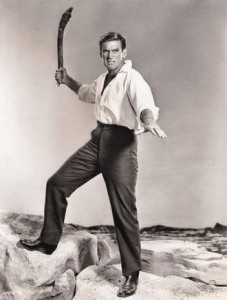

Ever since I was a little boy, one of my favorite films has been “The Time Machine” (1960.) The movie was really the last great adventure picture before the advent of the over-sexed spy films, introduced by “Dr. No” in 1962, and the later introspective banal male characters of the later 60s such as those in “The Graduate” and “Midnight Cowboy.” The lead was played by Australian actor Rod Taylor, who was able to combine a very sophisticated and intellectual persona with that of the rough-and-tumble virile man. In later decades, the two identities would be forever separated in entertainment by the development of the “action-hero” star who was big and brawny, but otherwise limited. A sort of impasse was reached by the meteoric career of Tom Cruise, who, aided by a series of special CGI effects, bolstered his short stature and annoying personality (i.e. the infamous couch-jumping incident during an interview with Oprah Winfrey) into a sort of fake leading man. But, sadly, the days of Cary Grant, Errol Flynn, and Charlton Heston, who were all comfortable and believable as men of cerebral command as well as physical prowess, see Heston as Michelangelo in the beautiful “The Agony and the Ecstasy,” are long gone.

The story begins in the year 1900, as a group of friends reunite to talk with their colleague George (Rod Taylor) who has just returned from an incredible journey into the future. Though they are skeptical, he tells them how he built a working time machine and traveled to the year 802,701. He explains that he discovered a world were humanity has been split into two species: the blonde, weak, and gender neutral Eloi and the bestial, but more intelligent, Morlocks. While the Eloi live in decadent indifference on the surface, the Morlocks run machines in an underground chamber of horrors; were they ritualistically kill and consume the surface dwellers. When George arrives on the scene, his presence is little noticed by the Eloi even though he is ridiculously obvious: for, unlike the ephebic weaklings, he is tall, strong and ruggedly manly. The outward differences are most evident in their clothing and persona: while the Eloi lounge about in pastel silks, George is endlessly inquisitive in his woolen tweeds. Also, with their generic short bobbed hair, the Eloi all look eerily similar. Yet, one of them somewhat stands out, a rather beautiful and curvaceous young woman who is saved from drowning by George. This begins a rather sweet and innocent relationship between her and George, for, she feels instinctively protected by the sheer physical presence of him – unlike the company of the frail and spineless males that have always surrounded her. Although the two genders are barely distinguishable amongst the Eloi, eventually, the male Eloi begin to reassert their inherent masculinity after repeatedly observing the self-sacrificial example of George.

What I continue to find most interesting about the film is the dramatic dichotomy between the masculine and self-confident George, who hates his own time for its reliance upon callous violence, and the male Eloi – the results of hyper-emasculation and a slavish dependence upon sensory pleasures. A sort of lethargy pervades the Eloi. This is not unlike the “coach-potato” syndrome of suburban males or the deterioration experienced by internet porn-addicts. There is also a strong female aura of softness, languor, and self-containment in the Eloi. The counterbalance of macho bravado is completely missing. Therefore, its more than symbolic that the book and film were both published and set during the turn of the century when the once solid foundations of patriarchy and the family in the Western tradition were being supplanted by the social apparatus of the Industrial Revolution: foretelling the rise of the two-parent working household, the withdrawal of male familial involvement, and the question of adolescence. George represents the last of the “Renaissance man” before the institution of over-specialization. Today, we have categorized males into the jock or nerd. The contemporary intellect is epitomized by the whiny Mark Zuckerberg; replacing Steve Jobs – whose cult status grew more as he became thinner and wispier over the course of his cancer illness. It reminds me of the famous “Star Trek” episode in which aliens kidnap Spock’s brain. What “The Time Machine” ultimately advocates is a return to the “whole” male: one who is active, but also passionately thoughtful and open to the transcendent. In essence, a man exactly like Our Lord Jesus Christ: who could valiantly overturn the tables of the money-changers, but also heal the sick with a gentle touch of His hand. Without this type of man, the human race, especially males, degenerate into confusion, depravity, and lifelessness.

This is a very good analysis, thanks a lot. Keep up the good work.

I like your analysis here, Joseph.

God bless.