“…icons, just as well as the Scriptures, are expressions of the inexpressible.” – Vladimir Lossky

I grew up around icons. My father was an immigrant from Sicily. What little he brought with him to the United States – included a few small reproductions of Byzantine-style icons. When I was a child, they fascinated and frightened me. Especially the icons of Our Lady, the Theotokos. When I walked by them, I avoided their gaze. Because, they seemed to stare at me. I thought that their eyes followed my every movement. If I got near them, I sometimes didn’t look up. I thought to myself: “She looks sad – even a little bit angry.”

Yet, in the rooms of my older brother and sister – there were different sorts of icons. In the 1970s, it was the era of the pin-up poster made particularly famous by the red swimsuit photo of Farrah Fawcett. Among my brother’s collection were a variety of Playboy “bunnies” and TV actresses; in my sister’s room were a number of teen heart-throbs; in my own, hung images of Christopher Reeve as Superman and the cast of “Star Wars.” I gazed at them for long periods of time. I studied each one individually. At night, I looked up at the stern visage of Superman with his arms crossed in front of his chest. He made me feel safe – protected.

At school, Jesus was just another pop-star; except he failed in comparison to every comic book superhero. The image of Christ presented to me during my years in parochial school, the one that had the greatest impact on me, was Jesus as portrayed in the film “Godspell;” that of a weak and simpering clown in a big “S” emblazoned on his t-shirt.

Except for my father’s little “prayer corner,” that featured, along with some icons, a statue, and a few holy cards, religious symbols were somewhat absent from my childhood home. Within this vacuum, secular icons easily replaced the sacred.

As a somewhat lonely and isolated boy, I often spent hours endlessly drawing with paper and lead pencil. A cherished birthday gift was a complete collection of 64 crayons – in the box with a built-in sharper. When I got a little older, I received large sets of watercolor markers and colored pencils.

I was never an academically gifted student in grammar or high-school, but I wanted to go to college – primarily because it represented a way to escape what I regarded as the restrictive confines of my relatively small and provincial hometown. Beforehand, I spent a couple of semesters at a local community college. I took a bunch of Art courses and started painting large reproductions of famous Byzantine icons utilizing neon hues of yellow, pink, and blue. At the time, I didn’t know why I chose such subject matter; perhaps my second-rate Pop art treatment of these holy images was my way of debasing them. But after completing my synchronous survey course in Art History, I knew that my limited portfolio was distinctively derivative; I wasn’t good enough for art school. So, instead of applying to various colleges – I sent my application into only one: UC Berkeley. I was accepted – with my major in Art History. Although the campus was located not very far from where I was born and raised, psychologically it felt as if it were on another planet.

During my first couple of semesters, I was incredibly disorganized. I didn’t know what I wanted to study. I chose random courses in French Impressionism, Mayan Art, and Romanesque architecture. But for some reason, I became fascinated by the early-Medieval period; when a professor showed a series of slides taken at Ravenna, I sat mesmerized at the back of the classroom. The mosaics were rich and luxurious – they were magnificent. Elsewhere, for months, I had heard endless lectures that stripped beauty away from great works of art. Due to an overwhelmingly Marxist interpretation, a number of my professors reduced art to a political commodity. As a result, I searched for beauty in the world around me and thought I could only find it still alive in the realms of Hollywood and the gay male subculture.

Walking down Castro Street (from the BART station) for the first time, the front windows of the various bookstores and porn shops, as well as the telephone poles, were often covered with images of the handsome male visage or the nude torso of a muscular man; combined with an atmosphere of sexual opportunity, the air filled with the sounds of electronic dance music emerging from a nearby disco, and the mindset of the observer – who is there to worship at the altar of masculinity, these images took on a certain power or authority that immediately commanded attention and provoked respect. Such pictures could also be described as “iconic;” in the same way that Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange’s famous photo of a “Migrant Mother” from 1936, distilled into a single frame the aspirations and sorrows of an entire generation.

Photography has that uncanny ability to capture and preserve the transitory, but also the transcendent. For this reason, gay men have been particularly drawn to photographers like George Hurrell, Francesco Scavullo, and Herb Ritts; their glamor shots of Hollywood legends, rock stars, and supermodels often have a luminous quality about them; the famous shot of screen-goddess Jean Harlow by Hurrell remains a persistent highpoint in the history of pop culture.

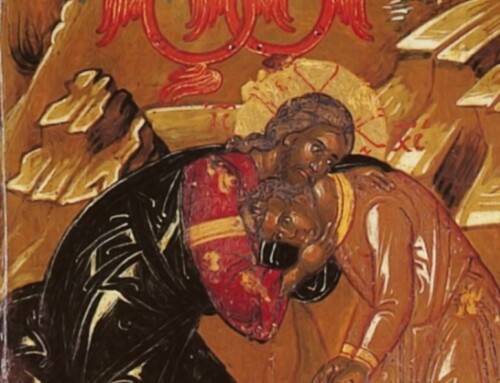

But Orthodox iconography, before the invention of the camera, had that capacity as well, and in its purest form. For instance, in the Korsunskaya icons of the Mother of God, a tender moment between the Theotokos and the Infant Jesus is preserved forever in pigments. From my childhood, I never forgot Our Lady of Perpetual Help – that hauntingly portrayed the moment the Christ-Child, having seen two angels carrying the instruments of His future Passion, leaps into the arms of His protective Mother.

“…all that is depicted in the icon reflects not the disorder of our sinful world, but Divine order.” – Leonid Ousepensky

The Legion of Honor, which housed the European collections for the fine arts museums of San Francisco, held a large exhibition of Byzantine icons. Although the museum curators tried to recreate an atmosphere of mystery with subdued lighting surrounding the icons, in most cases, when works of sacred art are removed from their liturgical setting, they tend to be solely viewed as a work of art, or even worse – as decorative objects. But the force of these images, in particular, an oversized icon of Christ Pantocrator, transcended their present surroundings. In front of it, I stood there. His eyes locked on me and seemed to drill through my every artifice.

A friend who attended the exhibition with me, mentioned a Russian Orthodox church located not far from the museum; I must have lackadaisically driven by it a thousand times, but with its golden onion domes – I thought it was a mosque. Afterwards, we stopped there. I was awe-struck. Illuminated by numerous beeswax candles, the glittering icons shimmering in the shadows seemed to draw me ever closer to them. But I was afraid.

Subsequently, it became routine for me to stop at this church during my frequent trips to the museum. Usually, I would simply walk around and look at the icons – oftentimes keeping my distance. I didn’t believe in their supposed magical powers; and except for those icons of Jesus Christ and Our Lady, I didn’t even know who the various saints and holy men and women were. But I kept going back. On one occasion, I stumbled into a Russian Orthodox liturgy. From the moment I walked through the large front doors, which almost directly opened out onto a busy sidewalk and noisy street, I felt out of place. Emanating from inside, I could distinctly hear a booming sound dominated by male baritone voices. I immediately became uncomfortable, and left.

Throughout my early college years, I regularly attended local art and antique auctions. I rarely bought anything, but they were a free day of entertainment and I thought – education. During a period of my keenest interest, right after the fall of the Iron-Curtain, several auction houses were inundated with Russian icons from the former Soviet Union; in general, they could be acquired rather cheaply. This situation was somewhat similar to the circumstances surrounding the fire-sale prices for precious Russian and Romanov treasures (sold by improvised expatriates) following the Bolshevik Revolution, that were subsequently bought by other European royals, aristocrats, and collectors.

At an inconspicuous auction, I bought a small panel icon of the Theotokos for a relative pittance. She expressed the same sorrowful and somewhat judgmental countenance of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. I didn’t understand why I bought it. But for many years, I dragged it around with me – even as my life descended deeper and deeper into darkness and confusion. However, one day, I placed it in a cardboard box, with some of my other belongings, and left it at my parent’s house. In hindsight, I think I didn’t want it looking at me anymore. I wanted to finally destroy myself in peace.

Only, God wouldn’t leave me alone. After a failed attempt to terminate my life, I ended-up back at my parent’s house; near the front entrance, after almost 30 years, the icon of Our Lady Perpetual Help remained. I still avoided it.

Then, for some reason, I dug through a stack of boxes in a closet. I found mine. I’d left it there years before. I looked at the face of the Virgin – she looked the same. She hadn’t changed, but I had. I took the icon and hung it on the wall – near the door. Every time, I left this room I had to pass by it. Each time, I forced myself to look.

“Sin leaves it’s mark not only on the soul, but also on the exterior of a person, on his outward appearance and behavior.” – St. Nikon of Optina

After a decade of being submerged in a disordered life – there was nothing about me that was ordered or healthy. I had slowly destroyed my physical health. Using parts of the body for purposes they were never intended had caused a fierce reaction in my physiology. My body was in revolt – for years, I endured and semi-recovered from a series of ever-worsening infections. On a societal level, this individual battle with the body played out on a wider scale inside the gay male community through the ravages of AIDS. Healing the body would test my patience and my willingness to endure suffering. But the reparation of the soul required that I undergo a level of pain I never thought I could withstand.

In the icon – there is a reverse perspective. Unlike in many Renaissance works of art, the vanishing point does not terminate at some unknown spot on the horizon, but inside of the viewer. Through the icon, I encountered a true image of Our Lord Jesus Christ – He challenged me. I returned to the image of the Pantocrator. Although an unknowing observer may remark that icons appear uninspired and constrained by artistic convention and traditional rubrics, yet various icons of the same subject never look exactly alike. Somehow, I found one that spoke to me. Overall, He wasn’t the pathetic and scrawny symbol of a disinterested and relativistic all-accepting deity; He wasn’t the Jesus from my childhood. He was authoritative and commanding, but also strangely compassionate and openhearted; as if Christ in the icon were looking down on you from the Cross. Similar to His Holy Mother, this icon of Christ was both confrontational and welcoming.

When I was a boy, like every good parent, like every good father, and every good mother, Our Lady saw me for who I was – not for the person I thought I was, or for what I had become.

Icons remain singularly mysterious to me, but they consistently reveal the inner torments of the viewer.

“Behold, the eyes of the Lord are on those who fear Him, on those who hope in His mercy.”

Slowly, I grew to love Our Lord; but I first had to fear him. For the majority of my life, I avoided His gaze. I ran away from Him – to places where I thought He would never follow. But He did. I placed in front of my eyes – an assortment of new icons that I could adore. Only, they were lifeless and cold; they promised salvation, but handed over nothing. True sanctity requires suffering and frequently it makes us uncomfortable – for we are faced with the reality of our sins and how they have transformed us into something we are not; oftentimes into something ugly.

Although I had graduated from college, I didn’t visit the museum as often, and I moved out of San Francisco, but I still made the effort to visit the Russian Orthodox church whenever I was in the neighborhood. However, one day I planned to attend a Sunday liturgy. I was trepidations, but I took off my hat, walked through the vestibule and into the church. I stood way in the back, and I didn’t participate in any way – for the most part, I didn’t really understand what was going on. Yet, from my vantage point, I could still see the face of large panel icon of Our Lady. I thought, for a few seconds, she smiled at me. I wasn’t afraid any more.

Happy Easter Joseph.