“Behold, I go forward, but he is not there, and backward, but I do not perceive him; on the left hand when he is working, I do not behold him; he turns to the right hand, but I do not see him.” (Job 23: 8-9)

“Look to the right and see: there is none who takes notice of me; no refuge remains to me; no one cares for my soul.” (Pslams 142: 4)

“On my bed by night I sought him whom my soul loves; I sought him, but found him not.

I will rise now and go about the city, in the streets and in the squares; I will seek him whom my soul loves. I sought him, but found him not.” (Song of Solomon 1: 1-2)

A note about the above photograph: During an outreach to a gay “Pride” event in San Francisco, I was rendered almost speechless after happening upon a group of gay men representing a circuit party organization called “Cumunion.” I recognized this immediately as a play on the term “Communion.” After talking with them, and after seeing some of the disturbing visual material they had on display, it was clear that this was a strange and rather hopeless recreation of Christian ritual and sacramental theology reimagined as a gay orgy with a particular emphasis on a sort of spiritual bonding through bodily fluids – a sick perversion of the Eucharist. But I felt no animosity or even disgust for these men; because I understood this for what it was – a desperate need to touch the transcendent in a fallen world.

When I walked into the “gay” Castro District of San Francisco, I was eighteen years old, I was scared, and I was lonely. It was the height of the AIDS crisis; at the time, an HIV diagnosis meant an almost certain early death. But, I didn’t care, because something was drawing me there.

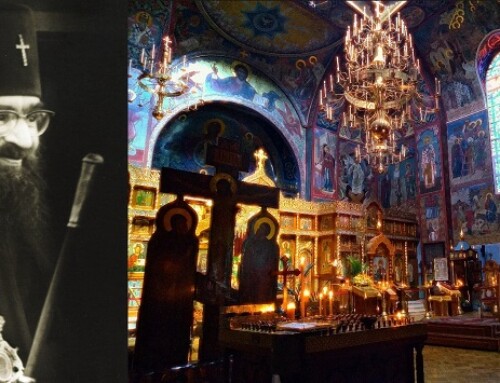

When I was a child, I had a natural curiosity about God. Looking at the ancient icons of Christ and Our Lady, that my father brought with him to America when he emigrated from Sicily, God looked otherworldly and sacred. I also remembered a small Italian marble reproduction of Michelangelo’s Pieta. And, then there was probably the greatest spiritual idol of my adolescence: Charlton Heston’s massively heroic performance in “Ben-Hur.” He was the manly proto-Christian standing at the foot of the Crucifixion: transcended by God, but somehow made stronger through his encounter with the Divine. Years later, while studying Art in college, I was almost offended by the Northern Renaissance paintings of an overwrought or swooning Virgin Mary collapsing at Calvary; instead, I was attracted to the usually stalwart St. John or, even more so, the pillar-like continence of Longinus on Byzantine icons.

In the seemingly incongruous translucence and rigidity of the icons, in the solidness of the Pieta and even in the chiseled proportions of Charlton Heston’s face, in my mind, God materialized as both dependable and timeless. It’s no accident, that one of the legendary landmarks on the constantly cruisy gay enclave of Polk Street in San Francisco was the beefily named porn-shop “Ben-Hur.” Its lighted sign beckoned lost boys from throughout the country: the abandoned and the abused, the frightened and the forgotten, towards a symbol of the eternal masculine.

In Catholic school, God was instantaneously transposed from the mystical to the mundane. In a failed attempt to make Jesus appear accessible, He suddenly became irrelevant; just another enlightened teacher in a long line of ultimately failed and martyred humanitarians. Jesus also looked feeble and slightly effeminate; he was a strange amalgamation of hippie Jesus Christ Superstar, perfectly realized in the sentimental illustrations of artists Frances and Richard Hook, which coincidentally covered the walls of our classroom; add to this, the clown-faced Christ in the film-version of “Godspell,” and the 1970s “Jesus Freak” movement. In the 1980s, when I became a teenager, Jesus felt oddly dated – as if He were still singing bad folk-rock.

Sadly, this disconnect continues in many Catholic parishes, especially in the most progressive, through the enduring presence of guitar-masses, daisy-chain hand holding, and the removal of the Tabernacle to a side-altar or even another room. When I returned to Catholicism in 1999, in my own local parish, with no corpus of Jesus on a Crucifix – the Body of Christ was conspicuously missing. Most of the liturgical duties, lectors, extraordinary ministers and even altar servers, had been taken over by women. And, as a consequence, I saw how the Mass could quickly turn into an emotional female-driven form of group therapy with the priest merely serving as the facilitator. In addition, the inexplicable permanence of the insipid music from Dan Schutte and the St. Louis Jesuits within the liturgy revealed a continued sappiness that is particularly off-putting to men. I will never forget, within months of leaving the “gay” world, I somehow found myself inside the thick-walls of a Romanesque monastery in France – hearing the manly voices of the Benedictine monks, rich with tenors and deep baritones, I felt completely transported from my present dreadful circumstances. This was the antitheses of the earth-bound and highly limited vision of God that I experienced as a child.

At the end of the day, as the monastery become ever colder and darker, there was an inexplicable blaze of warmth emanating from a circular grouping of monks kneeling about a small stone figure of the Virgin and the Christ-Child. As I approached, it was like stepping into a Bethlehem scene of the shepherds huddled around the Christmas cave. While I still heard the faint echoes of the Gregorian chants in my head – I could finally see that God, and the men who loved Him, were big and bold like Christ, but also gentle and humble before the Incarnation of the Divine in this baby boy.

As a “gay” man, I constantly worshiped at the altar of masculinity; although in the homosexual schema of pure manliness, any semblance of compassion was banished as a mark of softness. For this reason, sex often became gritty and curiously faceless – sometimes singularly focused on the most primitive of totems, the phallus, whereby an anonymous male would stick his erect member through a hole in a wall and the slobbering man on the other side would bow down to adore it. That was my initiation into “gay” sex.

The fleshiness of the substantial that I unconsciously sought, even in Jesus Christ, nearly disappeared in the Catholic Church of the 1970s. For myself, a pivotal moment took place when, for the first time, the consecrated Body of Christ was dropped into my grubby little hands; it was as if the sacred had fallen to earth. Pope Benedict XVI himself once commented: “I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy…” Benedict continued, that often inherent within the environment of liturgical abuse is the individual’s difficulty to grasp what is “the encounter with the mystery.”

Because, I believe, that Man has an instinctive desire for the transcendent, when a religion no longer offers an “encounter with the mystery” of God, some will seek it elsewhere while others abandon the idea altogether. For instance, as the liturgy, and Catholicism in general, began to lose its sense of the sacred, there are arose a series of feeble replacements: hallucinogenic drugs, the rise of interest in Eastern spirituality, the New Age, hardcore pornography and virtual reality. In the late-1980s, when I was getting deeper into the occult, I watched as my friends, other boys who grew-up in the downgraded Catholic era of the Mass as communal meal, became lost in the incense and gongs of Tibetan Buddhism. While a larger group, outwardly chucked any semblance of religiosity and became purely secular – achieving a sort of happiness in career advancement, retail acquisition, and recreational sex.

But, inside “gay” culture, even evidenced within those who had knowingly abandoned the deritualized Catholicism of their youth, there emerged a concerted drive towards a hyper-kinetic form of the sacred…in the male body and in sex. Here, I think there was a direct trajectory between the Catholic liturgy which was moving away from the solemn inviolability of the Tridentine Mass, with its inherent symbolism of the Body and Blood of Christ to a more folk-concert conception of a shared communal celebration with an endless line of communion cups, often handed out by women – and overseen by a grinning priest who was now constantly faced the people – and the rise of “gay” culture, where the male body was on full central display. For many of the young men who literally created the burgeoning gay culture of the 1970s were former Catholics. For example, Catholic-educated “gay” historian Michael Bronksi once nostalgically remembered the relatively new gay sex scene in San Francisco’s SOMA [South of Market] during the late-1970s; at one such sex club, The Black and Blue, he described the inspiring aura which took over at closing time and the near reverence the men payed to a suspended Harley Davidson, that hung over the club’s bar, like a “magically elusive” symbol of masculinity:

“Once a night the music…would stop, lights in the bar would be dimmed to near complete darkness, and perfectly on cue, stage lighting would illuminate the bike from the corners of the hammered-tin ceiling. It was a stunning sight, and when it happened a magnificent hush fell over the bar. Within moments of the silence falling, the music would begin: it was always the Gloria from Bach’s Mass in B Minor. For those seven or eight minutes there would be nothing but Bach’s transcendent music and the gleaming chrome of the illuminated motor-cycle. The Black and Blue had become – as it always, in some dimension, was – a church. Every night this moment felt, to me, startling and sacred, even holy.”

Interestingly, Camille Paglia, the Catholic-raised lesbian Humanities professor turned atheist, found the same surprising specter of religiosity in “gay” hardcore pornography; of a porn film depicting the practice of fisting, Paglia wrote: “I was deeply impressed by an early pornographic film I saw of these activities. It had the solemnity and gloom of a pagan ritual, like the tableaux of Pompeii’s Villa of the Mysteries. Sex as crucifixion and torture.”

As the colorful polychrome statues of the martyred Saints, often gruesomely explicit in the depictions of their bodily tortures, were unceremoniously removed from the church niches; and, as the theology of the Incarnation (from the Latin word meaning flesh) was deemphasized in favor of a relaxed lay participation in the Mass – as Pope Benedict remarked, a “disintegration” took place. This occurred not only in a growing disregard for a reverence of the sacred, but in a near collapse of the mystical realities of religion. As a consequence, in the minds of many: Christ, in becoming more human and less God, drifted into a corporal form of decay – He simply became a man who lived and died, but who was no longer present. The certainty of Christ, as a Divine substance of both Spirit and the Flesh, was unimaginable. In this vacuum, a new religion was created, often picking up the shattered pieces of the old and then reworking them into an ultimately demonic phantasmagoria of blood and sex.

Like Bronski, I too found the world of San Francisco all-male sex often frighteningly disturbing, but hypnotically attractive. In the often dark and dank caverns of the Castro neighborhood and the Folsom Street sex clubs, there existed an almost consecrated monasticism solely devoted to masculinity. Here, alienated and often peevishly frightened young men, who never knew either the love from their father or the acceptance of male peers, were instituted into a brotherhood of shared pain. Amongst themselves, they tried to pray the sorrow away by worshiping each other. Only, one of the problems, unlike the monks in France, is that single-minded focus on the masculine has wrought not peace, but incessant restlessness. St. Louis Marie de Montfort wonderfully recognized that True Salvation was conceived in a woman; he wrote: “No one but Mary ever found favor with God for herself and the whole human race…The patriarchs, prophets and the saints of the Old Testament yearned and prayed for the incarnation of the Eternal Wisdom, but none of them was able to merit it…Only Mary.”

In their panic to avoid the necessity of a biologic complimentary, homosexuals have rushed to somehow sacramentalize their unions in the frantic unwarranted urgency over “gay marriage.” In addition, gay couples, especially males, endlessly manipulate the body through advances in scientific procedures to unnaturally produce children. Despite the hype, the vast majority of “gay” men are choosing to remains single: the share of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults who reported being married to a same-sex partner rose from 7.9% before the Supreme Court ruling to 9.5% and has since leveled off at 9.6%. Men, without women, do not settle. Instead, what you have in male homosexuality is a never-ending cycle of initiation ceremonies in which no one is ever initiated.

I will never forget my first time at a “gay” sex club. With other men, most coldly familiar with the routine, and another semi-petrified teenager, I waited to pay my nominal entrance fee. While I stood outside the door, I could hear the incredibly loud snaps from a whip. A few minutes later, I was confusedly walking about the club’s lounge area. The decorations were a strange mix of Art-Deco chrome overload and the interior of the gilded Egyptian barge from Elizabeth Taylor’s “Cleopatra.” In the background was the constant thump of electronic dance music. The atmosphere was solemn, even reverential. Later, I would initially witness this same devotion when I attended the San Francisco “Pride” parades which slowly glided down Market Street like a religious procession. At the Folsom Street Fair, with the various live sex performances, this reverence took on a mysterious solemnity when men from every-walk-of-life would stop dead in their tracks and silently watch, almost in a state of euphoric bliss, as fellow devotees would become naked false high-priests acting out strange sexual tableaus.

At this particular club, almost like Dante, you advanced through a series of rooms – the first being the locker rooms where every participant was required to completely disrobe. Next, there was a bath and stream-area; here you went through a weird simulacrum of Baptism. What followed were increasingly darker and smaller rooms: a mirrored space with weights and exercise equipment, a collection of small glass walled cubicles with wall-mounted television screens that endlessly looped gay porn, and a torture chamber equipped with cross-beams that looked positively medieval. Finally, as if you are a pilgrim walking towards the Holy of Holies, you reach a nearly empty almost pitch black rubber-lined room. All I could make-out were the passing shadows. It was the “gay” heart-of-darkness. Where I wanted to reach out and touch and experience the solidity of the male body, in the end – here, it proved to be as elusive as ever.

It’s no coincidence that “gay” male sexuality often takes on the superficial imagery of traditional Catholic and Orthodox religious practices. For in a world where the mystical has been replaced by the mundane, where the once central role of men in religion was taken over by a committee, and where the centrality of Christ’s eternal Body has been replaced by the transitory glee of hand-holding, some men, who have been particularly traumatized within a culture of missing or disconnected fathers, will retreat into a radically purified form of masculine spirituality. Yet, as is the case within male homosexuality as a whole, the fearful absence of women creates a testosterone-fueled miasma of sexual libido gone out of control. I initially realized this when I took part in semi-historic gangbang of a single blind-folded man who willfully submitted to a long line of successively ejaculating males – the variety of men in the waiting crowd was astounding: from the physically admirable to the visibly diseased. Hence, the depths of perversity, that I found nowhere else in society, seemed almost limitless among “gay” men; because, even if well paid, no woman, unless psychologically disturbed, would submit to such a thing. However, like everything I encountered in homosexuality, that lineup was revolting and eerily sacred as if we were participating in a collective sacrifice, all taking our turns, on some blood-drenched altar. I was semi-revolted, except within the year I would take part in a similar scene – this time, with a dog collar around my neck.

Many years afterwards, that experience remained as a predominant symbol in my mind, until I finally witnessed the incandescent beauty of the monks praying, late into the night, around the statue of Mary and the Child-Jesus in their darkened stone chapel. This was true masculinity, tempered by their love for the Holy Virgin. In the “gay” world, there is no such moderating influence – so, in a sense, one had to be invented.

When the singer Madonna seemingly out-of-nowhere became instantly famous, her exuberance and joy for life transformed the tackiest of sexual innuendos into the realm of the avant-garde; this was probably best realized in her early music video for the song “Borderline.” But, inside of a few years, she became darker and probably made her most famous statements with “Like a Prayer” and “Justify My Love.” Here, Madonna, a constant cultural scavenger who appropriated and sold “gay” tropes like no one else since The Village People, combined Catholicism with sexual blood rituals in “Like a Prayer” and then created a whole series of sinister sex rooms in her mini-movie for “Justify My Love.” At the time, too controversial even for MTV, Madonna drifts from one room to another where different participants engage in a variety of sex acts. It’s a sinister play on the “many mansions” imagery of the Bible. But, like the deepest recesses of the “gay” sex clubs, these rooms only contain a shallow promise of contentment for those lost souls who enter.

Beginning in the 1990s, with her troupes of fluttering seemingly neutered male dancers, Madonna became Cybele – demanding emasculation from her more serious devotees. Near the millennium, I met a young new arrival to the Castro – a Midwesterner who, as a child, repeatedly shocked his disconnected and overworked father by dressing-up as Madonna and lip-syncing to her music whenever he crashed at night in front of the TV. Recently, Madonna has become angry and sullen – morphing into Faye Dunaway as Joan Crawford: punishing those she pretends to love; even causing her son to flee his mother’s presence. Like the camp-film, “Mommie Dearest,” which the gay community continues to cherish, Madonna has somehow sanctified abuse as a bizarre ritual of compassion. Again and again, this scenario plays out in homosexuality, where the neglect and fevered need for attention in childhood becomes a sort of self-flagellation; a last ditch desperate plea for recognition.

Madonna’s songs still are on the playlists of gay discos, and she continues to hit #1 on the dance charts, but she has been overpassed by a group of younger women who were self-admittedly influenced by her. Like their predecessor, many of their lyrics play upon the theme of pleasure in corruption, namely: Katy Perry in “ET,” Rihanna in “S&M,” and Lady Gaga in “Bad Romance.” We haven’t seen this amount of mass hysteria since the post-Black Plague era of European history when roving bands of unnerved flagellants beat themselves, and each other, into a bloodied frenzy. They were reacting against a deeply religious culture where God appeared to have failed. Today, with the ongoing horrors of AIDS, specifically gay men, have taken self-punishment to the extreme, because they perceive not a God that has failed, but a God that is dead.

In their hearts, homosexual men, especially after they spend a few years amongst their fellow unsatisfied travelers in the bars and dance-clubs, slowly begin to subconsciously realize that the “gay” experiment failed. At that point, a few of them permanently attempt to check-out from the scene and imagine that none of it ever happened. As a result, they regress back to their childhood fantasies of a perfect 1950s TV-sitcom family, and recreate what they never had.

At the other end, a still sizable group of men, instead of signaling defeat, rage on and intensify their quest for eternal manliness. These are the ones I encountered in the bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs; these are also the men who continue to endlessly search for the perfect realization of manhood by constantly scrolling through thousands of headless torso and crotch shots on the gay social networking app Grindr. This focus on a single part of the male body harkens back to the fetishistic occult phallus charms of ancient Rome.

In a world where the mysterious and transcendent has been eliminated, even from the churches, starving men search for some connection to God. In the modern “gay” headspace, this union with the Divine can only take place by joining with the masculine through the seemingly perfected male body. Here, there is an overt perversion of the Incarnation, wherein the corruptible body takes on a magical property that, as a substance, can be transferred to others. Hence, when I witnessed the reemergence of bareback sex in the late-1990s, which had continued unabated to this day, and the fascination of “gay” men with receiving the body fluids of their partner; according to the CDC, 64% of gay men reported condomless anal sex at least once in the previous year, with 37% reporting anal sex without a condom with a casual partner; in the UK, The Gay Men’s Health Charity reported that 39% of gay men have unprotected anal sex a “majority of the time.” Despite the risks, not only due to HIV, but also including a sharp rise in antibiotic resistant gonorrhea and a marked return of syphilis, gay men are prepared to risk their lives for what they comprehend as a life-saving encounter with something which they believe will prove transformative.

Only the gods of gay demand much, but return very little. Unlike the redemptive suffering of the Saints, with homosexuality: there is no resolution. This sad drama of punishment without purpose is evident in the continued gay male fascination with specific films depicting unjust oppression and enslavement; repeatedly at the Castro Theater in San Francisco, I often watched transfixed, as they replayed certain Cinemascope films that curiously appealed to their gay male clientele: “Ben-Hur,” “Spartacus,” and even “The Robe.” Of keen interest were the depictions of sadism and cruelty. And, like much that is hollowed in gay culture, these movies aimed for the loftiest of human endeavors – to touch God; and for the most part, they were successful. As they have a broad scope and magnificent emotional power that can be compared to the illusionistic ceiling paintings of the Baroque period. But, in the fallen gay context, their impact is perverted and the power of restoration through anguish and trial becomes perverted into a caricatured form of sexual debauchery.

Oddly enough, I still believe that the makings of sanctity still exist within the often twisted conceptions of “gay” men. For, as a once tormented boy, who later submitted to being a tortured gay man, within those who suffer with same-sex attraction, resides an intense desire to understand the truth and meaning in our often agonized early years. Because of the isolation and loneliness that is inherent in the confused battle we regularly endure in our heads, we desperately want to know that something exists beyond our current state of disillusion. We want to embrace the mystery of God, but we also want to know that he is real, and that He exists; in a secular world, that epiphany only occurs when we miraculously “come-out.” Then, we are supposedly born-again into a new life of profound meaning and happiness. But, those same young people also have a great desire to be guided, to be nurtured, and to be loved. In males, this almost unquenchable longing propels many towards the abyss of all-male exclusivity. And, herein in lies the devil’s last joke – that in a world without women, there are no real men to be found. Everything becomes a mockery. Nevertheless, most go on looking. The tragedy of it all, that in their earnest search, they eventually find nothing.

When the Lord Jesus Christ carried me from that life, he unbound my hands, and tended to my many wounds. Once I was well enough to walk, for a while, I drifted from one Catholic parish to another, where I often felt as if I materialized back to the feckless boyhood years I spent in the Church during the 1970s and 80s. But, I wanted to believe. Only, the priest and the countless ministers surrounding him during Mass, treated so casually what was supposed to be the Body of Christ – I couldn’t believe it. Then to make matters worse, the same priest told me that I had been “born gay.” In that moment, I could almost sense something begin to tighten around my throat. Would I ever escape from the sheer mediocrity of a sexual identity? Could I overcome and transcend my past? Would I ever know God?

The solace, the reverence, the devotion, and the beauty that I had always sought in my life – I found within Tradition; especially at the Tridentine Mass, for the first time, I walked into a church and found it strangely silent, I saw devotion in the eyes of a family, in the loving embrace of a father who tenderly held his son while trying to kneel and hold the boy with one hand and a missal in the other, in the reverence and care of the priest whose hands alone were anointed for such a glorious glorious task as to administer the Body of Christ, in the Truth and compassion which issued forth from the lips of the same priest who both represented the manhood and the Mercy of the Son of God, in the love I discovered for the virtuousness of femininity as embodied in the Blessed Mother, and in the joy I finally felt when receiving the Lord into my body. I had embraced the mystery and the mystery embraced me.

*2014 HIV Infection Risk Prevention, and Testing Behaviors in Men Who Have Sex With Men.