“A dungeon horrible, on all sides round,

As one great furnace flamed; yet from those flames

No light; but rather darkness visible…” – John Milton, “Paradise Lost”

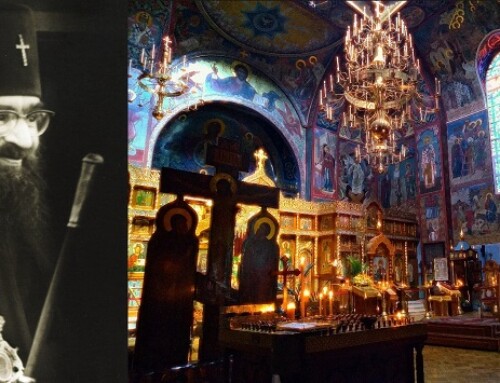

There is an extraordinarily haunting and even somewhat terrifying scene in the 1931 film “Mata Hari.” Played by Greta Garbo, Mata Hari was a real-life exotic dancer and spy who worked for the Germans during World War I. In the midst of her various intrigues, she ended-up falling in love with a naïve and young Russian lieutenant – Alexis Rosanoff played by the tragic Roman Navarro; the homosexual Navarro was murdered by a pair of male prostitutes in 1968. Before she will even consider being his lover, Mata Hari demands that Alexis extinguish a candle that burns before an icon of Our Lady of Kazan that he keeps in his apartment. The integral moment occurs when Mata Hari reclines seductively on a couch below the icon and the burning vigil light while the lieutenant stands above her. At first, he refuses; having stated that his mother carried the icon on pilgrimage from the shrine at Kazan. But like the majority of the men who witnessed her erotic dance before a large statue of the Hindu goddess Shiva – the lieutenant is seemingly possessed by his love (or overwhelming lust) for Mata Hari. In fact, he says that he “worships her.” After a few prolonged seconds of almost tortured consternation, he finally blows-out the flame and everything fades to black.

Why is this important? In a sense, Our Lady of Kazan and Mata Hari represent opposing “icons.” In fact, the secular use of the term “icon” or “iconic” is often associated with Hollywood and the entertainment industry. In the so-called “Golden Age” of motion-pictures in the United States, one of the most instrumental figures in the propagation of Tinseltown glamour was the photographer George Hurrell. In his images, oftentimes closely cropped to the face, film stars appeared angelically luminous when set against a stark black background. During the depths of the Great Depression, a plethora of movie magazines were published – filled with pictures of the stars and details about their personal heartaches and triumphs. They were read like hagiographies; and the stars became secular saints. This phenomenon has survived particularly well-intact in the “gay icon.” Usually determined or mistreated women who maintain a strong following among gay men; they include: Joan Crawford, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe, Princess Diana, and Beyonce.

“But don’t you understand that it’s a holy lamp? That I swore to keep it burning?” – Lieutenant Alexis Rosanoff, “Mata Hari”

In the 1970s, when I was a boy, there was a large resurgence of superhero culture in the West. The first great outpouring occurred in the late-1930s to early-1950s with the advent of comic book and newspaper strip protagonists such as Superman, Flash Gordon, and Buck Rogers. Most of these characters were also spun-off into feature films and most notably – movie serials. About 25 years later, they returned with big-screen adaptions of both Superman and Flash Gordon, and on television with Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, The Amazing Spider-Man, and The Six-Million Dollar Man series. For a lonely and shy young man, these films and tv shows were almost sacred. In them, were preserved the image of the incredibly masculine and courageous man, who compassionately protected the weak and vulnerable. As I would later find out, for the baby-boomer generation, the group of gay men who moved to San Francisco before me, the rugged and fearless Hollywood cowboys of the 1950s were a similar sort of idol. We all spent many hours of our childhood dreaming of being rescued by such men. They became our imaginary saviors. By the time I reached my teens, I thought that a human redeemer was truly accessible to me.

Unlike the devout Russian lieutenant in “Mata Hari,” it wasn’t a difficult decision to leave behind the one pseudo-sacred icon that was implanted into my mind during the 12 years of Catholic parochial school: the clown-faced hippie-Jesus from the movie “Godspell.” I thought of Christ as a hopelessly feeble and useless loser. In San Francisco, despite the ravages of AIDS, a few formidable men were still withstanding the onslaught of discrimination and death. I wanted to be among them.

“This first dogma introduced from the new religion…there is no truth.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose

In 1950s and 60s San Francisco, an incessantly curious and incredibly intelligent young man searched through the burgeoning environs of the counter-culture for the meaning of life. He did not find it in the Beatnik scene, nor amongst Western devotees of Buddhism, or within homosexuality. Early on, Fr. Seraphim Rose understood the essentially empty nature of modern American consumer culture. In this meaningless environment, with our instinctual desire for the transcendent, mankind has grasped onto a series of feeble replacements. Fr. Seraphim wrote that all of these political and social movements are a result of: “Western man in his falling away from God and trying to find the new religion.” For myself, “the new religion” was the gay liberation movement. When I was a kid in the last-1970s and early-80s, they made some big promises. Like the old advertisements from Charles Atlas, depicting a skinny guy getting sand kicked in his face at the beach – by some brawny and confident muscleman, you too could be a real man. For me, at the YMCA, forever enshrined into disco history by The Village People, I believed that I could finally realize my greatest aspiration. And, we had our own icons; i.e. Andy Warhol’s gigantic “iconic” headshot images of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis.

Shortly before his death in 1982, Fr. Seraphim discussed the role of Communism as a precursor to the Antichrist. He said: “…in the West there is a spiritual vacuum, and when this vacuum is present Communism simply marches in, taking one little territory after another until, at present, it has conquered nearly half the world.” But today, “Communism” could be replaced with any other niche phenomena. For instance, in 1997, only 27% of Americans favored same-sex marriage; in 2021 – that number had risen to 70%.

Arguably no other movement in modern times has made such an immediate and enormous impact on public consciousness. And it all really started in the 1970s. Symbolic of the entire era, the 1978 single from The Village People, “YMCA,” heralded a new age of sexual freedom and liberation for a generation of men who sought out acceptance and affirmation from a world that previously shunned them. Its was the same lie sold to another group of disaffected youths – with Scott McKenzie’s 1967 ode to the Summer of Love – “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” For many of those who made the trek out West, in the 1960s, they often found a wasteland of drug abuse, manipulative cults, and sexual exploitation. A decade later, the great gay migration to San Francisco foreshadowed the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. And, as an example of just how deep the bottomless pit remains inside the core of each lost soul – even though I somewhat understood the inherent risks that awaited me in the gay male community, I went there anyway. I thought I had nothing else.

In a sense, I was blind. I wasn’t visually impaired, but I also couldn’t see. Through the denial of truth, all of us can cloud our own vision to the point of total darkness. After being groomed – and told constantly that “God made me this way” – I continued to brainwash myself. Despite everything going wrong – I persistently repeated the same gay-mantra: “It will get better.” This level of self-delusion was explored beautifully in “The Brothers Karamazov” by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Oftentimes, the voice of truth and reason in the story comes from the Russian Orthodox monk – Father Zosima. In one of his more eloquent statements, Zosima says:

“A man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point where he does not discern any truth either in himself or anywhere around him, and thus falls into disrespect towards himself and others. Not respecting anyone, he ceases to love, and having no love, he gives himself up to passions and coarse pleasures, in order to occupy and amuse himself, and in his vices reaches complete bestiality, and it all comes from lying continually to others and to himself.”

I lived that firsthand. The lies that were fed to me when I was a child became what has been called in the early 20th century as “my truth.” But this “truth” was based on an illusion. And I would do anything to uphold that edifice of legitimacy. Supposedly – we were all destined to be there. But as the body count around me began to increase. I started to doubt. Was I born to die? Or had I sold my sold for the proverbial three magic beans? I had been duped. At that moment, I began to see. Although my eyesight was far from perfect, I could suddenly discern certain shadowy figures that surrounded me. Had they been there for years? Probably. I just didn’t notice them.

This literal blindness is dramatically portrayed in “Mata Hari” when Alexis is injured and loses his sight. In the meantime, Mata Hari has been captured and sentenced to death. As a last request, she gets to have a final meeting with the one man she sees as her only true love. But their relationship is a lie. As part of the bargain, her executioners agree to maintain a certain charade: that Mata Hari is not housed in a prison, but a hospital where she is about to undergo a life-saving surgery. Everyone plays along when Alexis arrives. He thinks she is being taken to the operating room, while in reality she is being marched to the firing-squad. The scene is simultaneously poignant and pathetic.

“Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.” ― Fyodor Dostoevsky, “Crime and Punishment”

In the film, the motivations behind Mata Hari becoming spy are never really explored. Although it’s a life of evident intrigue, glamour, and adventure – like Lestat’s cult of vampires, once initiated, she unable to leave. In some way you are permanently transformed. In one scene with Alexis, she says: “I am what I am. You don’t know me. Go away and forget me.” In this, I am reminded of Gloria Gaynor’s gay-anthem “I Am What I Am.” In a sense, her career (lifestyle, sin, orientation) has marked her for life. She is trapped. And how does one buy back their soul? Mata Hari’s spymaster quipped: “The only way to resign from our profession is to die.”

Long before the advent of emails or text-messages, those of earlier generations were often voluminous letter writers; certainly, among them was Fr. Seraphim Rose. Before his conversion to Russian Orthodoxy, usually with former college friends, Fr. Seraphim philosophized about the extensional questions of life, death, and meaning. In one of his most profound letters, he wrote:

The punishment of sin is sin. Pain is the greatest blessing, for it awakens man from his self-hypnosis, the self-delusion that can take any earthly goal — be it crude, such as sex, food, comfort, or subtler, such as art, music, literature — as final. The desire for these things fails, and man becomes weary. Then: he fades away or kills himself; or he undertakes the path to deliverance, salvation…Disease, suffering, death — these are reminders, convenient reminders, that man most profoundly is not of this world. In an age of pleasure, God is seldom seen.

In my own conversion story, I reached a similar conclusion; though I was never able to articulate it in such an eloquent way as Fr. Seraphim. Instead, I just lived it. One day, I was given a rather stark set of choices: life or death; salvation or damnation; God or the gutter. The world of freedoms that I thought I enjoyed, had become my prison; my “punishment.” The physical and mental torment which I endured on a daily basis was so intense that I could no longer sleep. But it also pulled me out of my daydream existence. I am reminded of a powerful scene from one of my favorite childhood films; in “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom,” Indy falls under the spell of a murderous priest of the goddess Kali; in order to awaken him from this evil trance, his faithful young sidekick burns Indy with a torch. That moment of searing pain brings him back to his senses. For me, it was years of agony. That’s how deeply I had been brainwashed. The promise of profound consciousness and fulfillment through self-realization and sex proved strong, but disastrous; on a societal level, this has become evident in the plague of clinical depression, antibiotic-resistant STDs, and drug overdoses. In the end, the meaningless actuality of idle, temporal, and worldly pursuits only creates disappointment, bitterness, and anger.

From my own experience, a life of sin can end in one of two ways; as Fr. Seraphim wrote, the eventual realization that the world makes empty promises could awaken someone from their “self-hypnosis.” Consequently, we are humbled, sometimes physically and psychologically shattered, and we are left alone. The party-bus moves on without us. Then, we must make a monumental decision – to abandon our previous ways of thinking and perceiving the world and ourselves or we can jump back into the parade and follow the crowd until it all comes to an end. For those who refuse to let go of their pride, the celebration eventually turns into a funeral procession.

At the end of “Mata Hari,” the film remains a performance within a performance. Mata Hari is playing a part – as the exotic dancer who is actually a spy; but she is also playing the part of herself. But she is lost in an image. In the West, the 2lst century has become a sort of 24-hour kabuki theatre. Warhol’s 1968 prediction that “everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” has proven true. On social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, ordinary people can become “stars” by endlessly posting almost every occurrence from their everyday lives: from pictures and video-clips of what they eat and wear to semi-pornographic selfies. The more outrageous the better. But none of it is real. Consequently, the realm of make-believe has spilled out into the real world. Like the ”face filters” on Instagram that can superimpose flower-crowns, animal ears, or devil horns onto a selfie, people have begun to reimagine their identities in order to conform to an online persona.

The final few shots from “Mata Hari” are closeups of Greta Garbo as she is being taken away to her execution. Much of the earlier artifice is now gone. The heavy makeup, the costumes, the gowns are replaced by a brightly illuminated face and a simple black floor-length cape. In death, the lies are finally destroyed. Light returns. One day, we will all have to confront that same moment; when we are stripped bare. And we only have our soul to offer up to God. Hopefully, we haven’t sold it – for nothing.