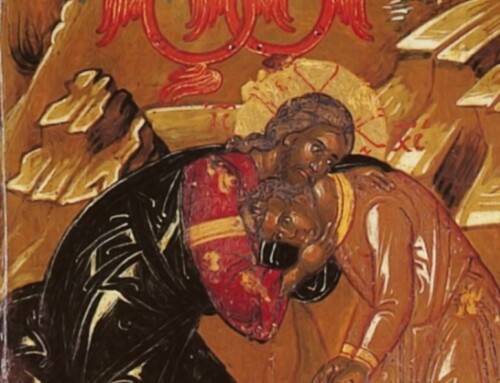

Despised, and the most abject of men, a man of sorrows, and acquainted with infirmity: and his look was as it were hidden and despised, whereupon we esteemed him not. – Isaiah 53:3

Since childhood, I had always been drawn towards the margins, the periphery, the fringe of society. Perhaps, it would be more accurate to state that I was cast-out at a young age and instinctively moved to the sidelines – as I had nowhere else to go; at recess, the other boys didn’t want me around; I was awkward and afraid; but I desperately wanted to belong.

When I got out of my forced confinement in high-school, I almost immediately ran away to San Francisco; in the late-1980s, it wasn’t particularly cool to be a gay man. Many people were afraid to touch (or even be around) a male homosexual. The fear of AIDS was palpable – some were too frightened to bury an AIDS victim. But I didn’t care; the fear of life-long alienation and loneliness was greater than my fear of a deadly disease.

Even in the midst of a pandemic, I didn’t feel alone or disregarded anymore. I was oddly elated; my mind-set was almost perfectly articulated by one of the gay men in the 1993 film version of Randy Shilts’ “And the Band Played On:”

“Now for years and years and years people in my hometown were telling me I was a freak because of my sexual orientation, until I came to San Francisco, and I found a community of freaks just like me.”

I thought, I finally found a place where I belonged. Somewhere over the rainbow; a Technicolor wonderland where everything was extreme, but celebrated. Even the Catholic priests – located on the outskirts of the Castro District, were also pushing the envelope. They performed the mundane, which became the extraordinary in these unusual circumstances; for instance, they buried our dead and blessed our marriages. I grew-up around effeminate priests and religious brothers, but all the multicolored stoles, openly affected behavior, and incessant gay advocacy caused me to reexamine a painful episode in my own life – perhaps, that priest who told me that “god made you gay” when I was just sixteen, maybe he was being kind; he was trying to guide me. Regardless, these priests appeared overfriendly to the point of looking desperate and lecherous; they made me uncomfortable; so, I attended a couple of funerals and gay weddings; but I wouldn’t speak to another priest for almost a decade.

Years later, once again, I found myself on the peripheries. In the meantime, gay priests, LGBT-affirmative pastors, and the parishes and ministries they helped to promote had decidedly moved far beyond the fringe of the Church to occupy central positions of authority and prestige. However, banished to the scary parts of town, the growing “traditional” movement that often centered around a devotion to the Tridentine Mass, were amassing a devoted following. There, I found large families (headed by a mysteriously religious father) that willingly sacrificed their comfortable pew in a neat suburban neighborhood parish for a crowded spot in an old and drafty building; reminded me of how English author Evelyn Waugh described his conversion from the splendor found in the hollow high Anglican Churches to Catholicism: “The medieval cathedrals and churches, the rich ceremonies that surround the monarchy, the historic titles of Canterbury and York, the social organization of the country parishes…all these are the property of the Church of England, while Catholics meet in modem buildings, often of deplorable design.”

For the most part, the priests who ministered to these outlying members of the Catholic flock were themselves from small orthodox religious orders. But I also met a number of priests from local dioceses who were attracted to traditional Catholicism. Like me, many of them came of age during and immediately prior to the liturgical experimentation of the 1970s. Sequestered in out-of-the-way parishes, they were able to sometimes sneak-in a bit of reverence and tradition into otherwise bland and insipid liturgies that were dominated by strumming guitars and pushy female eucharistic ministers. I admired these priests for their tenacity, but also became angry with them – for something that I perceived as blind obedience. Due to their “rigid” adherence to orthodoxy and the truth, they were often reported to the chancery by vicious and vindictive lay members of the parish – usually women. For their apparent pastoral inflexibility and stubborn unwillingness to adapt the liturgy to better accommodate a changing society, these priests were resoundingly persecuted and punished – by fellow priests and their own bishops. This often-subtle form of abuse was incredibly damaging – both psychologically and spiritually. When one of them was sent to a notorious gay seminary for “re-training,” I visited him during his imprisonment. He described being forced to watch episodes of “Will & Grace” in order that he may more fully appreciate the homosexual experience; in addition, he endured endless lectures on the usefulness of the Enneagram of Personality; and repeatedly rebuffed the unwanted advances of another priest. I thought, the pressure of this environment was driving him mad – he worried about others listening-in on his phone conversations; in hindsight, maybe he was so crazy. Another priest shared a rectory with an openly gay pastor who sometimes loudly fought with his same-sex lover; one day, while I was talking to Father in his office, their upstairs quarrel spilled out into the street; I audibly uttered an expletive – “**** this.” He reprimanded me. In me, he thought there was something worth saving. Finally, I met a kind-hearted but somewhat naive priest who was driven to the edge of suicide due to a lack of support from – his own bishop. I didn’t speak to him for some time because of a disagreement we had, but one day he unexpectedly called me; he couldn’t take it anymore. He thought by simply being kind to the obstinate, he could change hearts and minds; it didn’t work.

With only a few exceptions, those diocesan priests who were unashamedly orthodox and traditional were the objects of derision from more progressive Catholics and subjected to often mean-spirited surveillance from the local ordinary. Sometimes assigned to poorer and less influential parishes, regardless, these men often gathered a following of faithful lay-people around them that was not based on any cult of personality, but solely due to their strong leadership which manifested in an outward sign of personal sanctity. This was in sharp contrast to the superstar priest known for his amicability and prodigious ability to fundraise. They reminded me of those semi-closeted priests I met in the Castro – in my estimation, they were more concerned about parishioners being happy than holy. Later, I found out – you can be both. The apparent loyalty and joyfulness of the traditional priests’ flock and his ability to bring an impoverished and near bankrupt parish back into solvency only increased the animosity from other diocesan priests who had to deal with dwindling numbers in the pews and the constant need to hustle a smaller number of wealthy demanding donors.

This almost unceasing oppression from within has created saints, but also victims. Men who have not been able to withstand the pressure and the devastating level of scrutiny, have been crushed. The hypocrisy in the Church is incomprehensible; while well-connected priests rose through the ranks, even into the episcopate, though their immoral (even criminal) behavior was well-known among their colleges, humble priests with compassion and love for the people were persecuted. At least in the US, I believe the system of the diocesan priesthood within the Catholic Church is hopelessly broken; this situation is entirely due to the weak, lazy, and thoroughly corrupt hierarchy. The bishops have promoted the dissolute and tyrannized the virtuous. Tragically, this scenario has played out a global scale with the ascendancy of the utterly compromised Cardinals Cupich, Tobin, and Farrell. In retrospect, I would argue that the only way forward will include the instrumental involvement of religious orders that have remained faithful.

“He (Scipio of Rome) did not consider that republic flourishing whose walls stand, but whose morals are in ruins.” – St. Augustine

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Catholic Church, specifically the monasteries, became citadels of semi-stability during the chaos of political and societal collapse. Surrounding the monasteries, small villages and then towns slowly arose out of the rubble. This situation occurred partly due to necessity – the need for the defenseless peasantry to obtain protection and for merchants to find a central location to engage in their trade.

Currently, myself and others have huddled around stalwart and courageous priests or similarly devoted religious orders; we have sought a safeguard from an increasingly malevolent world and support from a like-minded community. In this sense, the “Benedict Option,” made famous by author Rod Dreher, is a totally rational alternative to the madness that seems to have taken over many parishes and dioceses in the US.

Only, I haven’t remained secluded in a faraway bastion of old-fashioned Catholic piety, I have tried to engage the culture – even as it crumbles all around me. For some unknown reason, I am continually finding myself back in Babylon. At times, I think there is a distinct danger that those isolated in Elysium will look down with contempt upon the misfortunate casualties of weak leadership; some might also come to believe that they deserve to be here, or they arrived at this place through their own volition. We certainly have the power of agency in our lives, but everything would have turned-out so differently for me – if someone had not suggested to me that I checkout a “Latin Mass” at an old parish in a depressed area of downtown Sacramento; that day, I could have walked out of yet another three-ring-circus Mass, never to return to the Catholic Church. Early on, I learned that sometimes we are at least partially a victim of circumstance; during the age of AIDS – friends who were far less promiscuous than myself suddenly got sick and died; I could have left with that guy, but my friend did instead.

Rather than abandoning an incredibly large segment of humanity, over the years, I have considered myself a would-be “Johnny Appleseed.” At various “Pride” events, parades, and gay sex fairs, I show-up (frequently with a small band of dedicated volunteers) to share the hope and truth to be found in Our Lord Jesus Christ. With hundreds of thousands-to-millions in attendance (and the constant sound of dance music throbbing in the background) it is nearly impossible to have a meaningful conversation with anyone; but a prayer only requires a couple of seconds. Here, on ground that appears irreparably parched and salted, we plant seeds that may or may not (one day) begin to grow.

Be not deceived, God is not mocked. For what things a man shall sow, those also shall he reap. – Gal. 6:7-8

Now, after 20 years, I look back at what those priests had to endure and I know that their suffering was not in vain. If they helped one person, they made a difference. And they did – they helped me. As a result, I was able to begin the healing process, find some inner-strength, and then gain enough courage to offer comfort and kindness to someone else; part and parcel with this process was my eventual ability to stop feeling sorry for myself. One of those honorable and harassed priests once gave me some inspired advice – end the day with a recounting of how God blessed you during the past 24 hours. My first impression of this suggestion: I have nothing to be thankful about; up until this point, my life had been a series of traumas from which I barely survived. On a fundamental level, I think I blamed God for much of it. But through suffering, no matter the initial fault or the circumstances, I was able to appreciate the truth because of my past. When you have lived with the lie, accepted it, made it an integral part of your being, and then watch it collapse in front of you – it’s sometimes easier to recognize error while experiencing the pain of desolation and remorse.

Thank God for those few and faithful priests who served as living storehouses for the sanity of truth – much like the monks after the Fall of Rome; they are often the last hope for the hopeless; they have truly become missionaries to the marginalized, the forgotten, and the abused. But they have lifted up those who are truly ignored by the bishops and other priests; not by writing meaningless books, not by pressuring the Church to change its teachings, and certainly not by confirming us in our woundedness – God didn’t make us this way. I wasn’t born a “freak.” Through their own commitment to endure personal suffering and through their own fidelity to the truth, these men have genuinely given us hope. For such priests, I think their reward will be great in heaven; as for the bishops and cardinals – they represent a lie. They will reap what they have sowed: cowardice, deceit, and neglect.

Pope Benedict XVI wrote: “Truth and justice must stand above my comfort and physical well-being, or else my life itself becomes a lie.”

Beautiful!