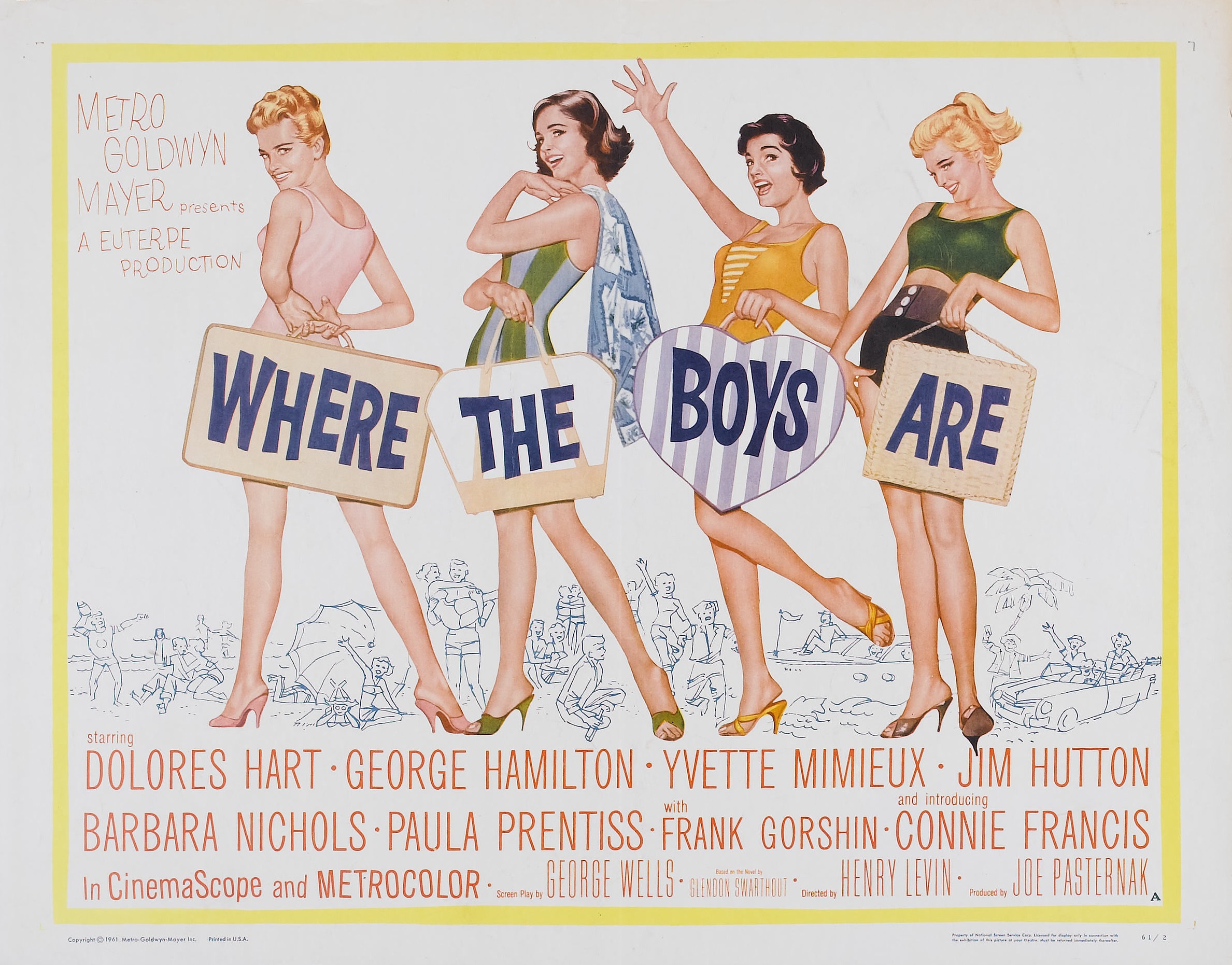

I have been interested in the life and career of actress Dolores Hart ever since I saw her in the 1961 film “Francis of Assisi.” I thought her performance as Saint Clare was exquisitely sensitive and that she looked simply luminous. I became all the more intrigued about Hart when I later learned that shortly after completing a few more films, she left Hollywood to become a Benedictine nun. I was saddened though to find out that half of the ten motion pictures she appeared in were unavailable on either VHS or DVD. One notable exception is “Where the Boys Are” released in 1960. At first, I thought the film was a typical “beach” movie. I was so wrong.

“Where the Boys Are” prefigured the height of the “beach” movie craze by a couple of years. Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello would not appear in their first chapter of the popular series of beach-party films until 1963. It is unfortunate that “Where the Boys Are” later became associated in the collective unconscious of the movie-going public with the Frankie and Annette films and their subsequent cheap rip-offs such as “Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1965)” and “The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966).” The Frankie and Annette films were all distributed by American International Pictures which became famous for making low-budget horror and teen exploitation films. With the exception of Avalon and Funicello, these films starred pretty but talentless non-actors. The comedy was light, the musical numbers forgettable and the production values almost non-existent. They made for a carefree afternoon at a matinee, but none of them ever really went anywhere.

Though for the purposes of this essay, I would like to first examine the film that probably got the whole genre started in 1959. The film is “Gidget,” staring Sandra Dee in the most glycemic shock role of her career. Unlike the beach films of the later 1960s, “Gidget” was released by a major studio (Colombia Pictures) as a vehicle for one of it’s newest stars. The film also featured Cliff Robertson who had already given a great performance in the dramatic movie version of William Inge’s play “Picnic.” Gidget was not an exploitation film, but it did appeal to teenagers who were the film’s target audience. As in most of her movies, Sandra Dee plays a relatively naive and sheltered middle-class girl on the verge of womanhood. In “Gidget,” she falls in love with a surfer (Moon-doggie) played by James Darren. Cliff Robertson’s character (the Big Kahuna) takes a liking to Gidget and allows her to hang around him and his group of surf-bum followers. One of the guys gets a bit too fresh with Gidget, but Moon-doggie comes to her rescue. The film’s most interesting line occurs after Gidget gets in an argument with her parents. Her father and mother want her date to pick her up at their house. But Gidget wants to meet him at a downtown cocktail lounge. Her father goes nuts. Gidget storms out of the house and her mother says (as we hear the sound of car tires peeling out of the driveway:) “she’s taking the car!” Later in the film, in another pivotal scene, Kahuna notices that Gidget is trying a bit to hard to attract Moon-doggie, so he arranges to scare her with a mock seduction encounter at his beach-shack. It works, and she flees with her innocence intact.

The reason for my examination of “Gidget” is that I now want to contrast it’s view of dating and sexuality with “Where the Boys Are;” which I will now refer to as WTBA. Where “Gidget” only coyly splashes around the issue of sexuality in the 20th century, WTBA jumps unapologetically straight in. But we must remember that “Gidget” is a direct product of the 1950s studio system’s idea of on-screen comedy. The film’s writers would try to come as close as possible to the idea of desire while always staying in the cool sphere of purity. That is why Marilyn Monroe skyrocketed to fame in the era. She was the perfect combination of hot deliberation mixed with irreproachable cluelessness. It was not until Ursula Andress crawled out of the sea in a wet and barely there two-piece, in the first of the James Bond films: “Dr. No (1962),” that audiences started to crave more explicit sex and violence.

The only time “Gidget” takes a serious turn is when Dee absconds with the family car. The dynamics of automobiles and teenagers in the 50s I find endlessly fascinating. In the 1950s, for the first time, teens had direct access to cars. Before, automobiles were primarily the exclusive domain of professionals and working men. The Post-War boom, the emerging wealth of the middle-class, the rise of suburbia, and the affordability of mass-produced cars, made having an automobile a new necessity. The availability of cars also dramatically impacted teenage sexuality. Automobiles opened up a new world for teens. Automobiles provided a space for teens to drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes and to have sex. The age of innocence was over. The phenomena of “car-dates” took courting out of the family sphere. For example, if you look at the 1950 film version of “Father of the Bride,” a very different family dynamic is represented. Just ten years before WTBA, Elizabeth Taylor portrayed a woman who still remained protected as all dating or courting only occurred within the restricted and controlled confines of the family. Prospective suitors all came from the family’s immediate social circle. The family, especially the father, vetted all new-comers. Casual dating, let alone sex, was unheard of. Courting would almost always lead to marriage.

As far as I can tell, “Where the Boys Are” was the first major studio film to seriously deal with the issue of premarital sex. And the film wastes no time. As an aside, the 1953 film “The Moon is Blue” delved into the topic of female virginity, but it was all for comedic effect. In WTBA, the topic is discussed in the opening scene. But first, I would like to digress a bit and examine the film’s title song. Sung by Connie Francis, “Where the Boys Are (the song)” was written by Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield. The song is remarkable, besides for the sonorous vocals by Francis, in that is was not a typical teen-movie film song. Again, this emphasizes the fact that WTBA was not your everyday beach movie. At the time, as with the other films concentrating on teenage life, beach movies relied heavily on music by The Beach Boys, Dick Dale or the other surf bands. Like Sedaka’s other two major writing hits, “Who’s Sorry Now?” and “Breaking Up is Hard to Do,” WTBA is infectious pop with an air of unrequited longing. Like the film itself, there is something sad and haunting about it that is unforgettable.

The film opens at a Midwestern women’s college during a blizzard. Merritt, played by Dolores Hart, slips down an icy step on her way to class. The name of the course: Courtship and Marriage. As the later-middle aged professor drones on, we see Merritt falling asleep at her seat. Also in the class with her is Merritt’s friend Melanie. Melanie is a pretty blond. She is a sheltered and shy girl. She does not have the bubbliness of Sandra Dee’s Gidget, but comes from a similar back-ground; i.e middle-class, vulnerable, and inexperienced with men. The actress who played Melanie, the always fragile looking Yvette Mimieux, would be perfectly cast, later that same year, as the child-like futuristic ingenue in George Pal’s science-fiction masterpiece “The Time Machine (1960).” Melanie grew up near the college and has never been away from home. In this scene, she wears a conservative turtle neck sweater. Merritt is the more glamorous looking of the two. She usually wears her hair in a more sophisticated bun than Melanie’s loose bobbed style. While Melanie is noticeably without makeup, Merritt is an exquisitely perfect cover-girl.

As Merritt dozes, we hear the professor in the background throwing around terms such as: “unrestricted contact with the opposite sex,” “random dating,” and “premature emotional involvement.” The professor notices the inattentive Merritt and asks her a question. Merritt self-voluntarily mentions “Dr. Kinsey” and the professor cuts her off. Merritt then cuts to the heart of what she thinks this whole course is about: should a girl “play house before marriage?” The professor haughtily says, “I would be afraid to ask your opinion.” Merritt defiantly states, “my opinion is yes.” Melanie looks quickly over to Merritt with shock and astonishment. The professor quickly ends the class.

Beginning in this scene, Dolores Hart is expertly creating a completely new type of American young woman. One who is intelligent and instinctual, beautiful but not conceited, young but not gullible. With her portrayal of Merritt, Hart predated the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s by over ten years. But what makes the character even more extraordinary is that Hart is able to develop her in the short span of a ninety-nine minute movie. As I will explain, with experience, Merritt’s opinions drastically change. But in essence, she still remains a feminist. Not the bra-burning feminist type of the next decade, but a truly feminine persona grounded in all that is unique and special about women. Merritt’s exceptional force of personality does not go unnoticed by the other women. Still pondering her outburst in class, Melanie asks Merritt: “did you mean it?”

Wishing to escape the frigid north, Merritt, Melanie, and two other friends: Tuggle and Angie, head to Fort Lauderdale for Spring Break. Tuggle is a statuesque but awkward woman and Angie is confident and sassy but peculiarly unpopular with men. On the way south, the women pick-up a hitch-hiker; a boy nicknamed TV. He is an affable if not immature college guy that Tuggle takes an immediate liking to; namely because he is also unusually tall. Once in Florida, Melanie wastes not time and begins to recklessly make friends with any cute “ivy league” boy she can find. The others watch in amazement: “she makes friends fast.” While talking to one of the boys, Melanie says: its my “first time away from home.”

From the get-go, we see the naive Melanie opening herself up for abuse. Armed with only Merritt’s protestations about free-sex, she repeatedly tells the others some story she overheard about a young women who met a boy while on Spring Break and they were married only a few days later. The others quip that the baby came less than 9 months after. This goes over Melanie’s head. But Melanie is not only unworldly but also needy and desperate. She seems to be trapped between the world represented by their professor; a world that Merritt described as “old fashioned” and the new age of sexual freedom. To traverse this new world is a dangerous feat. As we shall see, the more street savvy Merritt is well-equipped to survive anything the male gender can throw her way. Poor Melanie, as many girls do today, gets quickly used up. In the world of “Gidget,” Moon-doggie or Kahuna would have come to Melanie’s rescue. There the boys were slightly lotharious, but always essentially harmless. In the real world of WTBA, no hero was waiting and the boys – much more dangerous.

After only a few dates, Melanie spends the night with a boy she just met. Unlike the films of today, nothing is shown of their tryst; WTBA is a far more intelligent film than today’s gross-out teen comedies such as “American Pie.”. The only clue: the next day Melanie says to the boy, “you won’t tell anyone?” Later that morning, the rest of the women fall out of bed to find Melanie sitting by the window. She is sullen, tired-looking and smoking a cigarette. They have never seen her smoke before. For Melanie, once the first barricade has been broken, the rest of her inhibitions fall away. During the rest of their vacation, Melanie no longer exhibits the carefree attitude of the other still virginal women. She is entering the realm of those who are bitter and betrayed. It has been my belief that most women give sex to receive love; and that men give love to receive sex. Of course, this is not true for the devout Christian, but still true to the world at large. And when women give sex and do not get love back, they are deeply wounded.

Meanwhile, by the poolside at the women’s hotel, Tuggle is putting up a valiant fight. TV is trying desperately to get to first base with Tuggle. She smartly plays hard-to-get. So far, all of their dates have been drinking binged chit-chats at a local bar. The common thread is his persistence. Whenever he starts to talk about sex, she quickly changes the subject. Also, her body language and general demeanor speaks volumes. Her clean and easy sureness is in opposition to Melanie’s down-cast bashfulness. Frustrated, TV says bluntly: “are you a good girl?” Tuggle confidently says “yes.” Their innocent rendezvous comes to an abrupt end. Later, when alone with the others, she states that she will find a man “the chaste way.” To the other sad extreme, after getting what he wanted, Melanie’s first lover has moved on. In another of her unfortunate moves, she is now dating one of his friends.

The last of the women to meet a boy is Merritt. Her eager admirer, Ryder, is a well-to-do Easterner whose family owns a large beach-front home and yacht. He takes her to the boat, they both drink and she quickly verges on the edge of tipsy. Wanting to stay coherent and in control, she stops. Right away, he pops the question and asks Merritt to spend the night on the boat. She is a bit taken aback. She says she needs to find a new “classification” for him. She explains that she labels men as either: “sweepers,” “strokers,” or “subtles.” The subtles, she says, always find a way to introduce the topics of “erotic literature,” “Freud,” or “The Coming of Age in Samoa” into the conversation. This interchange is crucial for its sophistication, but also for the fact that it is between two young people. Today, I do not think any average teenager could tell you who Freud is or even heard of Margaret Mead let alone read one of her books. Merritt’s mentioning of Margaret Mead’s book is interesting also because in “The Coming Age of Samoa” Mead argued for a liberalization of sexual mores in the West. In addition, the level of intellectual acuity in polite conversation has certainly taken a dramatic dive. And it is in this film, where society is first wrestling with the coming sexual revolution, that we see the beginning of our youth’s downward slide into sexual degradation and mental lethargy. Because, as our morals have become compromised so goes the mind.

Later, when Merritt and Ryder talk again, the conversations are once more dominated by the subject of sex. Here we start to see a shift in Merritt’s attitude. She says that no girl enjoys being labeled as promiscuous even though she might be. Again, for women, sex is much more about intimacy and love while men are often fixated on the mechanics of sex. I have found this in popular culture: where women are the sole purchasers of “romance novels” and the relative absence of pornography marketed to women. Men tend to be universally image fixated, hence the absence in history of a female Michelangelo. Ryder further widens the gap between them by claiming that sex is no longer a matter of “morals.” It’s like “shaking hands” he says. This attitude towards sex is rare in women, henceforth the near impossibility of women taking part in anonymous sex or cruising public toilets. Both practices are widely acknowledged by males especially in the gay community. At their every meeting, Ryder tries to escalate the level of intimacy, with kissing going to necking then open-mouth kissing. Merritt finds that everything is moving far too fast for her. In the end, Merritt is done and wants to be taken back to the hotel.

Back at the hotel, Merritt runs into the wayward Melanie who stumbles drunkenly back from a date. Merritt scolds her for acting so irresponsibly. Melanie is rightly shocked, as it was Merritt “who preached on the subject” of premarital sex. But for Merritt all that talk was theory. Melanie actually put it into practice. And the reality turned out to be much more messy. This is because Melanie gets caught in the trap of perpetual promiscuity. Once you’ve taken the leap you can’t then go back and regain your virginity or your innocence. As we see in the film, everything becomes desperate for her. She is knocking on the boy’s hotel room and calling them on the phone. She is the one seeking them out. This is a complete reversal of the traditional sexual roles. She has been used and has nothing to show for it: no promise, no commitment, no love.

Later that night, the rest of the women and their dates are at a sort of upscale tourist Tiki-bar. The entertainment provided consists of an underwater mermaid show. Imagine Esther Williams in a fish tank. The actress in the swimsuit is Barbara Nichols. She was a B-film actress who perfected a cheap and brassy Marilyn Monroe impression that oozed sex but lacked the original’s gentle spirit. The name of her character in the film: the laughable but semi-erotic sounding Lola Fandango. When he sees her, TV’s chin hits the floor. He exclaims, “what lungs.” Feeling completely worthless, Tuggle incredulously stares at him in amazement. Then, in the film’s most famous scene, the infatuated and drunk TV jumps into the water tank, gets tangled on some type of underwater ladder which then leads to everyone else jumping in to save him.

The party then moves to the beach, where Lola performs a mock striptease and TV looks on admiringly. Tuggle is in the background doing a slow burn. But her anger then turns to tears of pain. The tawdry Lola has captured his lust, all-the-while Tuggle had been trying to seize his heart. Although TV acts abominably, his struggle mirrors that of Melanie’s. The struggle between the world of sensuality, represented here by Lola, and the realm of the soul. Lola, such as the pornographic images that can now flicker on every computer screen, represents an exaggerated overly-sexualized image of women. Tuggle is the reality. One is artificial and mindless, the other human and imperfect. In the same struggle is Melanie truly wants a completely pure type of love, but believes falsely that through sex she will receive love. Deep down, TV wants the same thing but he is also driven by his primal urges. Of course, under the influence of alcohol, he is unable to keep those urges in check.

Somewhere, at a beach-front motel, Melanie is waiting for her date. Unexpectedly, the first boy she dated in Florida shows up instead. The picture fades to black, but when we see her again she is alone: seated on a disarrayed bed, wearing a torn dress, her hair and mack-up disheveled and smeared. She has been raped. She calls the hotel looking for Merritt. The women rush to her aid. But she does not wait for them. Instead she walks onto the freeway into open traffic. Just as Merritt and the others arrive, Melanie is struck by a car. In the hospital, Melanie, now filled with shame and regret, cries to Merritt, saying: “I feel so old.”

Melanie’s short stint as a sexually active young woman took its toll. Just as the hard looking Lola, she is no longer fresh-faced like Merritt. Her statement about feeling “old” reminds me of the increasingly haggard looking Lindsay Lohan who looks middle-aged. In the same boat is Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera who popped on to the scene as precocious teens then lost their youthfulness incredibly fast. Here, Melanie is also drawing a parallel to the worn-out and overly experienced Lola. Interestingly, Lola’s look in the film: dyed blond hair, heavy eye makeup and lipstick combined with an unmistakable carelessness, is the personae still most adopted by female porn-stars. But for woman, the affairs of the heart can be devastating. Men tend to rebound very quickly. I find this difference to be mainly biological. Women are designed to internalize, nurture, and comfort. Men are made for the hunt, fight and flight. As all too many welfare mothers know, women are often left with the results of indiscriminate love-making while the men seek out other conquests. In an age when women are no longer protected by their family, they must rely upon their own skills of survival.

After viewing WTBA, and I have watched it several times, I find myself left with a feeling of sadness but also one of hope. Sadness, because we watch helplessly as Melanie makes one mistake after another that eventually leads to violence. Though I certainly do not blame Melanie for her rape, no woman chooses to be violated, she did place herself repeatedly in dangerous situations. Here we see how it is that many women have been duped into a false sense of security. Casual dating puts women at risk. In Melanie’s case, she admired and emulated far too much her inflated and somewhat romanticized image of the liberated women, represented by Merritt, who could find her own soul-mate through sex. But is the man who sleeps with a you (or wants to sleep with you) on the first date, the man who will marry you? And with this independence came a false idea of sexual equality. As Melanie found out, women are still at a distinct physical disadvantage. She fought her attacker, but lost. The tragedy of her lost youth has been repeated over and over again since the 1960s. But herein also lies the hope of the film.

The last shot of WTBA, finds Merritt alone on a beautiful but deserted beach. The sand is clean and white, no longer covered with sun-burnt half dressed bodies. She is alone and deep in the world of her own thoughts. Ryder suddenly appears. Previously, at the hospital, she blamed him and all men for treating women as sexual playthings. The heat of her emotions, from the previous day, have now cooled. They talk, then share a sweet kiss. They have agreed to approach their relationship slowly and get to know each other. Earlier, Tuggle and TV came to a similar resolution. And this is the hope. Not a return to chaperones and chastity belts, but an acceptance of Man’s limitations. We are sexual beings and subject to the yearnings of the flesh. But we also have a soul that can transcend our earthly concupiscence. Especially in the young, free reign must never be given to our bodies. And in today’s youth culture this is exactly what has happened. We saw it’s beginning in WTBA. Now, we must all live with the human costs: abortion, sexually-transmitted diseases, and bitter and angry youths who find themselves missing their lost childhood.

A movie is a movie and should be treated as such. The degrees of sexual activity — and consequences — are all very individual and depend on a range of factors. Comprehensive sex education has been shown to decrease unwanted pregnancies and STDs by giving students information they can use to cub risks associated with most behaviors. There are plenty of sexually active women who do not meet the defeated, “haggard” looking description used by the author. In reality, drugs, cigarettes and alcohol are the culprits in accelerating aging for the likes of the entertainers mentioned and others. The main point is, there are many degrees of sexual activity and neither women, nor men, can be categorized as either “saints” or “sluts.”

Joseph- I really enjoyed your essay about WTBA. It resonated with me as I am a woman who has witnessed the damage that sexual activity without love and/or commitment has done to countless women, from family members and friends to acquaintances. I’ve watched from that sidelines due to being an observant Catholic. Any concerns I have expressed about the lifestyle choices being made were dismissed by most; some have told me later that they regretted not listening to me. “You can’t delete memories,” a good friend told me many years afterwards.

As to the previous commenter, I think that “John” doth protest too much. I’ve noticed that men are much more invested in the sexual revolution than women are, and find it easier to deny or minimize the damage caused by it- most likely, I think, because they reap many of the benefits, while women and children suffer most of the negative consequences. I laughed out loud when he wrote that WTBA was “just a movie.” Movies are of course a reflection of the norms and values of the culture that produces them. They are a form of audiovisual art, and as such can be analyzed like a painting would be. I wonder if John thinks that sex outside of marriage is “just sex.” It wouldn’t surprise me.

Comprehensive sex education has certainly not reduced STD rates. In fact. the CDC stated that they were at an all-time high in 2018! The CDC report on STDs that I have cited was released in October 2019, so we’ll have to wait until the fall of 2020 to see if 2019 was another record setting year.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2019/2018-STD-surveillance-report-press-release.html

As to teen pregnancies, the CDC postulates that abstinence and use of birth control are the main reasons for a lowered birth rate. https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm

I don’t think that teens should be having sex in the first place. Glad that some teenagers are starting to understand what a bad decision it is as well.

John seems to think that there is nothing wrong with premarital sex, and that any physical changes (looking haggard, accelerated aging) are due to ingesting illegal and/or heavily regulated substances, and not the result of sexual activity with multiple partners, many of which are actual strangers. I wish that was the case. It seems strange to say, but I think some people can become addicted, for the lack of a better word, to using others- it becomes a power trip of sorts, and is difficult to give up. From what I have observed, women who live such a sexually active lifestyle are changed by it, and not for the better. Their personalities become warped from using others and being used; the women (and men) in time become bitter and cynical. They turn to excessive drinking and drugs to cope with how they are living, and to disconnect from themselves and their actions. It is a sad thing to witness. I think the mental and psychological stress that they are under ages them. I pray that all women and men that have become victims to the lies that our culture tells about sexuality will be healed of the many wounds- physical, mental, and emotional- that they bear.