I was born in 1969; the same year that Pope Paul VI officially promulgated the Novus Ordo or the “New Mass.” Growing up in the Catholic Church during the 1970s and 80s, it was the only Liturgy I ever knew. The “Mass” was usually a rather demonstrative event; almost always accompanied by a strumming guitar – hence the so-called “guitar mass.” The Novus Ordo was supposed to look more accessible and interactive. At school, the nuns in short-skirts and tight turtle-neck sweaters taught us songs from Simon & Garfunkel which we sometimes sang at church. Later, our repertoire at school Masses was drawn almost exclusively from the songbook of the St. Louis Jesuits; a favorite of the children’s choir director was “Here I am Lord.” A song composed by the Jesuit priest Dan Schutte who later came-out as a homosexual. A bad omen of things to come.

My First Communion was not particularly memorable, except our teacher told us to always keep our hands together in front of us (palm to palm) when we approached the priest in order to receive the Eucharist. To ensure our compliance, she placed a small piece of paper between our hands and told us to keep it there. I was terrified of dropping it. The following year, a priest heard my first Confession. Back then, they still took place in the old confessionals where the priest was separated from the penitent by a wall with a screen. I didn’t really know what I confessed, but it wasn’t much. I was about 8 years old. I was just nervous as a tried to remember the set of prayers I was required to recite. Our teacher had drilled us for months: “Forgive me father for I have sinned…” But this was an odd time immediately following the institution of the Novus Ordo when some old ideas and methods (and parochial school teachers) still persisted; with a focus on memorization as the singular form of catechism. A year later, we were told to receive Communion solely in the hand; what was once forbidden became mandatory. A related matter: in 1973, the American Psychiatric Association declared that homosexuality was no longer a mental disorder; they had no scientific reason for making this pronouncement – they just did it.

When my parents took me to church on Sundays, I don’t remember much; except I often imagined myself being anywhere else. But, overall, I was a bit of dreamer. As a child, I was prone to being a loner – more comfortable drawing pictures in a sketch-book than playing ball with other boys. I always felt like an outsider. Then, one day, a priest followed me to the boy’s lavatory. Where he molested me. After that, I started to isolate myself even further. As a result, the other boys thought I was totally odd. They began to mercilessly tease me. Oftentimes, they called me gay. I did not even know what that meant.

In middle-school, I briefly served as an altar boy. For a short time, under the strict jurisdiction of a rather stern and imposing pastor, I experienced some form of comradery with other boys. But within a year, a new (more gregarious) pastor arrived and he welcomed female lectors and acolytes who took over. One by one, the other boys left. Until I was the only boy there.

At school, I had few friends. When I went into high school, I almost had none. I was introspective and lonely. By then, I knew what gay was. And I thought – that’s me. I was desperate for male affection from anyone. Then, the priest who molested me as a boy reappeared in my life. He was kind to me, at a time when very few were. Only, he made me nervous. But, one night, after an event at church, I got into a car with him. It was a dumb thing to do, but I was a damaged kid.

Over the following years, I rarely if ever entered a church again. When I left for college, I never really thought about what had transpired during those previous difficult years. I started over. I had a new life. I came-out as gay when it wasn’t cool to do so. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic. However, I had a plan. I wasn’t going to have sex. I only hoped for a few friends. Yet, when I arrived in San Francisco’s famous Castro District, I quickly discovered that the boy who no one wanted to be around was suddenly surrounded by men who wanted to be with me. They were always older. Suddenly, my initial plan was abandoned. But nothing ever lasted very long – not even long enough to form a friendship.

As I got to know more and more gay men, strangely enough, I slowly learned that a number of them were raised Catholic. Almost every one of them had a bizarre story about a predatory priest or religious brother. I remember a particular guy who told me about a sadistic Christian Brother at his school who forced some of the boys to perform calisthenics in front of him while they were naked. In retrospect, the sharing if these traumatic events in such an informal manner (sometimes bordering on the comedic) was sort of a group trauma session where unfortunately the abuse became normalized because such memories were common to nearly everyone. Its not surprising that there’s a persistent problem of mental illness in the LGBT community. In a sense, the Castro became a large open-air mental ward where no receives proper treatment.

A few blocks from the gay hub of Castro Street was a Catholic parish – Most Holy Redeemer. The place had a reputation in the area as gay-accepting; it was also the home to a ministry which helped those who were suffering with AIDS. I tended to avoid even walking by it. Except, a friend of mine asked me to be a guest at his “wedding.” The ceremony could not take place at the church, but the Catholic priest would officiate at the couple’s house – followed by a backyard reception. Afterwards, I briefly stood near the priest when some of the other guests were gathered around him. I overheard his philosophy about homosexuality, AIDS, and the Catholic Church. He believed that gay men must embrace monogamy. I laughed to myself. Then, I’ll never forget what he said: “I would rather marry them, than bury them.” He thought that by pronouncing some magic words over this couple would change their disordered orientation. That he had the power to change nature. This sort of word fixation in Catholicism is most commonly associated with its subsect of Protestantism and their obsession with Sola Scriptura; but persists into contemporary Catholicism when its adherents minutely dissect every word uttered by the Pope – even when he is making off-the-cuff remarks on an airplane. I lost touch with my newly married friends. A few years later, I heard that one of them had died of AIDS.

After almost a decade, my life as a gay man started to unravel. I lost faith in the promises of sexual freedom and expression. I started to haunt the Castro Theater where I endlessly watched double-features of old movie that usually featured the “gay icons” of old Hollywood: Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe, and James Dean. Lacking a sort of state-sponsored religion, gay men created one of their own; hence their collective obsession with film and pop stars who sometimes tragic lives created a gay hagiography. But these “icons” had no power to heal or intercede on anyone’s behalf. For a while, I thought I’d try settling down with one partner – maybe that priest was right, I thought. Yet, it never worked out. At that point, I met someone who I began to confide in. I told him a lot. At first, he was kind and gentle until I discovered that he was also a Catholic priest. Our relationship subsequently became sadistic and abusive. I submitted. I think I had given up. What followed were several vain and pathetic (albeit imaginative) attempts to kill myself. I finally found myself face down on the sidewalk. I was alone.

Looking back, I cannot explain why I chose to return to Roman Catholicism. I didn’t want to do it, but I knew one thing – it was Jesus Christ who had saved me. And I thought I could only find Him in the Catholic Church. I went back to what I knew. In San Francisco, there were certain doctors who treated the “special” problems unique to gay men; they were good at temporary repairs, but they certainly didn’t practice preventative medicine. And that was the Catholic Church. I’ve often thought about this question and I’ve come to the conclusion that childhood abuse victims will sometimes try to repeat the abuse in adulthood in order to make it seem not as bad. In fact, half of those who experienced childhood sexual abuse will be re-victimized as adults. Amongst women, this can be especially pronounced with those who become promiscuous as adults. Of course, in the gay male community, rates of childhood sexual abuse are astronomically high.

In Roman Catholicism, there is an underlying philosophy that honors extreme forms of subjection and maltreatment. This is evident in the practice of self-flagellation during the Medieval period and the often-grotesque depictions of a beaten, bloodied, and crucified Christ in Catholic art. As things got worse and worse for me in the Catholic Church, I sometimes believed I deserved it or the abuse was necessary for my own salvation. In Roman Catholicism, there are some strange precedents set in terms of self-harm: St. Jeanne de Valois and St. Margaret Mary Alacoque were known to have cut or injured themselves while St. Benedict and Francis of Assisi would roll about naked in thorn bushes.

After deciding to return to Roman Catholicism, I immediately sought out a priest I’d met many years before in the course of a home visit with my parents during some holiday; maybe Christmas or Easter, I went to church with them, hated every moment of it, but this young priest was different; he sounded honest. I looked him up; since then, he’d relocated to a nearby city. He remembered me. I was shocked. What followed was pretty simple: I went to Confession and received Communion for the first time in a couple of decades. It felt good. Only, I didn’t have peace. This priest was a good field medic – he got me up and most likely saved my life. But the benefits never seemed to last very long.

At his parish rectory, the pastor lived with another man; a parish-employee. The priest I liked? He was living alone in a mobile-home park. Madness. I had just left that world and like a demonic spirt, it had followed me here. (Over the years, I learned that this was an endemic problem in Catholicism; as most parishes within walking-distance of gay neighborhoods like the Castro, Greenwich Village or Santa Monica were always dominated and controlled by homosexuals; perhaps a definitive example of the patients running the asylum.) Although he decisively leaned traditional, the Liturgies at the parish were a PTSD-inducing return to the folk Masses of my childhood. I couldn’t endure them. Almost immediately, due to his recommendation, I started attending the Traditional Latin Mass or TLM. Then, they were difficult to find: one at a rundown parish in Sacramento and another at a semi-underground location in San Francisco. It was as if the Church had returned to the catacombs. The Liturgy was a revelation; characterized by a methodical order and tranquility; with the low-Mass distinguished by long periods of silence. But there was something strangely clinical about the Mass; performed like a formula; this is reflected in their obsession with the 1962 Edition of the Roman Missal. In hindsight, the TLM is head-centered and trapped in a Thomas Aquinas mindset. While it was a welcomed respite from the cacophony and chaos of the Novus Ordo, yet it felt as artificial as the retro-1970s guitar Masses. The Latin Mass was something out of Brigadoon; hopelessly stuck in a mythical past that sometimes bore little resemblance to the historical truth. It often reminded me of a military reenactment group that got together and dressed in period costumes; particularly those dealing with the Confederacy. Like they were desperately clinging to a world that was literally gone with the wind. But it was more than that. The culture surrounding the Latin Mass was also a late-20th century vision of pre-Vatican II Catholicism that was highly influenced by the sorrow and destruction that the so-called reforms of the post-conciliar Church wrought upon the faithful. I remember speaking with an older woman who left the Church following the introduction of the New Mass; now, overjoyed, she had returned just in the past few years once the Latin Mass became available again in her hometown. A priest, who lived through the rupture caused by the Vatican’s tinkering with the Liturgy, explained to me how he suffered through those years – and eventually retreated to a monastery where he still had to the celebrate the Novus Ordo, but was not forced to face the congregation and perform, what he referred to, as a sort of “pantomime.” The Church left behind traumatized people – as it had done before; for instance during the pogroms to rid itself of married priests – which set the groundwork for the Inquisition some 400 years later.

Only, I can not judge in hindsight those who longed for some utopian vision because I did as well. In fact, I wanted nothing more than to leave California and seclude myself in some faraway hermitage. Instead, I met a group of priests (newly expatriated from the ultra-traditional Society of St. Pius X or SSPX) residing in Northeastern Pennsylvania who dreamed of establishing a medieval-style village surrounding a Latin Mass community of priests; they dubbed themselves the Society of St. John. As soon as I could pack what few things I had left, I moved across the country – as far away from San Francisco while still remaining in the United States.

At first, I was content. Almost totally isolated from the outside world; I had no access to television, computers, or the media; we had very few visitors. I was engulfed by the surrounding wilderness, with the nearest large city over an hour away by car. But I began to think – the devil has followed me once again; or maybe I was just slowly going insane. Because, I started to notice something strange. Occasionally, several young men would visit one or more of the priests who were in-residence; the superior-general of the order, seemed to foster what I found to be unusually close relationships with some of these boys. And because I worked in the kitchen of the main residence, I saw things that made me uncomfortable. By then I had a primary spiritual director and confessor, so I shared with him my concerns. Since he knew much of my past and background, he proceeded to use it against me. He said I had no reason to be alarmed. Nothing unusual was happening. According to him, I had projected the experiences of my past abuse onto this innocent priest whom I suspected of wrong-doing. I believed him. What followed where torturous months of self-doubt and self-recrimination. I had to distrust everything I saw. I was driving myself mad. Little did I know, my spiritual director was an abuser too.

Trying to escape the imprisonment of my own mind, I fled to the Benedictine Monastery at Fontgombault in France. I fled what I fled to. Once I got there, I didn’t want to leave. Ever. The place was magical; as if I traveled through time. At UC Berkeley, during my undergraduate studies, I became fascinated with Romanesque art and architecture; in 1989, I attended an exhibition of Byzantine iconography at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco. I was completely mesmerized. The icons were extraordinary, but the way in which they were displayed was exceptional. The galleries were dimly lit with oftentimes a single spot light illuminating each icon. They appeared to glow. Orthodox liturgical music played quietly in the background. Growing up in the deconstructed emptiness of post-Vatican II churches, this exhibition presented the sacred in a more profound way than anything I’d ever experienced in Catholicism. That day, perhaps my life could have gone in a very different direction. But I had no knowledge of the Orthodox Church; all I knew was Catholicism.

Footnote: Also in 1989, the pop-singer Madonna released her most significant album: “Like a Prayer.” The title song was a homage to the singer’s Italian-Catholic childhood when the Church was in a period of upheaval. In the controversial music video, Madonna made reference to the polychrome statues of the saints, shrines, holy cards, rosaries, and over-sized crucifixes; everything that the post-conciliar Church attempted to banish. It was a return to a highly emotional form of Baroque Catholicism typified by primarily female mystics like Catherine of Siena, Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi, and Theresa of Avila. The erotic aspects of Madonna’s image and music from “Like A Prayer” where inherent in the writings from those women. Back then, perhaps some of that was a reaction against the head-centered scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas. Yet, it became over emotionally and eventually tipped over into mania; Madonna would recreate that hysteria . But the Roman Church has a history of misdiagnosing its own illness; in the Middle Ages, instead of understanding the rise in popular piety – it suppressed the Spiritual Franciscans; at the height of Renaissance corruption – the Church doubled-down on papal supremacy; and when faced with the onslaught of modernism, the Church succumbed with Vatican II.

But Madonna, like much of the West, had a propensity towards sacrilege. Because the history of Catholicism is characterized by a series of ruptures: 1054, 1517, and 1962 – afterwards there is this constant yearning for the transcendent that repeatedly settles for feeble replacements; for instance, the papacy itself; and modern Western man’s subsequent obsession with hallucinogenic drugs, the diversion of entertainment, and the proliferation of pornography. I had been enmeshed in all three just a few months prior. Then, seemingly overnight, I went from the bathhouses and gay dance-clubs of San Francisco and West Hollywood to a monastery on the other side of the world. What should have been an opportunity for healing only resulted in further aggravating my wounds – and causing new ones.

In Pennsylvania, nothing had changed. Once again, I started to tell myself that I was imagining things. Except, when a visiting young man inadvertently told me something – I immediately knew it was all true. I was not crazy. I returned to California. But my desire to remain in this imaginary realm proved difficult to overcome; hence, I understand why some will go to great lengths in order to protect it. But when I was on the plane – halfway across the continent – somewhere over the Rocky Mountains, I had a convulsion. Such was the depth of the terror I had imprisoned myself in. Only I hadn’t been set free, I was afraid. In California, I didn’t know what I would do.

To myself, I denied almost everything. Because I had bought into the narrative – that the sexual abuse of boys and young men in the Catholic Church had primarily been a post-Vatican II problem that was relegated to the most liberal sectors of the Novus Ordo. The infiltration of modernist theology and so-called progressive pastoral practices, combined with a heavy deconstruction of the Liturgy, was the ultimate cause of the abuse crisis. But none of that was true. Like the Catholic Church itself, the TLM movement misdiagnosed the sickness of Catholicism, because the decline of the Latin Liturgy was a symptom of the problem and not the problem itself. Its actually something much deeper and darker. Maybe it all goes back to the Council of Trent when the Catholic Church determined that the Sacraments are not affected by the disposition of the priest. In other words, he could be a devil-worshipper, or a sadistic child molester, but as long as he recited the correct words – all is well. Trent convened after the Protestant Reformation and failed to address the legitimate concerns that the schismatics raised about depravity and immorality in the priesthood. It was a legalistic response. Reminded me of a conversation I had with a Bishop following my return to California from Pennsylvania. I reported to him what transpired while I resided in his diocese; his response, that the priests in question had not “technically” broken their vow of celibacy. I thought, What? A Catholic priest can crawl into bed with a drunk teenager, and remain technically in good standing.

In fact, perhaps ever since married priests were forcibly removed from the Church in the West during the early Middle Ages, and the imposition of mandatory celibacy for clerics, the Latin Church had become an institution dominated by male homosexuals. Highly secretive in nature that demanded total obedience from its adherents. And, since TLM communities strongly adhere to more traditional Catholic institutional practices of submission, extreme reverential treatment of the priest, and the almost cultish need to protect their insular conclaves from any outside influence or contamination – I would argue, they are more prone to abuse and the subsequent cover-up of these crimes. In the recent past, several cases have come to light, including in the Fraternity of St. Peter, the Institute of Christ the King, and the SSPX. In all of those horrific cases, at least initially, a significant portion of the laity vehemently defended the accused. Incomprehensible. But I covered-up my own abuse because I didn’t want to damage the Church. More importantly, I covered-up my own abuse again because I didn’t want to damage the Latin Mass movement. So, I extolled the TLM as a bastion of normality and a fortress of safety. God forgive me.

Aware of my ongoing difficulties, a friend from the TLM introduced me to a well-known “exorcist” priest. He knew quite a bit about me. I told him how I’d been struggling for many years with the pervasive corruption in the Church. I knew too much; and it was driving me crazy. He thought I was possessed. I dropped my head down towards my chest and started to laugh. I said to myself: So, this is how it ends? The Church’s prescription for a priest sex abuse survivor is exorcism. He stood up and grabbed the back of my neck. I flashed-back to that day in the boy’s restroom when that priest crept-up behind me and put his hands on my shoulders. But, this time, I told him to stop.

Over the years, as I’ve spoken with many priest sex abuse survivors, what I found was a common denominator, not among the priest offenders, but between their victims. For the most part, the majority of survivors were once rather trusting and devout boys and young men who demonstrated a great respect and reverence for the Church and the priesthood. Consequently, the betrayal of that trust was enormously devastating. As I moved from the Novus Ordo to the TLM, and found predators in both worlds, I increasingly believed that my options were few to none. If I abandoned the TLM – where else could I go? I didn’t have an answer.

Meanwhile, I often though I was losing my mind. I knew that almost every priest I spoke with in the FSSP either knew what was taking place within the Society of St. John or at least had strong suspicions. But they remained silent. Speaking out would have damaged the Fraternity’s own reputation as the boys who were preyed upon by the St. John priests were either current students of St. Gregory’s Academy (a boy’s school they administered) or were former graduates. Although I continued to attend Mass at their parish, eventually I couldn’t stand to be around them anymore. The final outrage occurred when I witnessed one of the FSSP priests publicly humiliate an adult male parishioner. And he took it. Like that exorcist priest – in Roman Catholicism, sometimes their preferred remedy is cruelty.

As a result, I started to commute over an hour to an SSPX chapel. The priests were less pompous than the FSSP; maybe because they were much more aloof. But the otherworldly aspect that I found in Latin Mass communities in general was intensified here. Like being in the bubble-city from the movie “Logan’s Run.” Where you are protected from the elements and outside harm, but also susceptible to the influence of mind-control. Although the majority of the parishioners were kind people, I could discern the presence of group-think. To imagine the outside world as the sole source of evil and corruption, and to think that the TLM was impenetrable. I kept hearing: Those bad things only happened at the Novus Ordo. Really? Because there was a predator in their midst. But they wouldn’t see it; or they didn’t want to.

Next, I moved on to the Society of St. Pius the V (SSPV). This sedevacantist (empty chair) group claimed that there is currently no valid pope. But everything I fled from was just getting worse. One day, I showed-up for Sunday Mass, and unlike most of the parishioners; I didn’t get in line for Confession. A long-time parishioner (whom I since became friends with) asked me why. I told him that I had confessed a few days prior with another priest; a Novus Ordo priest. He said the Confession was invalid; the priest concurred. I’d had enough. Previously I thought it strange how these people traced detailed genealogies that outlined the history of a priest’s ordination; who ordained him; and who ordained the bishop; and so on. As I know all too well, if they remain untreated, the psychological ramifications of trauma will cause serious mental illness. And these poor people were traumatized – by the Catholic Church. This was paranoid hysteria. But, for months, it was becoming increasingly evident that everything was questionable outside of this small church. It was like something from “Alice in Wonderland;” with every successive portal that you pass through, the world got smaller and smaller – and more ominous.

Suddenly, the landscape in the Catholic Church changed considerably regarding the status of the TLM. Pope Benedict lifted certain restrictions and suddenly diocesan priests were offering the TLM. I started going to those Masses almost exclusively. They seemed less insular and cult-like. Probably because they existed at an otherwise Novus Ordo parish and didn’t surround themselves within a closed-off community. People tended to show-up for Mass and then go about their day. I liked that. I did the same. But I soon realized how fragile were these reprieves from the frivolity of the Novus Ordo and weirdness of the TLM communities. And a new bishop (or pope) could severally subject the TLM to his personal whims and prejudices; which eventually happened. I began to think: Why should one man have this much power? The Liturgy belongs to God, not him. And, then, I started to question everything. Especially my allegiance to an institution that sole purpose was its own self-preservation.

And in 2018, everything came crashing down. In a last-ditch effort to remain in the Catholic Church, I attended the National Courage Conference in Philadelphia. Since my initial re-conversion to Catholicism in 1999. I’d been intermittently involved in the Courage apostolate which endeavored to assist Catholic men and women with same-sex attraction who wanted to be chaste. Back at home in San Francisco, the location of the meetings – usually some backroom or basement, reminded me of the nondescript sites of the TLM. While I supported the objectives of Courage, over the years I started to oppose their methods. From my vantage-point, the emphasis of Courage on chastity and not the underlying causes of same-sex attraction was doomed to a cycle of recidivism. Wherein the person with same-sex attraction battles their desires, succumbs to them, then returns to Confession over-and-over again while making little to no progress. During the oppressively formulaic Courage meetings, when some poor soul recounted how he was repeatedly drawn to cruising locations throughout San Francisco, I thought we should delve deeper into the psychology of those longings. That never happened. But especially among young men in Roman Catholicism, this appeared to be an endemic problem with its roots in the policy of forced celibacy in the priesthood. Years before, I’d met a guy my age who would was discerning a vocation with the FSSP; knowing my history (which I had made rather public) he confided in me that he had an ongoing long-term problem with pornography. Consequently, due to embarrassment, he would jump around weekly to different priests who heard his confession. He thought the priesthood would resolve the issue. I advised caution. But to this day, I hope he never became a priest. Catholicism clung to repression and not healing. For this reason, the Vatican has maintained that only those seminarians with “deep-seated homosexual tendencies” should be barred from the priesthood. But all sin is deep-seated. All forms of cancer still have the potential to kill if left untreated. And I was untreated in the Roman Catholic Church.

At the Courage Conference, the focus of the event was the 100th birthday of its founder – Fr. John Harvey who died in 2010. I had met Fr. Harvey a few times and found him to be a kindhearted old man. However, the Conference itself fell during the peak of controversy regarding the Jesuit priest James Martin’s radical claims about homosexuality and how the Catholic Church should minister to LGBT people. Almost nothing was said about him. The Catholic Church was once again covering-up the misdeeds of one of its own. The sudden notoriety of Martin was also indicative of an ongoing problem in Catholicism that I first witnessed during that backyard “wedding” in the 1990s, but dates back to at least the 70s, and that’s priests who openly advocate for gay affirmation in the Church. As a Catholic, I tried to argue that it really didn’t matter what was written in the “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” because that was always the retort whenever I drew attention to the widespread phenomenon of LGBT “Pride” Masses in almost every major dioceses in the United States and throughout the West; the “Catechism” is not worth the paper it’s written on if priests flagrantly disregard it. In addition, the affectations, and demonstrations of “friendship” or “bonding” by many of the attending Courage members was something I personally found inappropriate. Sitting and listening to a speaker with your arm draped over another man’s shoulder; t-shirts emblazoned with the artwork of Keith Haring; maintaining that a gay identity is unproblematic – only the activity. Some of it reminded me of my visits to a couple of Catholic seminaries: the former FSSP seminary at Lake Wallenpaupack in Pennsylvania where one seminarian blatantly displayed too many stereotypically gay affectations; and at the Archdiocesan seminary of Los Angeles in Camarillo where a priest instructor was clearly gay and not adverse to displaying his favoritism towards certain seminarians. I thought I had discovered some sort of freakish aberration until I started readings some of the works of Peter Damian – written over 1000 years prior. What I witnessed was nothing new. It’s not surprising that Peter Damian was an early advocate for self-flagellation.

Following the Courage Conference, I immediately left and traveled to Northeastern Pennsylvania, very near where I once resided with the Society and St. John, in order to spend a few days at an Orthodox monastery. Like returning to the site of a murder. But a lot had changed in the almost 20 years since then. I was less naive, but psychologically I was worse off, because I often felt disassociated from reality; like I was merely observing my life from outside of it. Four years prior, I first seriously spoke with an Orthodox priest about leaving Catholicism. Except, I couldn’t. It was weird; I instinctively knew that Catholicism wasn’t working, but a placebo was better than nothing. Except, as a Catholic, I constantly felt as if I were simply going through the motions; especially during Mass. My mind certainly wasn’t there, and neither was my heart. It was somewhere else, and for the time being – that place was nowhere.

Then the Cardinal McCarrick scandal broke accompanied by a bombshell “letter” from Archbishop Vigano; a grand jury “report” from Pennsylvania revealed the depth of the depravity; and the Catholic Church in Germany began to “bless” gay couples. When I got back to California, from the Courage Conference, the news dropped about how Fr. John Harvey had argued for returning predator priests to ministry. I wasn’t surprised. Unbeknownst to me at the time, Fr. Harvey apparently allowed homosexual predator priests to take part in Courage meetings and functions. Because, when I joined the Courage online discussion (chat) group, I was almost immediately propositioned by a priest with a history of homosexual predation. A longtime associate of Fr. Harvey was the famous Fr. Benedict Groeschel. I had met Fr. Groeschel soon after going back to California from Pennsylvania in the year 2000. I briefly said something to him about the time I spent with the Society of St. John. He thought I had a problem. It was many years later when I first learned that Fr. Groeschel “evaluated” one of the predators from the Society of St. John; he apparently didn’t report any major issues. So far, I could just barely tolerate pretending to be a Roman Catholic; after that year, I couldn’t even do that. So, I just decided to remain at home. I set-up an icon corner and I was determined to worship Christ on my own. It didn’t work. I rarely if ever prayed. I fell into a deep pit of depression. In particular, on Sundays I felt lost. I missed getting up in the morning and going to church. For the rest of the week, it seemed like something fundamental was missing. As if I stopped eating. This emptiness was a peculiar kind of self-starvation.

“When conversion takes place, the process of revelation occurs in a very simple way – a person is in need, he suffers, and then somehow the other world opens up. The more you are in suffering and difficulties and are ‘desperate’ for God, the more He is going to come to your aid, reveal Who He is and show you the way out.” – Fr. Seraphim Rose

One Sunday, I just decided to go to an Orthodox church. The same church I visited a few years prior. I had spoken to the priest there; he sounded like a good man. But, repeatedly in the past, when I became desperate, I tended to make rather desperate decisions. I wondered if this was just another. However, I always liked the expression “leap of faith” that appears to have originated with the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. In one of my favorite novels, “The Brothers Karamazov,” the author, Fyodor Dostoevsky – a contemporary of Kierkegaard – wrestled with a similar concept of faith in the character of Ivan Karamazov. I think Ivan wants to believe, but he’s afraid to do so. Fear is something instilled in many who’ve been abused or experienced early childhood trauma; and, in my estimation, all the Karamazov brothers fit that profile. It’s scary to believe; and as its also clearly evident with Ivan, it’s frightening to allow yourself to love. These are intimately related ideas that are deeply connected to trust. Overcoming these fears is essential. So, I stood at the back of an Orthodox church on Sunday for 2 hours. I didn’t understand much of what transpired, but my experience with the Latin Mass made some of it look familiar. I didn’t have that rapturous response like my first time attending the TLM; because I wasn’t coming from the vacuousness of the Novus Ordo. But it was beautiful and inspiring – and I was permeated by a sense of peace. This was the space where the gulf between the head and the heart became non-existent. But was I ready to trust again? Absolutely not. Yet, I wanted to try. And that was a great move forward for me. Because Orthodoxy spoke to my heart – reawakening the frozen nous I never knew I had. In my limited understanding, the nous is our ability to know and love God; it’s the indwelling of the “image of God” within us. When we become sick through sin – everything begins to break down: our body, mind, and spirit. As I’ve struggled to accept through my own almost life-long battle with mental illness, only a holistic approach which recognizes that physical ailments, psychological instability, and the sickness of the soul is deeply interconnected. Treating one – and not the others – is doomed to failure.

Since leaving the Catholic Church, I hadn’t received Communion or gone to Confession for about five years. I longed to go back. And I could describe this longing as a sort of spiritual hunger. Its like nothing I’ve ever endured. So, I greeted the day of my Baptism into Orthodoxy with anticipation and apprehension. On that morning, I was a physical and emotional wreck; I was quite ashamed of myself. My body wanted to convulse, but I wouldn’t let it. The demons were making a final stand – attempting to control my body. However, beforehand, the priest sat down with me and tried to comfort me – as a father would. Footnote: The idea of the “spiritual father” has been almost completely lost in the West, with the “spiritual director” taking its place; by way of the priest as a sort of facilitator. Fr. Gabriel Bunge, a former Roman Catholic and Benedictine monk who converted to Orthodoxy, wrote that “the spiritual father is both physician and teacher in one according to the example of Christ.” The Catholic example is more of a technician. This is clearly evident in the TLM with its paranoid and myopic focus on the priest as formula reader.

Since then, like with everything else in this earthly existence, I’ve struggled. I’m still guarded and tend towards self-isolation. I’m reticent to trust – anyone. Outside of the Catholic Church, I’ve sort of found my voice. As a Roman Catholic, I constantly self-regulated and self-censored my speech; which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Only, I suppressed and concealed anything which might negatively impact the Church, in particular the TLM. With those self-imposed restrictions gone, I spoke freely – perhaps at times too freely. But I had a lot to say. And I said it. Only, afterwards, it didn’t really make me feel any better. I’m oftentimes angry. I’ve become that strange kid again; the one who got picked on. I don’t like that person. I find him difficult to be around; as do my friends. He never really healed. And that’s a long and difficult process. In Roman Catholicism, not due to the institution itself, or even its teachings, but owing to the caring and compassion of a few good priests – at times, I did begin to recover; only to have those old wounds ripped open by those who were neither caring nor compassionate. And here, even my memories of those good priest are painful, because things did not conclude well for any of them. And their often tragic ends still haunt me to this day. Yet, I am still thankful for their efforts.

And herein is the ultimate reason why I converted to Orthodoxy – because the healing of my soul was impossible in the Church of Rome. Roman Catholicism only offered submission. Imagine undergoing surgery at a certain hospital – and something goes wrong. Later, you discover that the surgeon who operated on you had a history of malpractice complaints, but the hospital administration covered it up. But you return to the same hospital for help and answers; you undergo a corrective surgery which is also botched. Now, the hospital administration and staff say that you can’t go anywhere else. That was my situation in the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church de-frocked some low-level clerics, the equivalent of firing the janitor in a hospital that is rife with patient deaths and gross negligence.

But a pervasive claim in the TLM is that the Latin Mass embodies the “true” Church while the Novus Ordo is some “false” simulacrum. That argument goes so far as to contend that no one was abused in the Roman Catholic Church; only in the false Church. It’s a weird form of schizophrenia; they can’t come to terms with the fact that something went very wrong with Catholicism; going back to 1054 AD. The Catholic Church altered the Creed, debased the Liturgy, and butchered the children. Those who believe they can change the words in Christianity’s ultimate statement of belief, will one day think they cab do almost anything.

In Roman Catholicism, there are several examples (almost all clerics or religious brothers and sisters) who experienced persecution and abuse from within their own Church and still decided to stay; with St. John of the Cross, who was beaten and imprisoned by his own fellow Carmelites, as perhaps the ultimate example. Sometimes these stories are used against those Catholics who contemplate leaving the Church. I was repeatedly told: “You must stay in the Church and embrace your suffering.” A return to medieval self-flagellation. For a while I did just that. Until I was driven to suicide. But in Orthodoxy, St. John of Kronstadt takes a more balanced and healthy approach to this issue:

True love willingly bears privations, troubles, and labours; endures offences, humiliations, defects, sins, and injustices, if they do not harm others; bears patiently and meekly with the baseness and malice of others, leaving judgement to the all-seeing God, the righteous Judge, and praying that He may teach those who are darkened by senseless passions.

A significant line in that quotation: “…if they do not harm others.” Reminds me of the basic “oath” taken by doctors before they begin to treat patients; do no harm. In other words, if you so wish, willingly submit to every ordeal, if innocent bystanders are not abused in the process. St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco endured persecution from without and within Russian Orthodoxy. But he took upon himself all those slings and arrows; not for his own glorification, but ultimately for the welfare of those who were placed under his care as Bishop. That is true selflessness. The price of sanctity or sainthood in any religion should never require ignoring, tolerating, or enabling the abuse of others.

Now, I have hope. In Roman Catholicism, I had resignation – to my fate as a compliant, obedient, and wholly neglected patient in some nightmarish insane asylum – the church of Nurse Ratched; where you are beaten and manipulated into submission. St. John Chrysostom stated that “the Church is a hospital, and not a courtroom, for souls.” After spending a near lifetime in Catholicism, I realized that the Church of Rome is truly a courtroom – obsessed with legalism and procedures – manifesting itself in the 21st century with the Church’s manipulation of the Western legal system; primarily through bankruptcy courts, in order to force the renegotiation of settlement deals with priest sex abuse victims. This is perhaps part of the Roman Church’s legacy of Scholasticism that often makes it seem like a law firm. But this attitude is foundation to Catholicism; Fr. Seraphim Rose stated: “Their theology comes from human wisdom, not Divine revelation and Divine vision.” I finally realized that the supposed cure – the Roman Catholic Church – was making me sick.

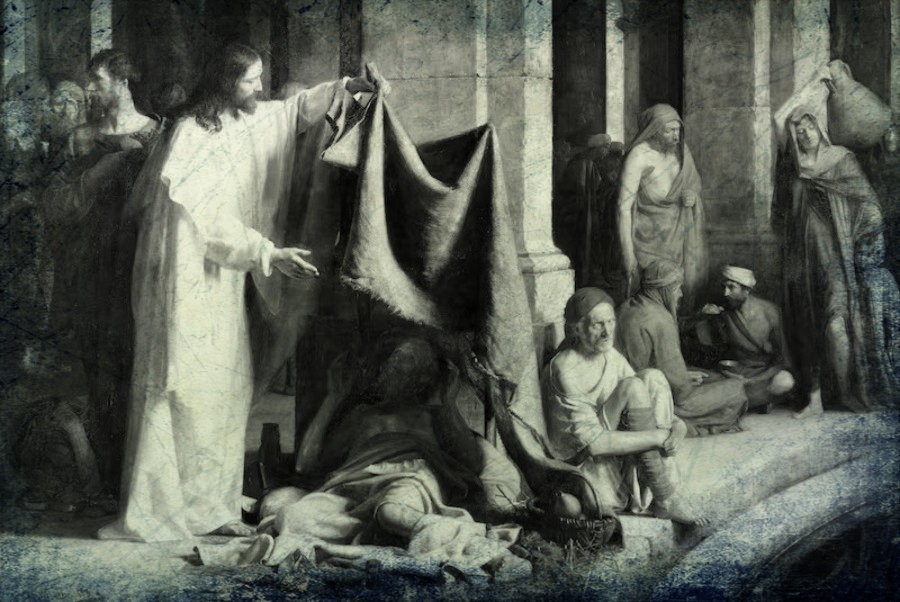

In Orthodoxy, I found those who were willing to suffer along with me; because there isn’t much they could say to me especially considering that they had nothing personally or institutionally to do with my past experiences of abuse and betrayal. Not everyone has, but its enough. And for that, I am truly thankful. It’s like becoming the paralyzed man who was lowered through the roof of a house where Christ was preaching. Because individual healing almost always involved a group-effort. I contrast this willingness to help me carry my cross with the Catholic bishops I met with who couldn’t even muster an apology. Because, to do so, would undermine the entire Roman Catholic project. And in the TLM, this suffering wasn’t even for the Church as it currently existed, but for some imagined vision of how Roman Catholicism once was – and could be again. Yet, it would be ungrateful to contend that no one is the Roman Church reached-out to help; they were brave and compassionate laymen whom I can never thank enough. In some respects, I owe them my life; like the “Good Samaritan,” they cared for me when almost no one would. However, they could only do so much, because once I was well enough to travel – I had to make my own way. They could assist in the healing of my body, but they could not relive the torment in my soul. For that, I had to look elsewhere.

Turning to Orthodoxy for a remedy to what ails me hasn’t been easy. I am persistently distrustful, and as a Roman Catholic, I got accustomed to allaying my fears through verification of the written word; because the papal bureaucracy is a voluminous publisher of various documents, pronouncements, encyclicals, etc. In Catholicism, there is a weird sort of “trust the science” mentality that relies upon the stream of legal papers coming out of Rome; as a same-sex attracted Catholic – this was frustrating. As I walked around San Francisco, past a Catholic parish waving the rainbow-flag and advertising its upcoming “pride” Mass, what then-Cardinal Ratzinger wrote to the bishops about the “pastoral care” of homosexuals really didn’t matter. Within Orthodoxy, I discovered that many such directives are not explicitly written down. Because they are lived. During one of my first conversations with an Orthodox priest, I asked him: “Will a ‘pride’ flag ever hang on this church?” Of course, his answer was a resounding: “No!” Catholicism has paper, but Orthodoxy has faith. A prime example: Orthodoxy has been able to preserve the Liturgy, and Catholicism has not.

I’m endlessly thankful for the blessings that God has bestowed upon me. I should have been dead countless times – mostly due to my own negligence, stubbornness, and self-destructive character at the time. But when I did present myself to the Roman Catholic Church as a repentant sinner – I did so as an obedient and loyal follower of the Church. And, in my case, and with many others that I personally know of, the Church failed. Miserably. Now, some Catholics would argue that the Church did not fail me, only individuals within the Church did that. However, I am not playing those mind-games anymore. Like the hospital which knowingly employs and protects physicians who regularly butcher patients – there is something structurally wrong with such an institution.

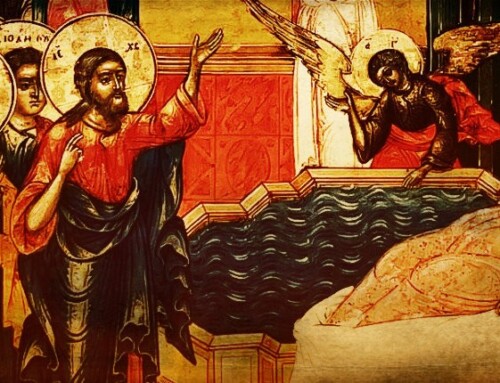

In Roman Catholicism, it was as if I were the hopeless paralytic by the Pool of Bethesda; if I had remained Catholic, I am sure I’d still be lying there: unable to move, and becoming complacent with my situation. For this reason, when Christ encountered this man, He asked him: “Wilt thou be made whole?” or “Do you want to be made well?” In 2018, when I decided to leave Roman Catholicism, it had been 38 years since I was first abused in the Church. Subsequently, I’d experimented with various forms of self-medication; including: pornography, homosexuality, and mind-altering drugs. Nothing worked. Because I didn’t even know that I was sick. Catholicism did not offer a treatment. I started to attend the Orthodox Liturgy during its most intense time – during Great Lent. Before Pascha, one Sunday is dedicated to the “prodigal Son” and another to St. Mary of Egypt. Two great sinners. After Pascha, one Sunday is dedicated to the healing of the “Blind Man” and another to the healing of the “Paralytic.” Immediately, I thought: Orthodoxy understand the human condition: our tendency to become lost, to repent, and then seek healing.

From a Homily of St. John Chrysostom:

Since this man who had been paralytic for thirty and eight years, and who saw each year others delivered, and himself bound by his disease, not even so fell back and despaired, though in truth not merely despondency for the past, but also hopelessness for the future, was sufficient to over-strain him. Hear now what he says, and learn the greatness of his sufferings. For when Christ had said “Wilt thou be made whole?” “Yea, Lord,” he saith, “but I have no man, when the water is troubled, to put me into the pool.” What can be more pitiable than these words? What is more sad than these circumstances? Seest thou a heart crushed through long sickness? Seest thou all violence subdued? He uttered no blasphemous word…nor did he say, “Art Thou come to make a mock and a jest of us, that Thou asketh whether I desire to be made whole?” but replied gently, and with great mildness, “Yea, Lord.”

Today, looking back at over two decades of an ultimately fruitless endeavor to be healed – I was trapped in a cycle of temporary recoveries followed by continuous reinjury. Now, I am reminded of another invalid from Holy Scripture – the woman with a hemorrhage who bled-out for 12 years. Such a condition is life draining; after getting out of the gay community, I couldn’t stop losing blood. I was slowly becoming anemic; I might have died. In Catholicism, I suffered from a sort of spiritual anemia. But the longer I remained, the more helpless I imagined myself. And this made me angry. According to Archbishop Averky of Syracuse:

“With His one word alone, the Lord healed an invalid who had lain for 38 years near a healing spring hoping in vain to be made well. And raising him up from his sick bed, He cautioned him respecting the future: ‘Sin no more, lest a worse thing come unto thee (John 5:14).’”

That is my struggle. Now, that I have found a route to healing, will I fall into an even more deadly sin? That of anger. I battle with it every single day of my life. Most of the time, I don’t tip over into the realm of hate; but not always. Over the years, I’ve spoken with and gotten to know over 100 priest sex abuse survivors. With only a couple of rare exceptions, they’ve all left the Catholic Church; and the majority of those no longer subscribe to any form of organized religion; a large number have completely lost their faith – in God. While I understand their reasons, but it still makes me sad. So much was taken away from them already. Throughout this often insane journey, I’ve tried to hold on to one thing – hope. I always hoped, like the doubtful Ivan from “The Brothers Karamazov,” who perhaps was the son most deeply affected by the corruption of his father, that one day all will be made right – even after spending a lifetime surrounded by perversion and cruelty. Ivan said this to his deeply religious brother Alyosha:

“I have a childlike conviction that the sufferings will be healed and smoothed over, that the whole offensive comedy of human contradiction will disappear like a pitiful mirage…feeble and puny as an atom, and that ultimately, at the world’s finale, in that moment of eternal harmony, there will occur and be revealed something so precious that it will suffice for all hearts, to allay all indignation, to redeem all human villainy, all bloodshed; it will suffice not only to make forgiveness possible, but also to justify everything that has happened with men.”